Highlights

In many major cities these days, homelessness is one of the policy challenges of highest public concern and controversy. During the last week of June, 70 different media outlets ran stories about San Francisco’s homelessness crisis in an effort to “provide [city officials] with the necessary information and potential options to put San Francisco on a better path.” New York mayor Bill de Blasio has taken a beating in the polls over perceived failings in his approach to homelessness.

There’s little debate among progressives about what the solution should be: more government-subsidized housing. But to what extent is homelessness purely a housing problem? A close analysis of New York City’s homelessness challenge shows that norms and family structure, not just economic pressures, shape the nature of the problem.

To begin with, city data plainly show that single-parent families are the largest driver of homelessness in New York. When most New Yorkers think of the homeless, they have in mind the desperate and/or disturbed man they pass by each day on their commute through Grand Central Terminal. In fact, members of families living in the shelter system maintained by the city’s Department of Homeless Services far surpass the number of single adults on the streets and in the shelters. Of the roughly 58,000 New Yorkers now living in a shelter, nearly 40,000 are members of families with children over 90 percent of which are headed by women. The rest of the shelter census is composed of nearly 5,000 members of “adult families” (couples without children) and almost 13,000 are single adults. The official count of unsheltered or street homeless is fewer than 3,000. Children growing up with the benefit of two parents are extremely unlikely to wind up homeless in New York.

Poverty and substandard living conditions have been constants throughout New York’s history. But the homelessness crisis is unique to modern times, as is the rise of the single-parent family. A very different sort of norms prevailed in the past, as explained in the following passage about family life among poor Jews in the South Bronx in the first part of the 20th century from Jill Jonnes’s powerful South Bronx Rising:

There was much marrying in haste after quick courtships, and repenting at leisure as husbands and wives discovered their many differences, always exacerbated by trying to raise a family with never quite enough money. And yet, no matter how bitterly the couples might quarrel, or however leaden the silences between them, they persevered in their marriages. There was no possibility of separation, much less divorce. It was not socially acceptable. Think of the children, think of the shame…In the Jewish culture, the family was too cherished to be easily cast aside.

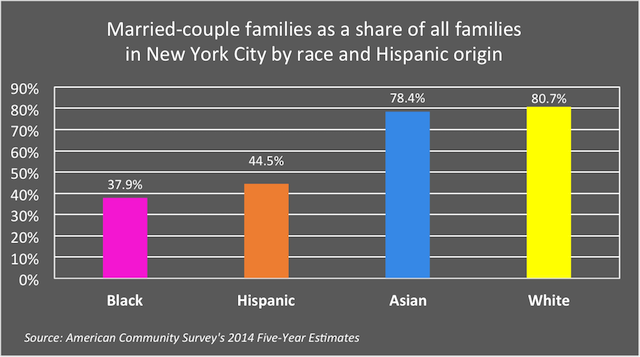

Like many immigrant cohorts before them, New York’s Asian population is proving the value of a resilient family structure in overcoming economic disadvantages. As the graph below shows, citywide, 78 percent of Asian families citywide are married couple families, compared with nearly 38 percent of black families. Asian single-mother-headed families are almost as likely as single-mother-headed black families to live in poverty in New York (24.1 v. 28.7 percent), but there are far fewer of them (roughly 34,000 v. 238,000).

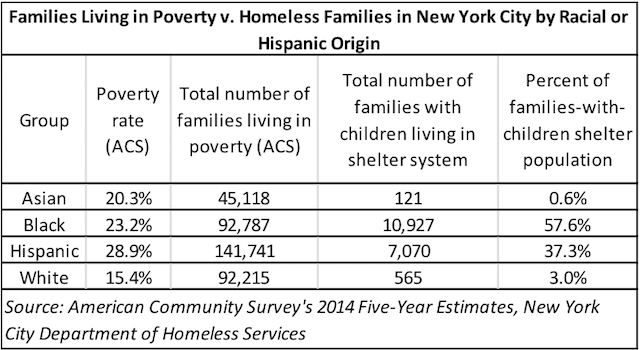

In New York City, Asians’ official poverty rate (20.3 percent) is well below that of Hispanics’ (28.9 percent) but fairly close to that of blacks (23.2 percent). The City’s annual “CEO Poverty Report,” which uses an alternative measure than the Census, finds that Asians have the highest poverty rate among all groups (see Figure 7 in the report). In absolute numbers, there are approximately twice as many poor black families as poor Asian families. But, as the table below shows, there are 90 times as many black families with children in the shelter system as there are Asian families with children.

Asians’ low rate of homelessness in New York is especially striking considering the cramped quarters many of them endure. “Doubling up” is often thought of as the penultimate stage to homelessness. Data from New York’s Housing and Vacancy Survey show that the “severe crowding” rate among Asian renter households is three times that of black households (see Table 7.51 of the report). In a 2014 study, the city’s Independent Budget Office found that the neighborhoods that contributed the most entrants to the shelter system in recent years were mostly black neighborhoods in the South Bronx and Brooklyn. Predominantly Asian communities in Queens and elsewhere did not even rank.

As Asians have maintained a certain resistance to declaring themselves homeless and entering a shelter, my colleague Howard Husock has speculated that, over time, norms have shifted in other poor minority communities. In his forthcoming Homelessness in New York City, Baruch College’s Thomas Main quotes a former de Blasio administration official who notes with satisfaction that the current policy of granting preferences for public housing units to homeless families has not led to any discontent among existing residents. When Mayor David Dinkins adopted a similar policy in the early 1990s, public housing residents protested over seeing their relatives on waiting lists passed over by the homeless. The former de Blasio official believes that the situation is different now because “at the end of the day, in poor families, homelessness is not such an unknown phenomenon. Your cousin has been homeless, your neighbor has been homeless, maybe you have been homeless at some point. The recognition is that homeless people are just like us, one paycheck away.”

This normalization of homelessness in New York is no doubt related to the city’s granting a special “right to shelter” and is viewed as an entirely welcome development by many advocates. For now, the point is simply that norms matter and norms change in reaction to official government policy. New York politicians by and large don’t want to hear about this. When Mayor de Blasio’s predecessor Michael Bloomberg launched a public awareness campaign aimed at explaining the enormous benefits of getting married before having children, it was denounced as “shaming already struggling teen parents.”

Certainly, there is not enough low-rent housing for poor New Yorkers. But expensive rental markets push a subsidized housing solution to the homeless problem beyond the reach of government budgets just as surely as they force many families into homelessness to begin with. Cities will never be able to manage, and still less end, homelessness without recognizing that it’s more than just an economic crisis.

Stephen Eide is a Senior Fellow at the Manhattan Institute.