Highlights

- Large-scale female feticide has been taking place among certain U.S. sub-populations over the past decade, per a new analysis. Post This

- Abnormally high SRBs appear to be delimited in the US to foreign-born populations hailing from countries beset by that same problem. While we cannot be conclusive, we do not find evidence of such SRB imbalances among Asian-Americans born in the USA. Post This

In a 2011 study titled “The Global War Against Baby Girls,” one of us (Nicholas Eberstadt) presented troubling evidence that new and biologically unnatural imbalances in sex ratios at birth were emerging in Eastern Asia, Southeastern Asia, South Asia, Western Asia, and elsewhere. In one country after another, demographic data were registering a surfeit of male infants—excesses far above what would have been expected from the universal norm of roughly 103-105 baby boys for every 100 baby girls observed in large human populations throughout history. These ominous new trends, we theorized, were explained by mass female feticide: a phenomenon driven by the collision of ruthless parental son preference, low fertility levels (whereby the gender outcome of each birth took on added import for parents), and the advent of widespread and inexpensive prenatal gender determination technology in the context of easily available or unconditional abortion.

We noted that rising levels of income and educational attainment did not preclude abnormally high sex ratios at birth (or SRBs)—to the contrary, in some countries SRBs seemed to be rising along with national affluence. And we warned there was no reason to think this disturbing practice could not come to Western countries: rather, initial research on the situation in the U.S. and the UK at the time of that report suggested the possibility that sex-selective abortion may be common to other subpopulations in developed or less developed societies, even if these do not affect the overall SRB for each country as a whole.

As we begin the 2020s, this may be a good time to revisit the issue of unnatural SRBs and the question of whether America has become a battlefield in “the global war against baby girls.” Such an inquiry is all the more timely thanks to revisions in U.S. official vital statistics protocols, which now offer more detailed natality data than were available for the aforementioned study.

These new data are worrisome, if not alarming—for they demonstrate that large-scale female feticide has been taking place among certain U.S. sub-populations over the past decade. Yet we may also see some measure of reassurance in these numbers, for the problem of unnaturally elevated SRBs appears to be peculiar to particular immigrant groups and circumstances, with no indications that it carries over to second generation parents born in our country.

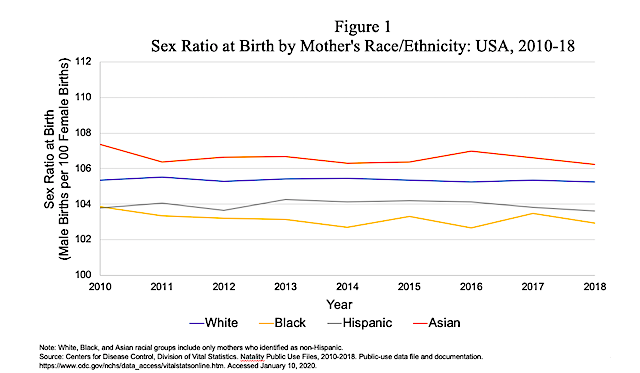

Overall trends in U.S. sex ratios at birth for 2010 to 2018 (the most recent year for which such data are publicly available) may be seen in Figure 1.

In the 2010s, as in previous decades, the overall SRB for the Unites States hovered near 105. This overall average, though, masked differences according to maternal race or ethnicity, as defined and measured by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. SRBs for non-Hispanic Whites, for example, were consistently just over 105, fluctuating only within a very narrow range. SRBs for Hispanic mothers were lower—about 104—but likewise were quite steady from year to year, while SRBs for Black mothers trended around 103 boys for every 100 girls.

Asian-American SRBs are another story altogether. For one thing, variations in SRBs are higher for this group than for other ethnicities in America. Most important, SRBs for Asian-American mothers were strangely high in the 2010s—averaging 106.6 boys per 100 girls. This is a curiously elevated level—and with over two million births to Asian-American mothers over those nine years, the finding cannot be dismissed as an artefact of small sample size. It merits further scrutiny and deeper analysis.

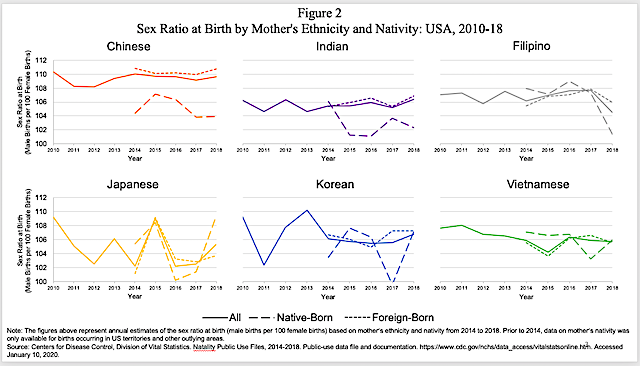

We provide a more detailed disaggregation of SRBs between 2010 and 2018 for Asian-American mothers in Figure 2.

Since 1992, U.S. birth statistics have broken down the overall Asian-American population into several major sub-categories by mother’s ethnicity, including Chinese, Filipino, Indian (not to be confused with Native-American), Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and “Other.” Furthermore, since 2014, U.S. natality data distinguish between native-born and foreign-born mothers. Thus, we can show annual SRB trends by nativity for the six largest Asian-American ethnicities for recent years (omitting the catch-all “Other” category, whose SRBs for 2014 to 2018 were unexceptional for foreign- and native-born mothers alike, each of these falling between 104 and 105).

As Figure 2 demonstrates, there is considerable annual fluctuation in SRBs for these sub-populations: a result one might expect given the small sample sizes in some of these cases. With respect to “outlier” SRBs, one of these sub-populations in particular stands out. This is foreign-born ethnic Chinese mothers: between 2014 and 2018, their SRB was consistently above 110. The second grouping of interest is foreign-born, ethnic Indian mothers, for reasons that momentarily will become apparent, even though their overall 2014 to 2018 SRB was a considerably lower 106.0. (Some of the other SRB trends in Figure 2 may also raise eyebrows, but we are not confident these are statistically meaningful, as we will soon see.)

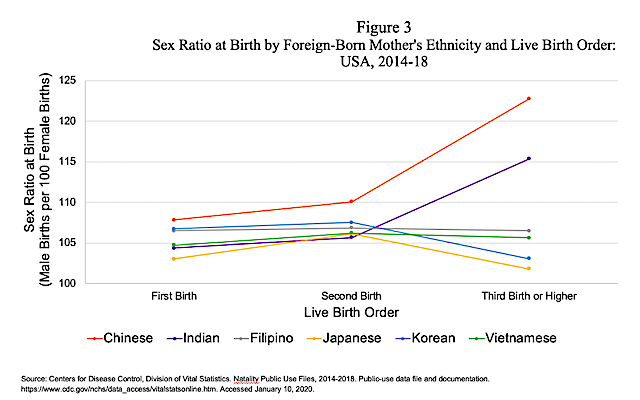

In China, India, and elsewhere, research has demonstrated that abnormally high SRBs nowadays tend to be more extreme at higher “parities” (that is to say: birth order), indicating that parents in societies where mass female feticide occurs are much more likely to opt for sex-selective abortion if they already have a child or two, especially if those previous births were daughters. In Figure 3, we show SRBs for foreign-born, Asian-American mothers for 2014 to 2018 by birth parity.

What jumps out, of course, is the SRB trajectory by live birth order for foreign-born mothers of Chinese and Indian ethnicity. Note there is no obvious “parity effect” among foreign-born mothers from other Asian ethnicities—indeed, for Korean and Japanese mothers, SRBs appear to be slightly lowerfor third births than for first births.

For foreign-born, Indian mothers, on the other hand, the SRB for third and higher-parity births between 2014 and 2018 was an unnerving 115.3. The corresponding figure for foreign-born, Chinese mothers was a shocking 122.8: but for first and second-parity births, SRBs were, respectively, 107.8 and 110.1—uncomfortably high levels, too.

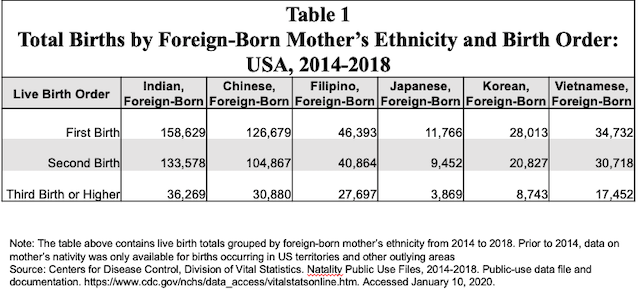

How many newborn girls are “missing” from these two American sub-populations? We cannot say for sure—but we can offer illustrative estimates, drawing from the data in Table 1.

If we posit a hypothetical “norm” of 105 for the “natural” SRB for foreign-born mothers, the data in Table 1 would imply over 1,700 “missing” births of newborn girls between 2014 and 2018 among third and higher-parity deliveries for foreign-born mothers of Indian ethnicity. By the same token: such calculations would hypothesize over 6,700 “missing” newborn American girls to foreign-born, Chinese mothers between 2014 and 2018 (summing all birth orders). By such an illustrative reckoning, the scale of the “missing female newborn” group in these two sub-populations would have been on the order of 8,400 for 2014 to 2018 alone. The obvious inference is that many thousands of baby girls were “missing” due to parental interventions: i.e. sex-selective abortion—though it is equally obvious that we have no means of telling exactly how many sex-selective abortions took place among these groups over those same years, much less in which countries or states such procedures would have taken place.

Regardless of whether one identifies as pro-life or pro-choice, readers may be highly unsettled by these findings. Our figures suggest all but incontrovertibly that the “global war against baby girls” has opened a front in the United States of America.

We say “almost incontrovertibly” because there is always a possibility in statistical analysis that the results under consideration have been arrived at purely by chance. But it is important to understand how utterly astronomical the odds would be for a random occurrence of such SRBs. Given the number of births under consideration between 2014 and 2018, the SRB for third-parity births to foreign-born, Indian mothers could have been random: but if the “norm” for this population was truly an SRB of 105, the odds of observing an SRB of 115.3 by sheer chance would be 23 million million millionto one. Similarly, if 105 were the actual “norm” for SRBs for foreign-born, Chinese mothers, the odds against the observed SRB from 2014 to 2018 of 110.4 would be 7 million million million million million millionto one. (By way of comparison, demographers estimate that something like one-tenth of a million millionhuman beings have been born since the dawn of our species.) Statistical techniques, to repeat, deal only with probabilities. That said: our findings look to come just about as close to certainty as any social science results can claim.

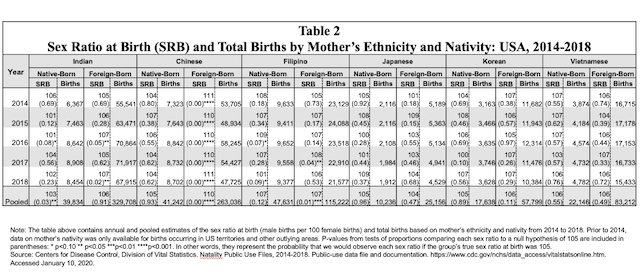

This is the bad news—and that bad news is truly distressing. But there is arguably good news to be seen here as well, and we show it in Table 2.

This table presents sex ratios at birth by ethnicity and nativity for Asian mothers for the 2014 to 2018 period, and examines the likelihood that the reported SRBs differ from our expected level of 105 simply by chance.

As may be seen, SRBs for Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese mothers cannot be meaningfully distinguished from our posited norm—and that holds for foreign- and native-born mothers alike. Moreover, our analysis provides no “statistically significant” evidence that SRBs for US-born, Asian-American mothers of any ethnicity actually exceed such a “norm”.

In other words: even though some of these sub-populations (in particular, native-born, Filipino and Vietnamese mothers) reported SRBs in the 106 to 107 range for 2014 to 2018, it is impossible to reject the hypothesis that these were simply chance occurrences—and for the other Asian-American ethnicities (Chinese-, Indian-, Japanese-, and Korean-Americans), native-born mothers reported SRBs of 105 or lower during those same years.

The situation with regard to abnormally elevated SRBs in the United States merits further and continuing scrutiny. Some groups (such as foreign-born, Filipino mothers) had suspiciously high SRBs over the 2014 to 2018 period: we would be well served to monitor future trends here, for example.

But abnormally high SRBs appear to be delimited in the US to foreign-born populations hailing from countries beset by that same problem today. While we cannot be conclusive about this matter, we do not find evidence of such SRB imbalances among Asian-Americans born in the USA. One explanation for such a distinction in SRBs would be that assimilation and acculturation are helping to bring this concerning practice to an end. That is not be the only possibility, but it is a plausible and rather hopeful one.

Nicholas Eberstadt holds the Henry Wendt Chair in Political Economy at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in Washington, DC. Evan Abramsky is a Research Associate at AEI.