Highlights

- Employment-related factors explained 31% of the increase in the proportion of Japanese men who were never married by age 30 in the youngest cohort compared to the oldest cohort. Post This

- More of the increase in the proportion childless at age 30 was explained by employment-related factors than by the increase in never being married at age 30. Post This

- Similar to other developed societies including the U.S., there has also been an increase in the number of inactive or unemployed, underemployed, and precariously employed men of prime working age in Japan. Post This

In the 1980s, I did some research on the authority attainment of men and women in the workforce in the U.S., with a focus on the factors that cause the sex difference in supervisory and managerial authority. One day I was discussing this research with a Japanese friend. She laughed when she heard about my research into what prevented women from moving into authority positions to the same extent men do, and told me, “in Japan, it would be on a sign on the wall.”

Things have changed in Japan over the last 40 or so years, and the workforce has opened up to women. Nevertheless, it is still a traditional society where women are expected to stop working when they have children, and the male-breadwinner model is firmly entrenched. Japanese women continue to express a strong preference for high income earning capacity in a marriage partner. It is not surprising, then, that men in Japan who are unemployed, underemployed, or low-wage earners are less likely to get married and have children. (In Japanese society, as in most east Asian societies, there is very little childbirth outside of marriage).

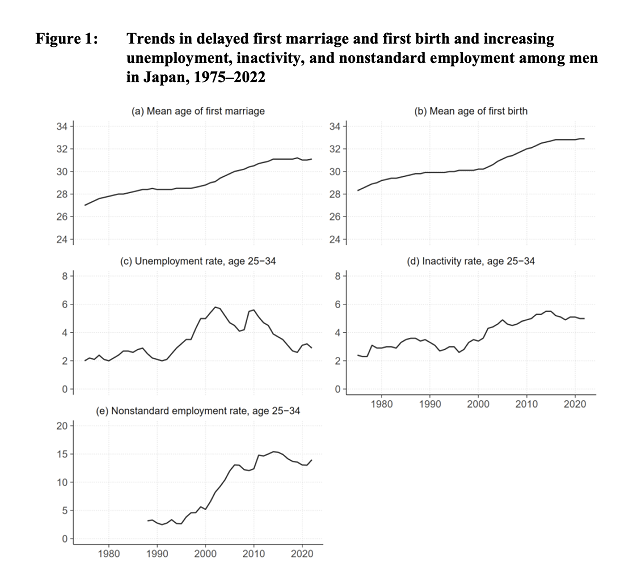

At the same time, Japan has moved from near universal marriage to declining rates of marriage, a pattern common to other east Asian societies. As in the U.S. and other developed societies, average age at first marriage has increased, as has average age at first birth and rates of childlessness. Again, similar to other developed societies including the U.S., there has also been an increase in the number of inactive or unemployed, underemployed, and precariously employed men of prime working age in Japan (see Figure 1).

Given the continued relationship between earning capacity and marriage for individual Japanese men, it is likely that much of the overall declining rates of marriage and family formation in Japan is due to the increase of employment instability among young men. To investigate the extent to which this is the case, Ryota Mugiyama used data on men born between 1945 and 1984 from the Social Stratification and Mobility Survey of Japan to find out how the increased employment instability of young men (measured by employment status and years spent in each type of employment status) has contributed to overall declines in marriage and fertility rates in recent cohorts of Japanese men.

His models found that employment-related factors accounted for 26% of the decline in the chance of first marriage for individuals from the first cohort (born 1945 to 1954) compared to individuals from the latest cohort (born 1975-1984). He also found that employment-related factors contributed 27% to the decline in the annual chance of first birth for individuals from the earliest birth cohort (1945-1954) to the latest birth cohort (1975-1984).

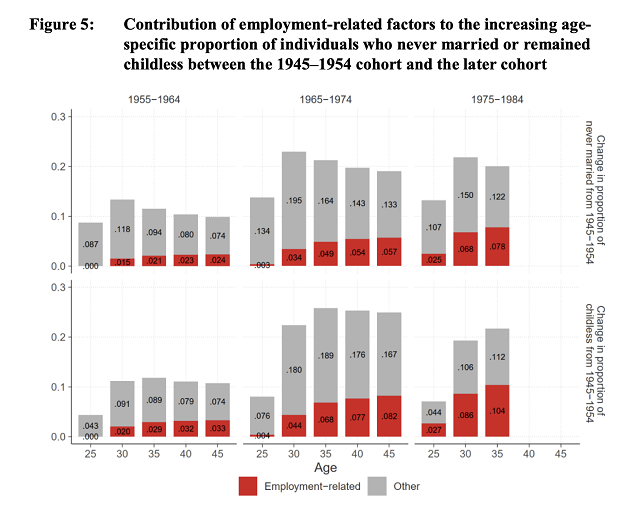

Regarding the overall decline in marriage rates, Mugiyama found that employment-related factors explained 31% of the increase in the proportion of Japanese men who were never married by age 30 in the youngest cohort (born 1975 to 1984) compared to the oldest cohort. Similarly, in the younger cohort, the contribution of employment-related issues explained 45% of the increase in the proportion childless at age 30 compared to the oldest cohort. More of the increase in the proportion childless at age 30 was explained by employment-related factors than by the increase in never being married at age 30, showing that even married men are remaining childless due to employment-related issues despite the traditional strong linkage between marriage and fertility in Japan.

These results support the contention that the increased employment instability of young men has contributed substantially to increasing average age at first marriage and first birth and the rising proportions of never-married and childless men in Japan. Of course, there are many other factors accounting for the decline in marriage and family formation in Japan, including the clash between the existence of greater educational and employment opportunities for women and the continued traditional division of labor in the home and the strong expectation of intensive parenting by mothers. Other factors include the increasing costs of housing and the tradition of extended coresidence of married couples with their parents.

While Japan is a unique cultural context, many of the same trends are observable in other developed societies such as the U.S., notably the increase in male unemployment, underemployment and employment insecurity and the decline of marriage and fertility rates. As in Japan, there is good evidence that the male breadwinner norm continues in the U.S. and that personal income and employment remain important for marriage and family formation for individual men. Thus, it is likely that the declining employment rates of prime age men in the United States, along with rising employment insecurity associated with the “gig” economy, help account for the overall decline in marriage and fertility rates in the U.S. as in Japan.

All of this suggests that any serious attempt to reverse the on-going declines in marriage and fertility rates across the developed world requires attention to male employment and economic status. Of particular concern is the declining participation of men in higher education, as lower levels of education are frequently associated with lower work force participation, more precarious employment, and lower incomes. As the prospects of stable and high-income employment fade for men, so do the prospects of a reverse in the current trend of lower rates of marriage and family formation in society as a whole.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life (Routledge 2016), editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018), and author (with Martin Fieder and Susanne Huber) of Not So Weird After All: The Changing Relationship Between Status and Fertility (Routledge, 2024).

*Photo credit: Shutterstock