Highlights

On average, children growing up with both biological parents have higher educational attainment than those in nontraditional families, girls generally outperform boys, and higher income also predicts higher-than-average education. Despite the stability of these generalizations, the interaction between these predictors (family x gender x income) is less predictable, and it has changed dramatically over time (family x gender x income x time).

Family x gender. Children not growing up with both biological parents are more likely to live with their mothers than their fathers. In theory, this could mean that boys’ education takes a bigger hit when parents split up than girls’ education does. While boys and girls are affected alike by decreased resources, girls might be relatively insulated from the emotional costs of family instability as they are less likely to be separated from the parent to whom they are closest, and they are more likely to have frequent contact with a same-sex role model. In addition, fathers may be more effective than mothers in supervising the actions of adolescent boys. Even though this “same-sex hypothesis” has been questioned, the idea that good outcomes among boys require greater parental time investment has garnered wider support. Overall, then, nontraditional family structures seem to negatively affect boys more than girls—at least when it comes to more obvious outcomes.

Family x gender x income. To date, logic pointing toward deeper penalties from nontraditional families among boys has informed research on gendered diverging destinies. The term “diverging destinies” refers to how the class divide in the retreat from marriage results in the costs of not growing up with both biological parents falling disproportionately on lower-income youth. The education of those from lower-income homes not only suffers from material hardship and (often) lower-quality schools, but these children are also likely to enjoy less time with their parent(s). This is because the retreat from marriage is more common among the less advantaged than among the wealthy. In short, the wealth gap creates separate destinies, and the erosion of marriage can cause destinies to diverge even further (family x class). If boys’ education is compromised more than girls’ when the time resources of both parents are not available in the household, then the destinies of lower-income boys would diverge still further—the gap in education by family income would be even greater among boys than girls.

Yet two leading sociologists of relationships and inequality, Diederik Boertien and Fabrizio Bernardi, reached a different conclusion in their recent study, “Gendered Diverging Destinies.” They found a wider class gap in college attainment for daughters than for sons.

Family x gender x income x time. Their conclusion derives from a sound approach that the researchers have long advocated, namely paying attention not only to risk exposure, but also to variation in the size of the risk.1 They correctly maintain that if all we know is that two-parent homes are becoming less common, especially among the poor, we still don’t know whether destinies are diverging over time until we also factor in whether the size of the dual-parent advantage differs between groups and/or changes over time.2 They refer to this last component as heterogeneity in the penalty associated with nontraditional family structures. If the penalty were consistent (homogeneous), then changes in the exposure to risk would tell the whole story (the group with more growth in nontraditional families would have the worst educational trajectories). In contrast, Boertien and Bernardi argue for assessing the size of the penalty at various intersections of family, gender, income, and time.

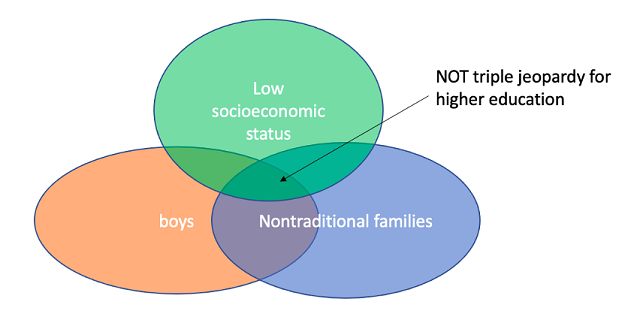

Put differently, being male, coming from a low-income family, and not being reared by both biological parents are all educational disadvantages. If the intersection of these disadvantages was simply the sum of the cumulative disadvantages (or if disadvantages compounded when they intersected), the class gap in college attainment would be wider among sons than among daughters. The triple jeopardy boys face would also be expected to deepen over time in countries like the United States where higher-income families have been slower to depart from a traditional family structure.

Instead, the educational penalty for boys in low-income nontraditional families is particularly small. That is, Boertien and Bernardi show that coming from a low-income family lessens the disadvantage otherwise experienced at the intersection of maleness and nontraditional families.

Circling back to what this means for gendered diverging destinies, the growth of nontraditional childrearing arrangements has not contributed to inequality among men as much as it has among women. How do we understand this in practical terms?

Even though four-way interactions (family x class x gender x time) are necessarily complex, the story here can be told using relatively simple vocabulary. Boertien and Bernardi have often described lower-income boys as “not having much to lose” from disadvantageous family structures. It is helpful to envision this as a floor effect, i.e., among those already at the bottom, further disadvantages do not cause any further drops. The educational careers of low-income boys typically end short of a bachelor’s degree whether or not their parents raised them together.

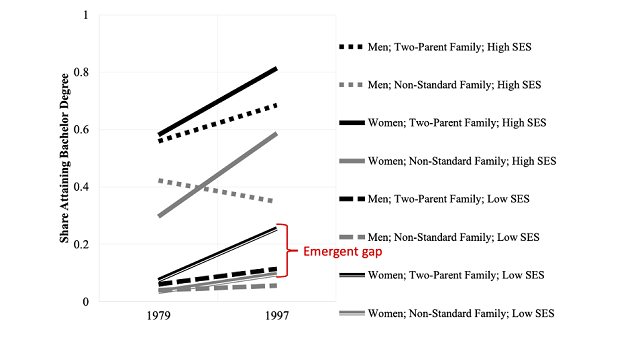

But why have girls’ destinies diverged? Educational progress has been fantastic for higher-income girls in nontraditional families, so that is not the reason. That is a success story we need to understand in case it informs how to support the educational attainment of other youth in nontraditional families. Rather, divergence has occurred because college prospects for low-income girls have improved more rapidly in dual-parent families than nontraditional families (see the figure from the study below). Among all low-income children, daughters from intact families have seen the most educational improvement over time.

Source: D. Boertien and F. Bernardi. “Gendered Diverging Destinies: Changing Family Structures

and Inequality of Opportunity Among Boys and Girls in the U.S.” SocArXiv. March 17, 2020.

On the basis of this last observation, I can make a prediction for the future that Boertien and Bernardi did not. They call for more attention to why nontraditional families carry such heterogeneous penalties across gender, income, and time. Such attention is clearly appropriate, but we should also consider a likely outcome if educational effects continue to improve on average: more boys would have even more to lose from not growing up with both parents. If low-income boys had a better chance of finishing a four-year college degree, family structure could start to predict success better than it does now when so many sons of less-educated mothers can’t fall because they are not climbing off the floor.

I cannot applaud diverging destinies among girls in their own right—the growth of socioeconomic inequality is problematic in a myriad of ways (here is just one that I have written about recently). Nonetheless, diverging destinies are a marker of the early stages of positive educational progress among low-income girls, and we should all welcome similar progress among low-income boys.

Laurie DeRose is a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Catholic University of America, and Director of Research for the World Family Map Project.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.

1. In technical terms, this is an Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition.

2. The short form description here focuses on the possibility of rates differing and changing over time. The Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition also allows the size of the groups (levels) to change over time.