Highlights

- In a low-wage economy, where even two parents working full-time might just barely cover the cost of basic necessities, a child allowance could act as a kind of wage subsidy for working-class families. Post This

- Many low-income people value marriage and desire it but are often living in a day-to-day survival mode that precludes the extra expense of getting married (both the wedding cost and the marriage penalties they face). Post This

At their wedding this past September, Savannah wore an orange gown with rhinestones around the waist, and Rob sported a matching orange shirt and tie as he held their infant daughter, dressed in yellow ruffles and bow. But before they planned the wedding, they sat down to talk about taxes.

“We did sit down and discuss, ‘Well, okay, you make this much and if we get married it’s going to take away from everything else that we have,” Savannah shared. “So I did take that into consideration before we got married.”

The couple from southwestern Ohio has five children between them—ranging from ages 11 months to 12 years—and figured out that marriage would mean getting significantly less money at tax time. “We both combined made $64,000 last year which ended up docking us from getting the Earned Income [Tax] Credit that I would get myself,” Savannah explained.

The couple already filed their taxes this year, and Savannah estimates that if they weren’t married, they would have received “like twice what we did get”—which would amount to an extra $5000. “So that does take a toll on families when they get married at the end of the year, too.”

It’s a predicament that other couples also find themselves in, due to the marriage penalties associated with the EITC. The current conversation about policy solutions ranges from simplifying the EITC and the child allowance in Romney’s Family Security Act, to increasing the income threshold for married couples and phasing out the EITC more slowly, as in this recent proposal by Angela Rachidi and Robert Cherry.

Marriage Disincentives in Other Programs

Rob works as an automotive technician, a field he has been in for the last 15 years. Before the pandemic, Savannah worked at a nursing home as a dietary manager but did not return to work after maternity leave because her older children were doing remote schooling and needed her at home. To pay the bills, Rob picked up an extra part-time job at a pizza company. He works his day job from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. and then delivers pizzas from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. four nights a week.

“It’s working out,” Savanah told me. “We make enough to pay the bills and everything. But it’s kind of stressful…. He definitely misses being at home with the kids more.”

Unfortunately, that hustle puts them just above the threshold for much government assistance. In addition to the EITC, getting married cost Savannah in SNAP benefits, which she will be losing because Rob’s income is too high. “I don’t know that many people who have higher income like we do,” Savannah says. “Most of the friends that I have are from [public housing] where I used to live at before. But I feel like the more money you make, the more you get taken away from you. You’re trying to better your life for the kids you have, but then…I feel like I’m getting punished. Like all our help just gets taken away.”

She told me she likes the idea of a child allowance that would not be as prone to these kinds of marriage and work penalties. She wouldn’t worry about losing food stamps or the possibility of getting evicted because the allowance could be used for groceries and rent.

“I feel like if everybody were to get that extra amount of income and then on top of working – they wouldn’t have to be so stressed out and work these long hours, work double shifts just to sit here and pay everything they need,” she said. In a low-wage economy, where even two parents working full-time might just barely cover the cost of basic necessities, a child allowance could act as a kind of wage subsidy for families, who would still get some extra help, and that help wouldn’t go away because they get married or pick up part-time hours delivering pizzas.

The Meaning of Marriage

In the end, despite the steep penalties they faced, after almost four years together, Rob and Savannah did get married. It’s worth asking, why?

For Savannah, it had a lot to do with the good of their children. “I think that having two parents be there for a child that they made together would be better than just being like ‘Well, I don’t need somebody else, I’m going to do this on my own,’” she said. Savannah’s parents divorced when she was young and the experience shapes her beliefs today: “I think that marriage should still be an important thing when taking care of a family and children.”

Many of the young adults that I’ve interviewed in the past decade feel similarly about marriage. When I first met her 10 years ago, Brittney, a single mom who is now a manager and lead driver at another pizza company, told me that marriage is “the last step that you do in a commitment” and the point when you begin “living your life for each other and not just yourself.”

Back then, she told me, “I don’t think it has anything to do with your taxes.”

When I called her this past weekend to get her views on a child allowance, she told me,

We’ve talked about how important marriage is to me, and again it comes back to, if you won’t get married over this little check [a child allowance], then maybe you didn’t have strong beliefs about marriage anyway. I’d rather have a long-lasting love and work for things than to just rely on that little bit of help…. I don’t think I would turn down marriage for it.

However, she clarified that she currently can’t afford to lose the public housing where she is living. And even though she has a boyfriend of two years and thinks they’ll get married one day, she told me marriage is going to have to wait until her kids are grown because she never wants to put them through another eviction (they’ve been through two), and right now public housing seems the only way to ensure that.

“This is our stability,” she said of public housing. “I know it sounds messed up, but I have to put them first. So if somebody really loves me, they’ll just wait and understand.”

In other words, Brittney does not believe that a child allowance would be a marriage disincentive, even though having public housing is a disincentive for her because, despite working 40 hours a week, she doesn’t make enough to afford rent in the current housing market. But since she has four children, a child allowance could conceivably cover the cost of rent elsewhere, eroding her reliance on subsidized housing and helping her to feel financially stable enough to marry.

It’s unfortunate that people who believe in marriage and want to marry have to make these kinds of calculations at all. It’s particularly unfair that while marriage penalties have been largely eliminated from the tax code for the more well-off, poor and working-class parents are regularly put in the position of choosing between benefits and marriage —between financial stability or family stability for their kids.

Marriage and the American Dream

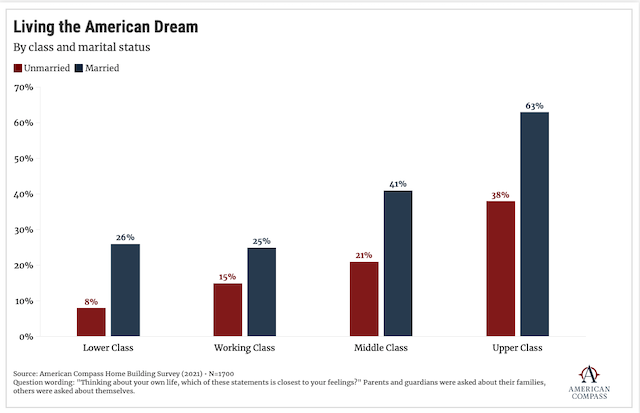

Whatever elite scripts say about marriage, in the popular imagination, marriage is still connected to the American dream. It’s why Ashley, a mom living in public housing who just happily celebrated her one-year wedding anniversary, tells me that despite financial stress, her life as a married woman is “too good to be true.” In fact, as illustrated by the chart below, a recent American Compass survey finds that: "Married people in the middle class are as likely to say they are living the American Dream as unmarried people in the upper class. Married people in the lower and working classes are at least as likely to say they are living the American Dream as unmarried people in the middle class."

In the popular view, marriage is forward motion, a sign of success, a step away from stigma. Cortney, a mom of two who works at The Dollar Tree, told me recently about her boyfriend’s marriage proposal and the new job he is starting. “So our little foundation that we have now is just going to grow bigger. And it’s going to better not only just ourselves but mainly the kids,” she said. She used the analogy of a ladder and sees marriage and employment as steps to stability—“We’re just climbing that ladder until we reach our spot where we need to be.”

The family is currently living with a friend after being evicted a few days before Christmas. But Cortney tells me that after her boyfriend’s recent marriage proposal, she feels a “glow” of hope unlike anything she has felt in recent years. Cortney is ecstatic as she relives the memory of his proposal, telling me, “Amber, I just bawled and bawled and bawled.”

For many people, marriage retains such meaning, and social science research continues to identify it as a key predictor of social mobility. For these reasons, it is high time that something is done—whether through Sen. Romney’s proposal or some other means—to remedy the unfair marriage penalties facing lower income Americans in the EITC and elsewhere.

The beliefs and attitudes expressed by people like Brittney and Cortney suggest that many low-income people value marriage and desire it but are often living in a day-to-day survival mode that precludes the extra expense of getting married (because of both the wedding cost and the marriage penalties they face). If this is the case, then conservatives can worry less about whether additional resources like a child allowance will lure poor families away from marriage and focus instead on reforms that empower people to act on their deeply-held aspirations for forming a more stable union.

Amber Lapp is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies and co-investigator of the Love and Marriage in Middle America Project, a qualitative research inquiry into how white, working-class young adults form families and think about marriage.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or viewpoint of the Institute for Family Studies.