Highlights

- When men do more housework, fertility may rise, or it may fall, or it may not change at all. Post This

- In many countries, when men do more housework, fertility falls. Post This

- Pressuring men to help out more at home won’t boost fertility. But perceived unfairness in the home may influence fertility. Post This

Is fertility low because men don’t help out enough at home? A lot of people, including many scholars, have argued that the blame for low fertility can be placed on men, and specifically their unwillingness to do their fair share at home. This theory comes in various forms, from a relatively formalized sociological theory around an “incomplete gender revolution,” to more descriptive approaches in economics papers. But the common theme is: if men would just help out more at home, women would feel more able to incorporate family into their life plans, and fertility would rise.

You can see examples of the argument all over the place. Most recently, progressive pronatalist Darby Saxbe claimed that men “hold the key” to boosting birth rates.

But is she right?

First, it’s worth noting that data on housework is complicated. It can be measured by surveying people about specific chores they do, by asking them about the hours they spend on domestic work or about what work their spouse or partner does, or by using time diaries, or other methods. But the consistent theme in research on housework and fertility is that it is almost all cross-sectional. For example, a 2023 economics paper, despite being published just two years ago, has already been cited over 330 times, and shows a graph with a positive correlation between men’s share of chores vs. national fertility rates. In countries where men help out more, women, apparently, have more babies.

But there’s a problem with this theory. There are many reasons fertility or child care arrangements might vary. Do Swedish women have more babies because Swedish men do more housework? Or do Swedish men do more housework because Swedish women have more babies? Or is there some other fact about Swedish culture causing more babies and more men to do housework?

To start to untangle this, it’s crucial to look at change over time. How has housework changed? While there can be uncontrolled confounding in change-over-time too, it’s reasonable to think that, if men doing more housework causes higher fertility, then when men’s housework share rises, fertility should rise, too.

There are three datasets that can track changes in housework over time. First, in 1994, 2002, 2012, and 2022, the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) asked an identical set of questions about who did what chores. Four chores were consistently kept across all waves: laundry, cooking, caring for sick family, and grocery shopping. Second, the ISSP (in 2002, 2012, and 2022) asked respondents how many hours of domestic work they did. And finally, for several countries, time-diary data is available, which is the highest-quality data source on how individuals spend their time. For each of these, I assess what share of domestic work was performed by men, among coupled individuals ages 18-54, and then I compare that to fertility rates estimated by the United Nations.

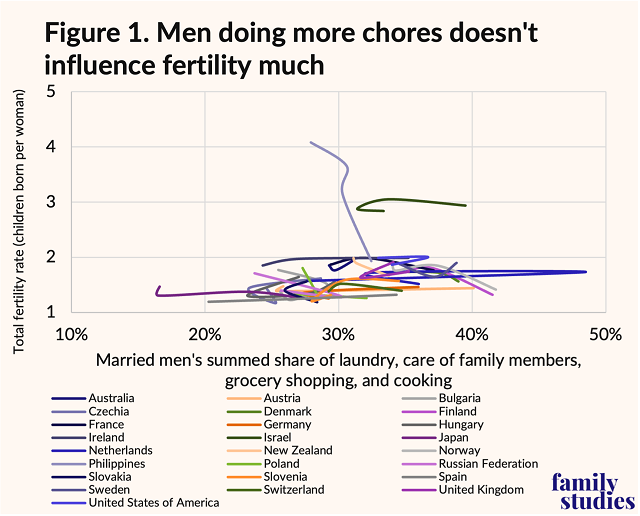

First, we can look at the chore-share data from the ISSP. The figure below plots the share of chores done by married men vs. country-level fertility, restricted to countries for which the ISSP has data in at least three periods.

Three things may stand out in the chart above. First, two countries in the sample have way higher fertility in general: Israel and the Philippines. Second, there are a lot of very jumbled lines on the graph, making it tricky to tell if there’s any relationship in the data. And third, maybe there are some lines sloping upward (i.e. more men doing chores yielding more babies), but it isn’t clear.

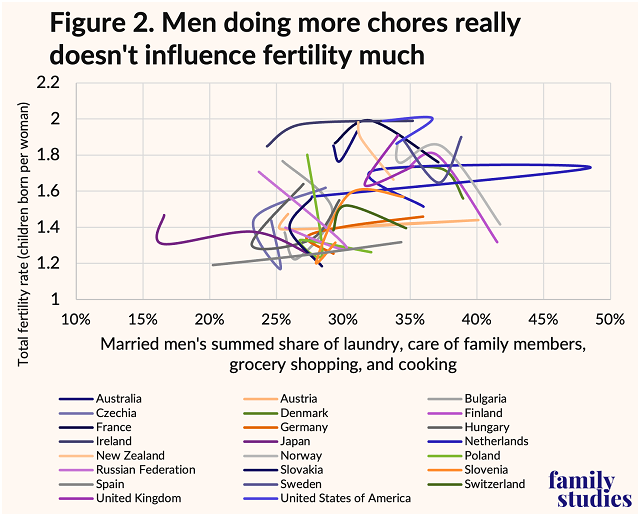

To make it easier to get a sense of the relationships, here’s the same chart, but now dropping Israel and the Philippines:

Zoomed in now, a couple facts are clear. First, the highest fertility countries actually have “moderate” levels of men’s housework: men’s housework shares above 35% are negatively related to fertility. Second, it is true that many very low fertility countries have very low rates of men helping out at home.

But third, and most importantly, there’s obviously no relationship over time within countries! Sure, some of the lines have an upward slope (like Spain in gray near the bottom, or the Netherlands in dark blue near the top right, Austria in a light orange in the middle, or Ireland in gray in the top middle). But in many countries, when men do more housework, fertility falls: Norway, Finland, Japan, New Zealand, Denmark, Bulgaria, and Russia have all clearly seen their fertility fall as men do more at home. In this data, when men do more chores, it just doesn’t really tell us much about what direction fertility will go. This is true as well if I specify a panel model with fixed effects: the coefficient on housework is near zero and not remotely significant. When men do more housework, fertility may rise, or it may fall, or it may not change at all. There’s just no relationship.

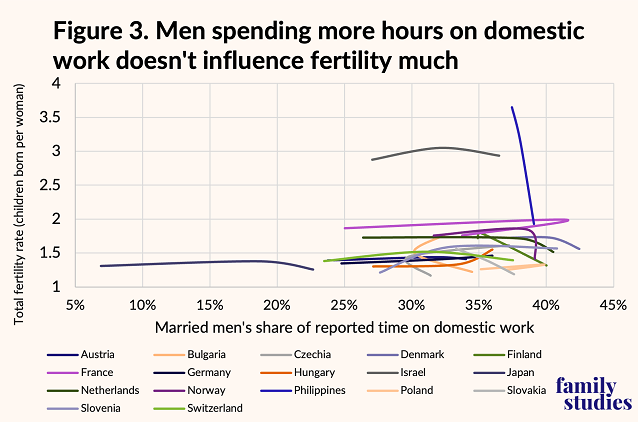

Next, we can do this same kind of analysis using reported hours of housework.

In terms of reported hours, the lines are not quite as noisy. And again, across countries, it looks like where men do more housework, fertility is higher. Compare Israel (top gray) or the Philippines (top right blue) to Japan (bottom left gray-blue).

But within countries over time, effects seem, again, inconsistent and probably near zero. Japanese men increased their housework share from 7% to 23% between 2002 and 2022. Fertility stayed about stable. Again, the expected positive relationship does emerge sometimes: Hungary (bright orange, bottom middle), France (bright purple, upper middle and right), and Germany (dark blue, bottom left) all have a positive slope. But other countries, like the Netherlands, Denmark, Slovakia, Finland, or the Philippines, have negative slopes. And for many countries it seems basically random. This tells us, again, that countries probably cannot boost their fertility by convincing men to help out more around the house.

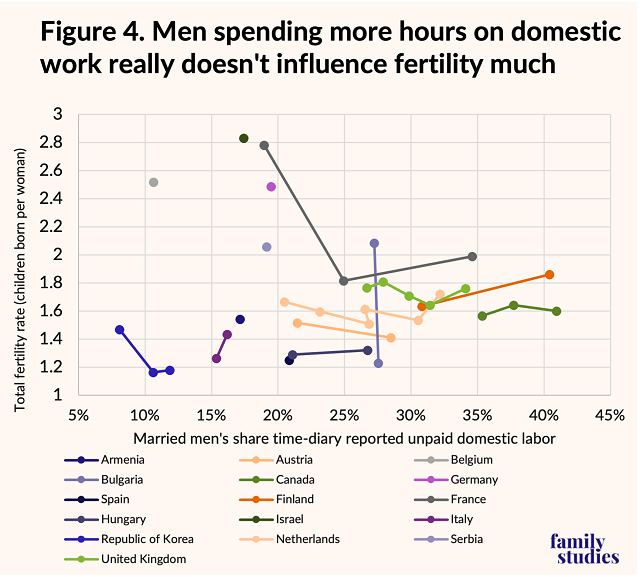

Finally, we can turn to time-diary data. Time diary data is probably the most reliable. The sample of countries with time-diary data for unpaid domestic work (queried using the Multinational Time Use Survey portal at IPUMS) is much smaller than the ISSP sample, with few countries surveyed repeatedly, so below I show the available data, including countries only observed a single time.

Once again, if you squint (and ignore the countries that were only sampled one time), you could perhaps convince yourself that in countries where men do more housework, fertility is higher: Canada (green at right) and Finland (orange at right) are much higher than Korea (bright blue bottom left) or Italy (dark purple bottom left).

But when we look within-country, the only country that seems to have a clear positive slope between men’s share of domestic work and fertility is Finland. When the men of a country step up and do more housework, there just isn’t a change in fertility.

Thus, the theory that fertility can be raised by men doing more housework is hard to believe. We’ve witnessed big changes in men’s housework in many countries! Fertility just doesn’t respond!

Now, this does not mean housework doesn’t matter. Maybe what matters is the total volume of housework. In time-diary data, married American women report 150-180 minutes per day of unpaid domestic labor. Dutch women report 200, which is similar to Korean women. Italian women report almost 300, while Hungarian women report 240. Armenian women report just 150 minutes. It’s possible that there could be large variations in cultural expectations about the total amount of work to be done that influence fertility regardless of the gendered division of that work. It’s also easy to imagine that there might be variation in the other demands placed on spouses: countries vary a lot in workplace culture, care responsibilities for older parents, and preferred forms of leisure. This could all lead to “objective” measures of housework sharing being a very poor match for the “subjective experience” of having a bad division of labor at home.

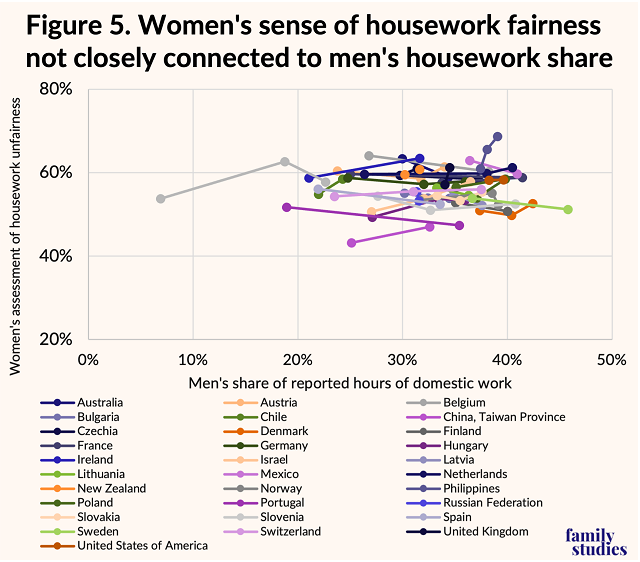

The ISSP allows us to test this latter theory! The ISSP asked people if they felt they were doing more or less than their fair share of the housework. The correlation is shockingly weak, as shown below:

In countries where men do more housework (further to the right on the graph), there is basically no big difference in women’s views of whether the division of labor at home is unfair (further up the graph means more unfair housework division). By the way, this is true for men too: there’s basically no relationship between either sex’s view of if they’re being treated fairly, and how much housework the other sex does. The simple fact of the matter is that, at the aggregated, societal level, opinions of the fairness of housework distribution just have very little to do with the actual housework distribution, and a lot to do with other cultural factors, other public narratives about gender, and other stresses and tensions on couples.

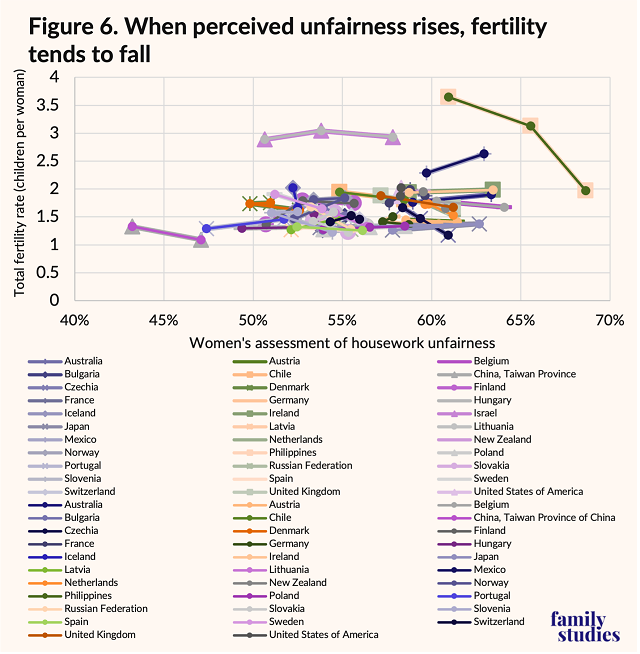

But this then brings us to a key place where scholars focused on housework just might have a good point: while objective housework distributions don’t matter very much for fertility or for partners’ sense of fairness, subjective views of housework distributions may still matter! The figure below plots women’s assessment of unfairness vs. TFR.

On the one hand, across countries, fertility is highest when women say housework is the most unfair. But that’s just the cross-sectional relationship: within countries, most of the observed relationships are negatively-sloped or neutral: as women feel housework is becoming more unfair, fertility falls. Whereas all the measures of men’s housework shares had small and statistically insignificant effects on fertility in panel models of change over time, women’s sense of unfairness in the home has a fairly large observed effect and is around the threshold for statistical significance (the small sample size in this case makes it difficult to produce any highly robust results).

The takeaway from all of this is simple: pressuring men to help out more at home won’t boost fertility. But perceived unfairness in the home may influence fertility. The central intuition that when women feel their burden at home is unfair, they have fewer children is true. But unfair home burdens don’t really have much to do with the amount of work men do at home, and may have a lot more to do with other demands on men and women’s time, or broader social and cultural narratives.

For fertility to rise, what countries need is not for one sex or the other to juggle their duties differently, but for society at large to take some of the balls out of the air so they simple don’t have to juggle as much, and also for cultural narratives to push back against framing of family life as an arena of power dynamics, competition, and gendered struggle. How much help women get at home doesn’t impact society-wide judgments of fairness. But how much society around them preaches that men are sexist might.

Lyman Stone is Senior Fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.