Highlights

The standard portrayals of economic life for ordinary American families paint a picture of stagnancy, even decline, amidst rising economic inequality. But rarely does the public conversation about our changing economy, from the pages of the New York Times to the halls of the Brookings Institution, focus on questions of family structure. This is a major oversight: though few realize it, the retreat from marriage plays a central role in the changing economic landscape of American families, in race relations in America, and in the deteriorating fortunes of poor boys. In a word, the increasingly “separate and unequal” character of family life in the United States is fueling economic, racial, and gender inequality.

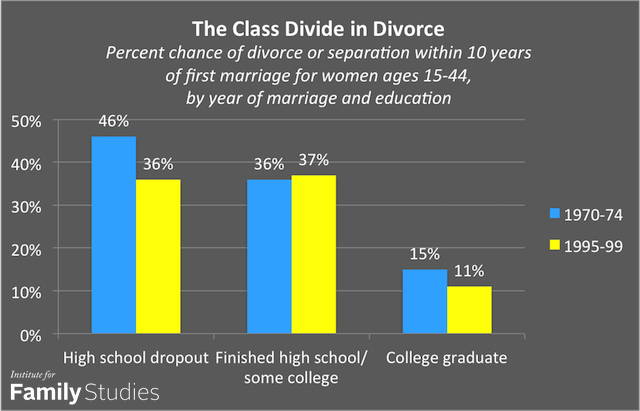

How is family life “separate and unequal”? First, Americans exhibit a growing class divide in marriage where the college-educated are more likely to enjoy high-quality, stable marriages than the less-educated. For instance, since the divorce revolution of the 1970s, divorce has fallen among college-educated Americans, while remaining comparatively common among Americans without college degrees.

Source: W. Bradford Wilcox, “When Marriage Disappears: The Retreat from Marriage in Middle America” (Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project and Institute for American Values, 2010).

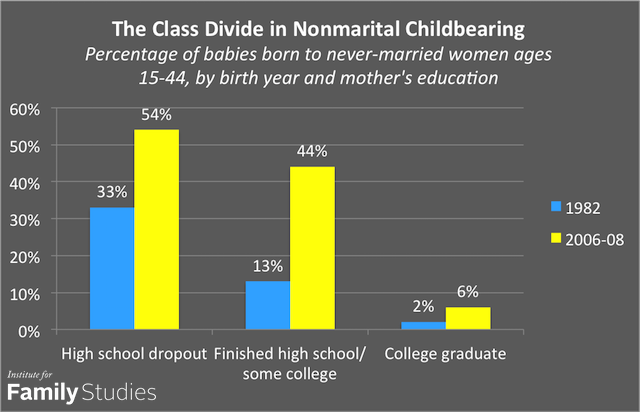

A similar gap is evident when it comes to childbearing out of wedlock. About half of babies born to working-class and poor Americans are born outside of marriage today, but just a small fraction of babies born to the college-educated.

Source: Wilcox, “When Marriage Disappears.”.

The class divide in family life is concerning for many reasons, but chiefly because it imperils the well-being of lower-income children, who are increasingly likely to grow up outside of a married home.

That family life has become more fragile and that economic inequality has become more extreme are not in dispute. Controversy continues, however, over which trend drove the other one—a question with implications for how we address the problems the two phenomena create.

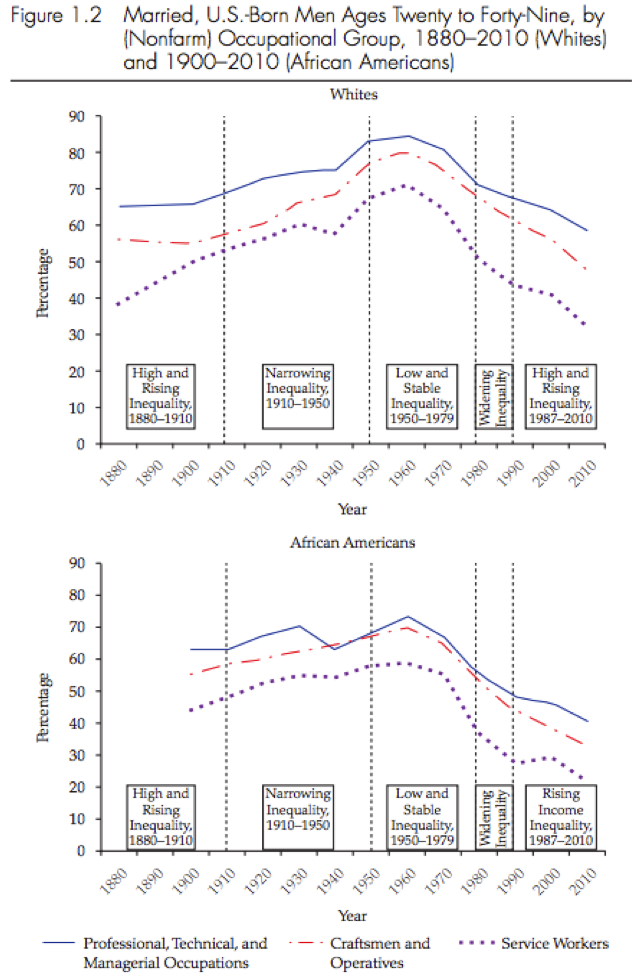

Looking at the timing of these trends, there is strong evidence that family change preceded growing economic inequality. Specifically, the rise of nonmarital childbearing and divorce date back to the 1960s, well before economic inequality began growing in the late 1970s. One clear illustration of this fact is a figure from Andrew Cherlin’s book Labor’s Love Lost, reproduced below, showing the changing prevalence of marriage among prime-age, U.S.-born white and black men over the past century. For both groups, marriage began declining during a period of “low and stable inequality.”

To underline the point: the temporal ordering of these events is more consistent with the idea that the retreat from marriage helped to fuel the upsurge in income inequality in America than vice versa.

Was the timing of these trends purely coincidental? We believe the answer to this question is no. As we’ll show below, scholarly research demonstrates that America’s growing marriage divide has helped to fuel three forms of economic and social inequality.

First and foremost is inequality in Americans’ family income, which has risen since the 1970s. Various scholars such as Bruce Western at Harvard and Molly Martin at Penn State have concluded that between 20 and 40 percent of the growth in family income inequality is associated with the retreat from marriage: the rise of divorce and of nonmarital childbearing, which leave many children in homes with only one potential income earner. (It’s important to note here that the biggest contribution of family change to economic inequality came from the early 1970s to the mid-1990s, when family change was most rapid.)

The retreat from marriage also looms large in another form of economic inequality in America: racial inequality. Sociologist Deirdre Bloome has noted that in 1968, “just following the height of the civil rights struggle and the year of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, African American families’ median income was 60 percent as large as white families’ median income. In 2008, it remained 60 percent as large.” The racial gap in individual income, however, narrowed during that period. The explanation for that paradox: single parenthood grew faster among blacks than among whites amid the family revolution of the last half century. In Bloome’s words, “[racial] inequality might have declined further if the prevalence of single-parent families had not risen especially quickly among African Americans. Demographic trends may have slowed progress toward racial equality.”

Third, the growing marriage divide is fueling a historically unusual type of gender inequality in low-income communities, as the work of MIT economist David Autor shows. In a report called Wayward Sons and in new empirical research based in Florida, Autor and his colleagues explain that poor boys have been particularly hard hit by family breakdown in recent years. He discovered, for example, that poor boys from fatherless homes in Florida are much more likely to be absent from school than are poor girls from homes without fathers. The fallout of fatherlessness has also hit poor boys harder than poor girls when it comes to school failure, violence, and incarceration.

Why does marriage continue to make such a difference for families in contemporary America? It’s mainly because marriage is still more conducive to stable long-term unions than the alternatives. That means married families are more likely to pool incomes, create economies of scale, and avoid the economic challenges associated with supporting children across multiple households.

Children of married parents, in turn, benefit not just from these economic assets, but also from consistently having the time, attention, advice, and emotional support of two adults, not just one. Thanks to such factors, children of married parents are more likely than children of single parents to do well in school, avoid incarceration and teen pregnancy, and succeed in today’s competitive job market.

A lesser-known economic advantage of marriage relates to how it affects men. Economist George Akerlof, a Nobel laureate and husband to Fed chair Janet Yellen, has observed that “Men settle down when they get married: If they fail to get married, they fail to settle down.” That might seem archaic and out of touch, and it’s not true in every case. But even today, many men are transformed by marriage in ways that make them significantly more successful in the labor market. That may be most evident in the income gap between bachelors and married men. Even after controlling for a range of factors, from education to race to a measure of intelligence, married men earn about $16,000 more per year on average than their single counterparts.

Putting all this together, college-educated parents and their kids are flourishing not only because of educational advantages, but also because the parents are more likely to be stably married. Less-educated parents are struggling economically not only because they face a tougher labor market, but also because their romantic relationships and marriages are more fragile—and they and their children are doubly disadvantaged as a result.

But why did a marriage divide emerge in the first place? The left has a simple answer: money. Taking a page from the scholarship of William Julius Wilson, they emphasize that the shift away from an industrial economy towards an information economy has rendered less-educated men less “marriageable.” They’re not entirely wrong: The deteriorating economic fortunes of working-class and poor men do help to explain the development of the marriage divide, and if this problem is not addressed, it is unlikely that the marriage gap will close.

But economic shifts are by no means the whole story. Or in Brookings scholar Isabel Sawhill’s words, a “purely economic theory falls short as an explanation of the dramatic transformation of family life in the U.S. in recent decades.” There was no great uptick in family instability during the Great Depression, when economic dislocation and devastation were much more severe. And the academic research on family change in the last 50 years indicates that economic shifts only account for a minority of the retreat from marriage.

What explains the rest? At least three other factors also underlie the decline of marriage in the U.S.: culture, welfare policy, and civic change.

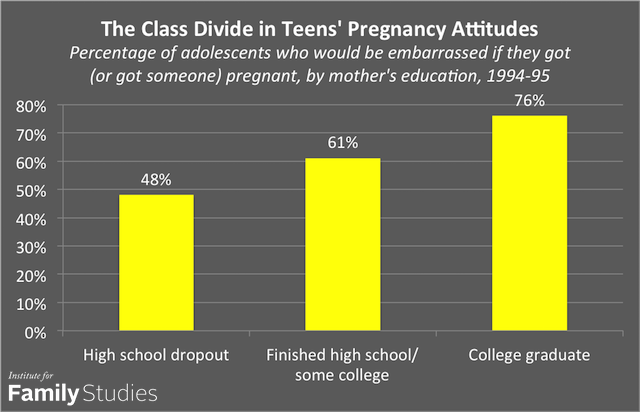

First, in the realm of culture, a more live-and-let-live relationship mentality has arisen that makes individuals much less likely to prioritize marriage. To be sure, the vast majority of Americans still want to get and stay married. Due to cultural changes stemming from individualism, feminism, and the sexual revolution, however, they have become much less committed to the beliefs and behaviors that make a stable marriage more likely. But these broad cultural shifts are now less evident among the college-educated when it comes to their specific orientation towards marriage. When it comes to their own lives, their own relationships, and their own kids, well-educated Americans are surprisingly marriage-minded. That is, they’re less likely to be accepting of divorce and to get divorced. To take another example, their teens get the message loud and clear that having a child as a teen isn’t acceptable, as the figure below indicates. And they act accordingly. The same is not true for adolescents from less-educated homes.

Source: Wilcox, “When Marriage Disappears.”.

Welfare policy also affects marriage trends. The literature suggests that changes in welfare policy—which have often made it easier for single mothers to get welfare and harder for married families to get such support—have contributed to the retreat from marriage among the poor. Welfare has not played as large a role here as many conservatives suspect, though. It’s just part of the story.

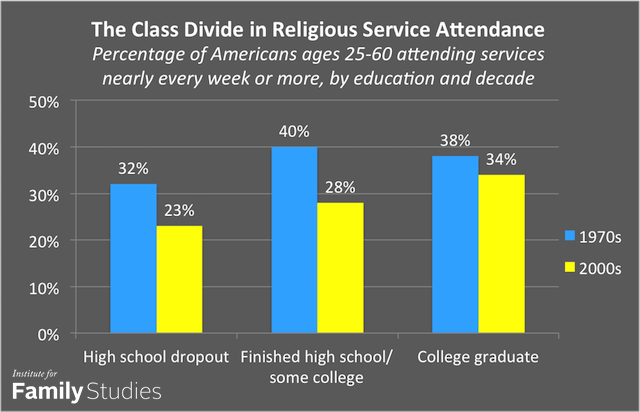

Third, the class-related marriage gap is related to the disengagement of less-educated Americans’ in particular from the institutions of civil society, including religion. One manifestation of this disengagement is in rates of weekly religious service attendance. Rates have declined across the board, but they have fallen more dramatically among those without four-year college degrees. That matters for family life because as many Americans can attest, even today, religious congregations supply married couples with important financial resources, moral direction, and social support.

Source: Wilcox, “When Marriage Disappears.”.

The bottom line is that the growing marriage divide is rooted in economic and non-economic changes that have undercut the financial, normative, and communal foundations of strong and stable families in poor and working-class communities. Given the many ways that marriages redound to the benefit of adults, children, and society, we should strive to reinforce these foundations in this century.

Some aren’t particularly optimistic about this project. Eduardo Porter of the New York Times says that “for the poor, marriage is over.” He thinks more generous welfare policies can effectively take the place of marriage. But even if we strengthen the safety net, making peace with the marriage divide means accepting a world where everyone but the college educated suffers the ills associated with family instability and where a high degree of economic inequality is locked in. This is a world that most people would deem unacceptable. And that’s why we should keep looking for new ways to revive the beleaguered fortunes of marriage among poor and working-class Americans.

This piece is based on remarks that W. Bradford Wilcox delivered at a debate in New York City on April 7 called “Money vs. Marriage: What’s driving growing inequality in the United States?” Full video of the debate is available here. The first paragraph is adapted from Robert I. Lerman and W. Bradford Wilcox, “For Richer, for Poorer: How Family Structures Economic Success in America” (Washington, DC: AEI and the Institute for Family Studies, 2014).