Highlights

- The “decline in the two-parent family structure is the single biggest factor associated with the increase in child (official) poverty [i.e., excluding much safety-net income] between the mid-1970s and the early 1990s.” Post This

- Applying the SPM internationally, the U.S. has a slightly lower child-poverty rate than the U.K. and isn’t too far off from Ireland and Canada. Post This

A new report from the National Academies evaluating strategies to fight child poverty should have been a highly useful and truly bipartisan affair. On topics ranging from gun control to immigration, the organization has done a decent job of including researchers from across the political spectrum on its panels and evaluating studies in an exacting and methodical manner. One normally finishes such reports far better informed about the topic—and far less confident in one’s prior beliefs, whatever they were, given the high standards of rigor upon which the group insists.

Unfortunately, Congress ordered up something very different from the organization back in 2015. The group's new child-poverty report does not just summarize the relevant research and point out its flaws; by congressional edict, it must include a plan to reduce child poverty by half in 10 years. Since poverty is mathematically defined as having an income below a certain level (meaning you can, tautologically, end it by giving people money), and since methods other than simple transfers to the poor are controversial among the field's researchers and therefore lack scientific consensus (think: work requirements), the panel naturally suggests that the “evidence-based” way to achieve this goal is to take at least $90 billion annually and turn it over to poor families, and sometimes non-poor families, too, in a blizzard of cash transfers, wage and child-care subsidies, and in-kind benefits such as food stamps. That price tag adds up to more than $700 every year for every household in the country. And all this would come on top of current federal programs that already spend hundreds of billions of dollars a year on benefits for children.

In other words, Congress asked one of the nation's premier scientific bodies to grant its imprimatur to a proposal that sounds like it came straight off of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's website, by assigning it a task that couldn't be accomplished any other way. Well played, guys.

But if you ignore the headline-grabbing bottom line of the report, it actually does contain a semblance of the overly detailed and highly rigorous review of the scientific literature that we all cherish about National Academies publications. Here are a few highlights.

1. Child poverty has fallen.

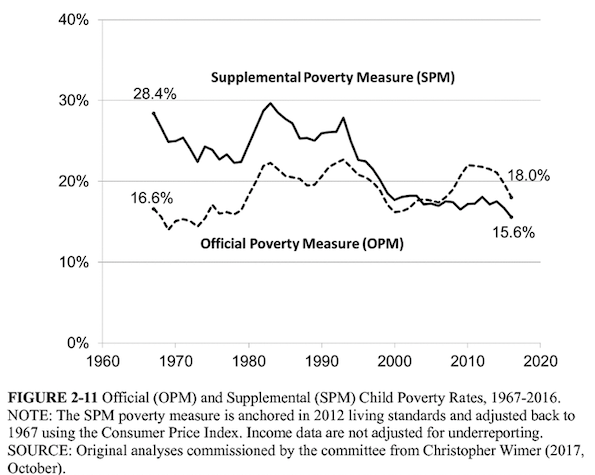

Conservatives were once fond of saying that we fought a war on poverty and poverty won. Fact-checkers who consulted the government's Official Poverty Measure were inclined to agree. The OPM, however, suffers from numerous flaws, most notably that it doesn't count a lot of welfare spending, such as food stamps, as income. The far superior Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) shows a marked decline in deprivation since the mid-1990s. Even the Great Recession is basically invisible.

The usual conservative line might be changing, too. The National Academies panel notes a recent Trump-administration report that called the War on Poverty “largely over and a success” and cited yet another poverty measure, one based on consumption rather than income, according to which child poverty was all the way down to 4% in 2016.

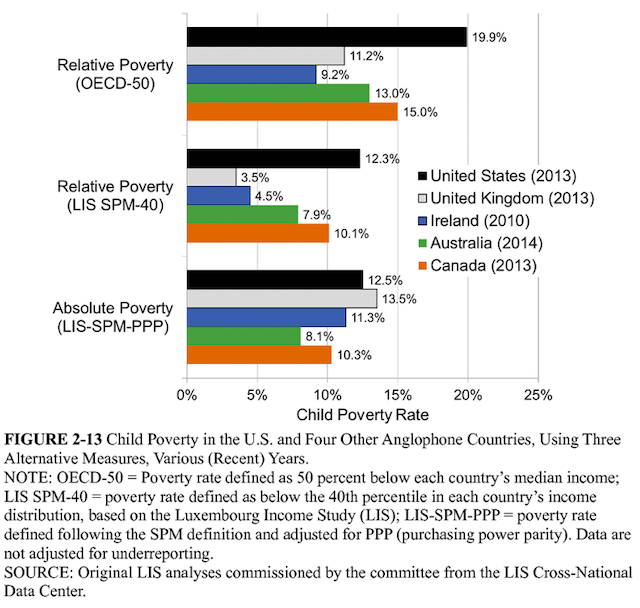

2. The U.S. does not, in fact, have astoundingly high rates of child poverty—at least, if by “child poverty” you’re referring to actual deprivation, as opposed to inequality.

Especially when making international comparisons, poverty researchers like to define “poverty” as half of each country’s median income—what’s known as a “relative” measure. The problem is obvious to anyone who thinks about it for half a second: it makes economic growth basically powerless to relieve poverty because growth increases the median income and thus moves the goalposts. Indeed, even if everyone’s income magically doubled at once, no one would rise out of poverty by this yardstick, because everyone’s relative income would still be the same. Coincidentally, this patently ridiculous—but mysteriously popular among some academics—way of comparing poverty rates is particularly rough on America, which has one of the highest standards of living in the world but puts relatively little emphasis on reducing inequality as such.

This chart from the report makes the point nicely. Applying the SPM internationally in “purchasing power parity” terms, the U.S. has a slightly lower child-poverty rate than the U.K. and isn’t too far off from Ireland and Canada.

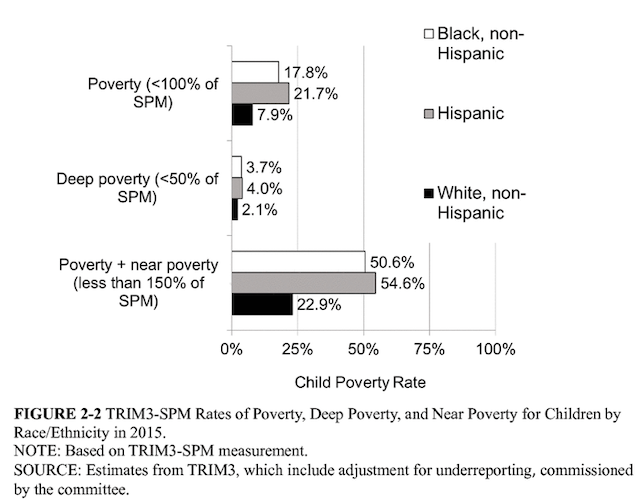

3. Child poverty varies immensely by racial group and nativity.

Another limitation of international comparisons is that many other countries don’t struggle with anything resembling our racial history, and the horrifying toll of slavery and Jim Crow is evident when you break the numbers down by race. White Americans have strikingly low child-poverty rates relative to blacks.

Meanwhile, as Family Studies contributor Kay Hymowitz recently noted, immigration has a role, too. Hispanics have even higher child-poverty rates than blacks do, and in general immigrant families (meaning there’s at least one foreign-born parent) have a child-poverty rate of about 21%, more than double the native rate of 10 percent.

The point here is not that high rates of child poverty are “only” among minority groups and nothing to worry about, but rather that we must bear our own unique history and immigration policy in mind here.

4. Efforts to fight child poverty vary in their effectiveness . . . and in their cost-effectiveness.

The authors highlight four different “packages” of policies that, per their simulations, could significantly reduce child poverty in the short term:

- The “work-oriented” package expands the earned-income and child-care tax credits, raises the minimum wage to $10.25, and rolls out a job-training program called WorkAdvance. (Minimum-wage hikes may reduce employment, but they also result in higher pay for workers who keep their jobs, which lifts some out of poverty. Obviously, this trade-off looks different depending on which studies you rely on, and the panel may have gotten it all wrong.) This plan reduces child poverty by 19% (from a baseline of about 11 million in 2017), adds about a million workers to the workforce, and costs $8.7 billion per year.

- The “work-based and universal support” package combines the previous proposal’s tax credits (but not the minimum wage or job training) with a $2,000 child allowance, which reduces poverty but also cancels out some work-force gains by reducing work effort: 36 % child-poverty reduction, 570,000 new workers, $44.5 billion cost.

- The last two packages reduce child poverty more than half by combining some of the above measures with still others, including expanding food stamps and housing vouchers, beefing up the child allowance to $2,700, and eliminating restrictions on welfare use by immigrants. They cost upward of $90 billion per year and would add, at most, about 610,000 workers.

Some may say the first option is clearly inferior, as it doesn’t reach even half the goal of reducing poverty by 50%, but it’s far and away the most cost-efficient and the most work-promoting, not to mention the most politically viable. Nearly half of its poverty-reducing potential comes from encouraging employment as opposed to just transferring money to poor parents. It would eliminate more than 2% of child poverty for every billion dollars spent, vs. 0.8% for the second and 0.5–0.6% for the final two. It also would not entail no-questions-asked transfers of $2,700 per child to every parent, expanding access to food stamps and subsidized housing, or giving up the commonsensical idea that immigrants granted the privilege of coming here should be fully responsible for supporting themselves.

However, it’s also worth noting that the work package’s price doesn’t take account of the costs to businesses of the higher minimum wage, which after all can be seen as a tax on employing low-skill workers. In fact, hiking the minimum wage is counted as a negative $3.7 billion cost to the government, since when workers earn more money, they use safety-net programs less and pay more in taxes, and it reduces child poverty just 1.3% (Not percentage points. Percent. So, starting at 13% of children in poverty, the reduction is less than 0.2 points.)

5. Marriage reduces poverty, but we have no idea how to increase marriage.

The authors report that the “decline in two-parent family structure is the single biggest factor associated with the increase in child (official) poverty [i.e., excluding much safety-net income] between the mid-1970s and the early 1990s” (while increases in maternal employment are largely responsible for the rebound since then). They write that increasing the number of kids in two-parent families “would almost certainly reduce child poverty.” However, they also state that marriage-promotion programs have been pretty much a bust (although, see Alan Hawkins’ recent IFS blog on this issue for more recent research findings on marriage and relationship education programs).

6. We could use more research on work requirements.

The absence of work requirements even from the “work-oriented” plan has proven rather annoying to some of my fellow conservatives, given that such requirements have been a core plank of conservative poverty policy going back to the 1996 welfare reform and were implemented after extensive experimentation in the states. There is good evidence that the reforms of the 1990s, taken as a whole, were helpful, though it's hard to isolate the role of work requirements in particular (as opposed to, for example, expansions of the earned-income credit).

For their part, the National Academies panelists note that “[s]ome of the strongest evidence in support of these programs comes from randomized controlled trials that were published in the 1990s” and that the 1996 reform “reduced welfare receipt and increased employment.” However, they claim that work requirements are “at least as likely to increase as to decrease poverty”—different ways of implementing the policy yield different results—and they decline to extrapolate from the 1990s studies to their simulations.

This is frustrating, but if there’s one thing everyone should be able to agree on, it’s that we need rigorous studies—ideally randomized controlled trials—as we experiment with strengthened work requirements in food stamps and even adding such requirements to Medicaid.

***

In insisting on an “evidence-based” plan for reducing child poverty by half in just 10 years, Congress stacked the deck in favor of raw transfers to the poor, and thus not much can be concluded from the fact that the panel endorsed a combination of such transfers. But the report remains worth reading because it contains a wealth of information that challenges left and right narratives of poverty alike.

Robert VerBruggen is a research fellow at the Institute for Family Studies and a deputy managing editor of National Review.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.