Highlights

- Far from subsidizing single parenthood, Sen. Romney's proposal would actually move the tax code towards a more marriage-friendly position. Post This

- The worthy and honorable work of raising children should not be treated as an inferior good, as something policymakers would happily swap for a few more hours sorting packages at a factory. Post This

- Who benefits from Romney's plan? Most people. The benefits are largest for families with three or more kids, but even many childless households stand to benefit. Post This

Last week, Senator Mitt Romney (R-Utah) introduced a proposal to replace the current Child Tax Credit (CTC) and Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) with a new child allowance and reformed EITC. The plan has received a lot of attention from centrist and left-leaning outlets for obvious reasons: it proposes direct cash transfers to families, and it’s designed in such a way that it could be made into permanent law with just 51 votes in the Senate through a procedure known as “reconciliation,” basically allowing it to evade the threat of a Republican filibuster. This makes Romney’s plan the likeliest candidate for how Democrats and pro-family Republicans could achieve their longstanding goal of providing more direct support for children and families.

But many conservatives have responded to Romney’s plan with some skepticism. Basically, conservatives have raised three concerns about child allowance schemes in the past:

- Won’t a new child allowance program increase the deficit by a huge amount?

- Won’t more direct cash grants for kids lead to more single parenthood and unstable families?

- Won’t more cash grants discourage poor people from seeking employment, and thus keep them trapped in poverty even longer?

The good news is that Romney’s proposal is designed with these concerns in mind.

The first is the easiest to deal with: the Romney plan is budget-neutral; it does not increase the deficit. It would provide a new child allowance and a reformed EITC by removing money from other current programs. Specifically, the plan would phase out some bad features of the EITC (more on that below), would end direct cash federal welfare to families (the program called “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families”), would remove a special filing status that provides advantages to single parents (“Head of Household”), and would repeal what remains of the state and local tax deduction (SALT), as well as a daycare-related tax deduction mostly claimed by higher-income households. In simple terms, Romney proposes to pay for his proposal for a child allowance by swapping out some programs that benefited these families in the past, and also by discontinuing the federal subsidy for high taxes in New York and California.

But answering the latter two concerns is more complicated. To address them, it’s important to understand how the new plan compares to current policy.

Qui Bono?

There are two major pieces to Romney’s plan: a child allowance and a reformed EITC.

The child allowance would amount to $4,200 per year for kids under 6, and $3,000 per year for kids 6 and over. Families would get a monthly check beginning in the third trimester of pregnancy. This minor policy tweak would almost certainly reduce the abortion rate, as it did when Spain adopted a similar policy.

Currently, the Federal government provides a $2,000 Child Tax Credit (CTC) per child. The CTC is a complicated animal. People with less than $2,500 in income can’t receive it at all, and the credit “phases in” at a rate of 15 cents on the dollar. Part of the credit is refundable, which can lead to a “negative income tax,” but not the whole thing. The result of this approach is that 1) families receive the benefit associated with their kid retroactively, or after they might have used money on that child, 2) families get the benefit in a lump sum, and 3) many families never “receive” the CTC at all because it only reduces their taxes owed, never landing in their bank account. Furthermore, the way the phase-in works, many low-income people are excluded from the CTC. On the other hand, because the CTC phases in, it encourages people to work: a person in the CTC phase-in income range (generally less than $30,000 in income, depending on the number of children) might get $15 extra from the CTC for every $100 extra they earn, giving them extra incentive to get a job.

In sum, the CTC is a very complicated, indirect way of supporting families. Most families will never think very much about how it’s calculated. But those who do may notice a pro-work element to the CTC that is only for people with kids.

The EITC is even more complicated. Right now, there are eight different EITC benefit calculations, depending on marital status and number of children. But the simple version is, the EITC gives extra money to people who are employed and working, but whose incomes are still low. It’s a way the government encourages work and helps people make ends meet even if wages are very low. The EITC gives you a lot of money (up to over $6,000 per year) if you 1) have kids, 2) work about 30 hours a week at minimum wage, 3) stay unmarried. The current EITC is less generous for married people, and the generosity rises with each kid. Academic research suggests the EITC as it currently exists discourages childbearing on net.

The EITC does a lot to encourage work among the people for whom it is most generous. That is, among single moms, the EITC boosts employment. If you are poor, unmarried, and have custody of 2 or 3 kids, the EITC will do a lot for you. But if you get married, you’ll lose a lot of your benefits. If you’re childless, the EITC does very little. The EITC is a weird policy where we basically pay single moms to stay single, take a low-wage job, and then put them in a situation where they may need free help with caring for or raising their kids because the low wages do not really yield enough income to pay for day care while they are at work. To make things worse, the EITC is so complicated to file that a quarter of eligible people miss out on it, and a third of payments made are to people who weren’t really eligible.

Romney’s plan tackles this tangled mess of a program head on. It simplifies the 8 credit rates down to 4, it removes the favorable treatment of single parents, and it also provides more aid to childless people. This is all as it should be: punishing poor people for getting married creates a poverty trap. While we don’t want to encourage people to marry just for taxes, Romney’s plan doesn’t create a huge marriage benefit, it just removes a currently large marriage penalty.

The larger benefit for childless people may sound odd, but it makes a lot of sense. Childless people have fewer responsibilities at home. If they are out of work and school, the odds are that their use of time isn’t extremely socially valuable, so it’s important to provide some work incentive there. But for parents, this calculation is more ambiguous: a parent who isn’t employed may be doing the socially valuable work of raising their children. There’s no reason why the government should want people with kids to be employed more than it wants childless people to be employed. The Romney proposal still keeps a small benefit for having kids in the EITC, but it’s much reduced.

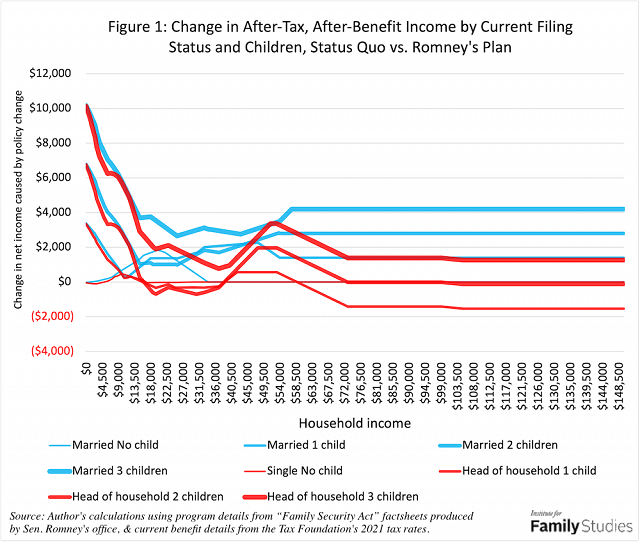

There are some other changes included too, like ending TANF and the Head of Household filing status, but graphs may be easier than words to describe the changes. Figure 1 below shows the change in income that households would experience by filing status, number of children, and income.

Romney’s proposal is most generous for the very poor. This is as expected: it replaces a “phase-in” for the CTC with a flat child allowance. Whether that might discourage work is discussed more below.

But what you can see is that married filers benefit at all income levels. For single (or, where eligible, head of household) filers, there’s more variety. Most non-married filers come out about even with their current benefits. The only parts of Romney’s proposal I have not incorporated in this model are 1) a small change to categorical eligibility for SNAP (food stamps) and 2) the SALT deduction, which mostly effects high earners and of course varies widely by state, 3) the child and dependent care deduction, which also mostly effects higher earners, and I don’t include because claiming it isn’t directly related to income. Changes in these programs are much smaller than the changes to the CTC, EITC, Head of Household status, and TANF, which I have modeled.

Who benefits from Romney’s plan? Most people. The benefits are largest for families with three or more kids, but even many childless households stand to benefit. There are some small losses for single parents who currently reap disproportionate benefits from the current system, but among the very poorest single parents, the benefits are quite large.

Marriage Penalties

Now that we know who benefits, it’s possible to ask what effects this proposal might offer. One of the most important possible effects of a reform like this is on marriage. Will this reform make it harder for people to get married, or easier?

Many people who receive welfare benefits avoid marriage because getting married will cause them to lose their benefits. This is a significant problem. By eliminating TANF (one such program), Romney’s plan removes a whole set of marriage disincentives directly. But reforming the EITC also reduces marriage penalties.

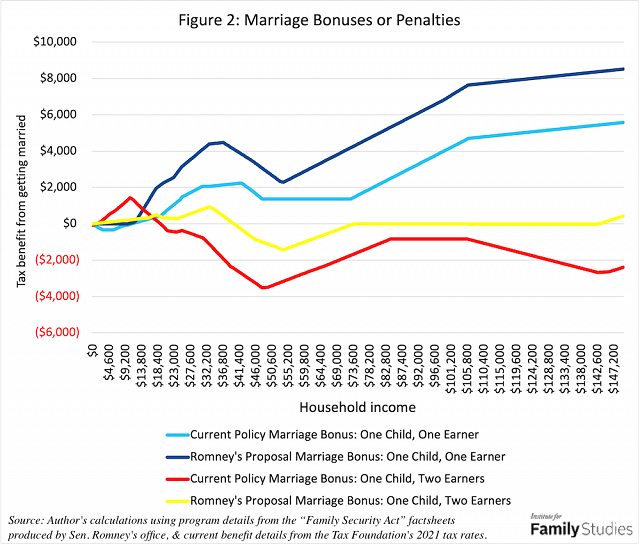

However, marriage penalties are complicated to calculate. Imagine a couple with one child, where one member of the couple works and the other does not. If they get married, their joint income is the same as the one worker’s individual income. The brackets may change in their favor (income tax brackets double for married people), giving them a “marriage bonus,” though other eligibility rules for various credits and programs may have other effects. Which effect will predominate is hard to say.

On the other hand, consider a couple with one child, where each partner earns half of the income. They might both individually be eligible for various benefits and credits, but when they get married, their combined income may make them ineligible as they exceed eligibility thresholds for various programs, since while tax brackets usually double with marriage, credits and welfare programs eligibility thresholds often do not.

To test how Romney’s plan influences these effects, I calculate marriage penalties for one-earner and two-earner households with one child across the income spectrum, both as single/head of household filers, and then the same couple as joint filers, to see how joint filing changed their income net of taxes and benefits under current policy vs. Romney’s proposal.

Under current policies, there is a small marriage penalty for one-earner households making under $11,000 per year. That means, even in households where one partner earns all the money, current policies make staying unmarried the most advantageous tax arrangement when income is below $11,000. Romney’s proposal eliminates that penalty: at no point does Romney’s plan ever penalize one-earner households for choosing to get married. And beyond that low threshold, the tax benefits to marriage are increased across the entire income spectrum for one-earner households.

Two-earner households have a more complicated story. Current policies actually provide a small marriage bonus to low-income, two-earner households thanks to the limits on refundability of the CTC. But those benefits don’t last, and marriage penalties under the current tax code quickly get very large. Just considering a few provisions, under the current tax code, some two-earner families could lose nearly a tenth of their income from getting married, and marriage remains tax-disadvantageous throughout the income spectrum. The simple reality is, under the current tax code, in families with children and two similar-income adult workers, it is almost always better for one adult to file as “single” and the other to file as “head of household.” This is absurd, but it’s reality: and my guess is most of us can immediately think of a couple who is doing precisely this calculation.

Romney’s proposal does not completely fix marriage penalties; there’s just too much stuff going on in the tax code for one proposal to do that. But it does dramatically reduce those penalties, and for households making under $40,000, it actually provides a small marriage bonus. This gives more equitable treatment to married couples, especially two-earner couples.

Romney’s proposal will not create more single parents but do quite the opposite. It will remove huge marriage penalties and create or expand marriage bonuses. Far from subsidizing single parenthood, this proposal would actually move the tax code towards a more marriage-friendly position.

Work Effects

Aside from marriage, it’s also reasonable to ask how this child allowance might impact work.

Two quick points are important: first, Romney’s proposal does not create any benefit cliffs. There’s no point at which Romney’s proposal puts a person in a position where earning extra money causes them to lose money overall. It does not create poverty traps of that kind, as many welfare policies do.

Second, the same graph I showed of marriage penalties has another interpretation. If a two-earner couple is penalized for getting married, that also mathematically implies that within a two-earner married couple, the lower-earning spouse is being penalized for working. These are deterministically linked statements: two-earner marriage penalties can also be phrased as marriage-related earner-penalties. By reducing marriage penalties, Romney’s proposal increases the work incentives facing lower-earning spouses.

But when conservatives ask how a child allowance would impact work, these concerns aren’t what we have in mind. The real effect we have in mind is related to “reservation wages” and the “income effect.”

Reservation wages are a concept that says people have a specific wage in their mind, and they strongly dislike working for less than that wage. For most people, some pay rate is too low to justify the trouble of going to work.

Income effects relate to how peoples’ behavior changes in response to having more income. As it relates to work, this means that as people have more income, they may desire to work less, because their immediate, pressing needs have been satisfied.

Child allowances impact both of these concepts. Child allowances boost how much income people have even without working, which results in less pressing economic needs and which may cause them to desire to work less. That, in turn, raises their reservation wage, with the result being fewer people working for any given prevailing wage rate.

So, based on these concerns, child allowances will reduce labor force participation, contrary to the marriage penalty issue I described above. And indeed, when Poland rolled out a child allowance in 2016, mothers’ labor force participation did decline.

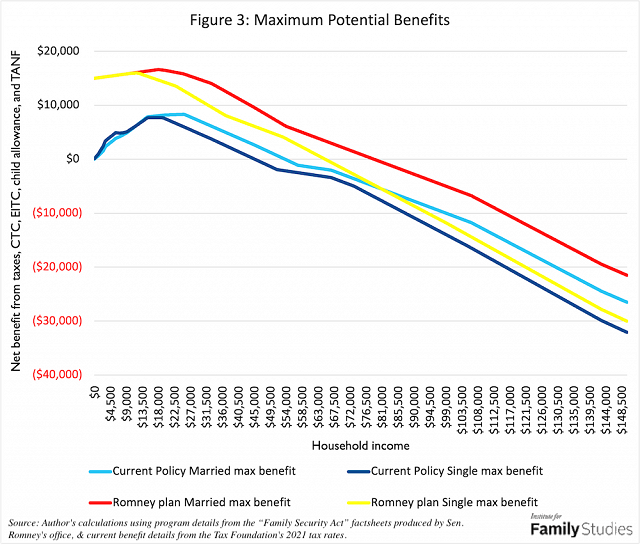

But will this happen in the case of Romney’s plan? We can look at this in several ways. One way is to ask, “What is the maximum public benefit provided under Romney’s plan vs. the status quo?” This will show us if Romney’s plan actually increases the total amount of public support a person could theoretically get.

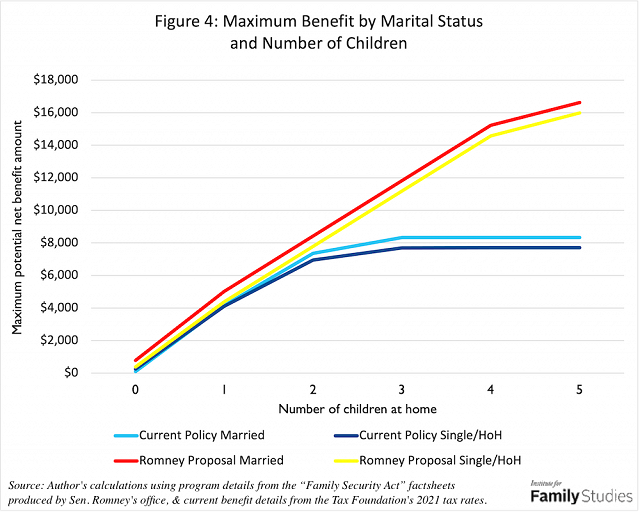

The theoretical maximum benefit that could be received among married or single/head of household filers with between 0 and 5 children at home is indeed larger under Romney’s plan. In principle, this could lead to the kind of income effect conservatives worry about: people deciding the dole is better than work.

But it’s important to understand how those maximum benefits arise. Under current policies, the maximum benefit (i.e., the largest absolute difference between earned income and post-tax, post-benefit income) that can be obtained is by having three kids and earning $25,000 a year. Under Romney’s proposal, the maximum benefit is larger, but to obtain it, you’d have to have 5 kids and earn $18,000 a year. Figure 4 shows the maximum benefit available by number of children. The income threshold for peak benefits is a bit lower in Romney’s plan, but still is nowhere near zero. And getting that benefit involves considerably more children.

Which of these is more likely to occur? Well, we can use survey data to check. About 300,000 households have 3 kids at home, and wage and salary income between $24,000 and $26,000. Meanwhile, there are only about 22,000 households with wage and salary income between $17,000 and $19,000 and with five kids at home. There are about 50-60 million households with children in them in the U.S., so I think 0.042% of women receiving unusually high benefits is perhaps not a major social crisis. The aggregate labor effects of this are quite small.

Meanwhile, for the vast majority of people living in households with between 0 to 2 kids, the maximum possible benefit under Romney’s plan is only slightly higher than current policy. The potential for so-called “welfare queens” to abuse the system is not much greater than under the current system, and the labor market effects of such behavior would be very small.

Thus, while we can’t unambiguously say how this proposal would alter labor force participation, it does not seem likely that it would cause any large work disincentives. There might be a few people who shift out of market labor, but the effects will be extremely modest.

And beyond being modest, that shift out of work may even be beneficial. The reality is that if a person has to choose between driving an Uber or taking care of their four-year-old, society and that child is probably better off with a little more parent-child time and a little less time at work. Our society has a critical problem with broken families and absent parents that desperately need a serious attempt at a solution. Romney’s child allowance supports stable, married life; it alleviates the deep poverty that crushes many children’s opportunity for economic mobility; and it does not create new obstacles to work for low-income families. All while being deficit neutral.

But the more threatening deficit in our society is a deficit of parenting. The worthy and honorable work of raising children should not be treated as an inferior good, as something policymakers would happily swap for a few more hours sorting packages at an Amazon warehouse. If the result of providing a child allowance is that some parents choose to stay home with their young children, have more meals together, go to more parent-teacher conferences, or actually do evening prayers together without rushing through them, that’s not a loss for society, the child, or the parent. Giving parents cash to enable them to make choices about how to support their family is a valuable task, especially when that money only barely offsets other government-induced costs, be they marriage penalties or car seat laws.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a market forecaster for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or viewpoint of the Institute for Family Studies.