Highlights

- Working class couples often have the mindset Pakaluk describes as necessary for a revival of the birthrate, but not the means (money and marriage) to do so. Post This

- “Family first,” as one woman put it, is an apt summary of a common working-class mindset. Post This

- Working-class adults often have pro-family values that are in tension with material limits, stresses, and relational insecurities. Post This

Last year, in the middle of a snowstorm on Christmas Eve, I became a mother of six at the age of 35. So it was with great interest that I read Catherine Pakaluk’s recent essay on falling birthrates, in which she draws on interviews with college-educated mothers of five or more kids. I was moved by the piece, seeing in these mothers the contours of my own identity transformation, and resonating with their hard-earned wisdom.

And yet, because of my own qualitative research with mostly non-college educated young adults in Ohio over the past decade, I found myself questioning the logic of Pakaluk’s critique of pronatal policies. Pakaluk argues that such policies are misguided because so many of the costs of childbearing are immaterial and the driving motivations transcendent.

She draws on interviews with mothers of large families to argue that “falling birth rates are not a cost problem, at least not in the way we normally think about a cost problem.” Pronatal policy doesn’t work, she writes, because “[c]ash incentives can’t answer what needs to be answered: a reason to give up dreams and aspirations that can’t hang on past one or two kids.” In order to choose to have more children, women must have transcendent reasons to value family over and above the personal subjective costs to themselves and their careers. She concludes:

But right now, whatever the difficulties, there are women in every state in the nation having abundant families against the norm. They don’t do it because they face lower costs—they live in the same world as we do. They do it because it’s worth so much to them. We won’t have more babies until more women think about children the way Leah does, ‘valuing children first. The family unit being the priority above career and personal identity.’

In a highly educated context, this certainly may be true. But is it equally true for the nearly 70 percent of Americans without college degrees? A different picture emerges when I think about the working-class young adults I know, who often inherit a script that values family as life’s primary meaning maker and whose identities are not tightly bound to education or work.

I deeply appreciate how Pakaluk’s qualitative work draws attention to the reality that the decision to have a child is not merely or even primarily a financial one. But she overlooks members of the working class, who often have the mindset Pakaluk describes as necessary for a revival of the birthrate, but not the means (money and marriage) to do so—and for whom a child allowance or other benefit could make a modest but significant difference.

"Family First"

In the summer of 2010, my husband David and I began interviewing young adults in a small Ohio town in the hopes of better understanding the class-based marriage gap about which scholars like Brad Wilcox and Charles Murray were writing. As a 23-year-old fresh out of college, I remember being surprised by the abundance of unabashedly family-oriented attitudes we found.

As one 19-year-old-woman told me,

I was reading in Cosmo, this girl, she said from a young age [that] she’d never wanted kids. And she was 38 and still doesn’t want kids. And it’s like, okay, I understand where you’re coming from, but you’re crazy! Because that’s kind of the biggest point in life. More than falling in love, more than your house, more than your money, more than anything is keeping your family alive, keeping the world going. That’s what you’re put on this earth to do.

She told me if she could get some financial aid, she hoped to go to college as soon as possible, hoped to be married by 25, and hoped to start having kids by age 28. She thought 30 would be too old. This timeline was a bit unusual among our interviewees, many of whom became parents in their early twenties and echoed sentiments like 22-year-old Cassie, who was pregnant when she said, “[Children are] a huge blessing. That’s why I want one…. I’ve always wanted kids, ever since we got out of high school…. I always knew that if I stayed here, I would be a mom…. [sooner] than if I went to college.”

“Family first,” as one woman put it, is an apt summary of a common working-class mindset.

Chris, a 22-year-old welder when we first spoke with him in 2010, was dumbfounded when asked about the rise of childless adults:

I don't understand why you wouldn’t want to have a child. So that’s kind of a hard question for me to answer. I really don't know…for me, I consider marriage and starting a family. I don't see a marriage as just me and my girlfriend the rest of our lives without a child. I've been brought up that it’s a good thing to have a kid if you’re financially stable to have it. And I've always wanted one. I just don't understand why married couples wouldn’t want to have a kid. Fatherhood is something that I'm looking forward to.

His description of the meaning of fatherhood mirrors the language of sacrifice and accomplishment that Pakaluk’s interviewees used. He imagined that parenthood would be “more hectic” and “a giant responsibility financially” and that it would “take up more time—sleepless nights, things like that” but concluded,

But it’s all worth it in the end knowing that you brought forth into the world a child that you can call your own, watch them grow up is one of the happiest things you can do, one of the best things you can…. when they are old enough to grow up and get married on their own and be able to watch them walk down the aisle and watch them get married - it gives you that sense of pride. It gives you that sense that, ‘I did this. Look at what I've accomplished.’ And that’s the main reason why I'm looking forward to being a father. I mean, it’s worth it in the end regardless of what you have to do.

There’s evidence to suggest that the story of declining fertility in America, and indeed around the world, is not about people losing the desire for children. On the whole, American women are having fewer children than they say they want.

But if not desire, what then is keeping people from their stated ideals?

"A Lot of Factors"

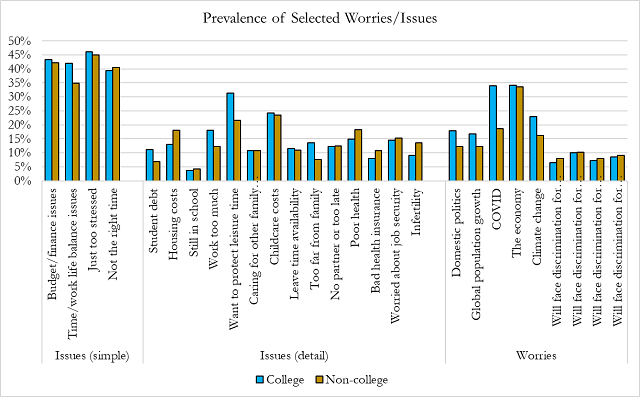

Surveys suggest a smattering of factors, with no one thing rising to the top as the only answer. Financial issues, time and work/life balance issues, health, and stress are all reported. Though answers are generally similar across class lines, there are some interesting differences. In one data set of 10,000 respondents ages 25-44, pictured below, college-educated respondents were more likely to say that time and work/life balance issues—things like wanting to protect leisure time, working too much, and being too far from family—impacted their family plans. Non-college-educated respondents were more likely to name housing costs and bad health insurance, poor health, and infertility as barriers to fertility.

Recently I spoke with Tonya, a 34-year-old stay-at-home mom who is raising seven children in a double-wide trailer with her husband, a utilities locator. When I asked her about fertility decline, she mentioned inflation, housing costs, and the opioid epidemic. She talked about cultural change like how today people are “more accepting” of different lifestyles. She also mentioned friends struggling with infertility “because of their surroundings, or medications they’re taking.” (Which is something I heard from multiple women, unprompted by me. “I’m not a crunchy, hippie mom. I go to McDonald’s all the time,” a 30-year-old mother of twins told me. “But there’s got to be something in our environment, the food we eat.”).

Tonya also talked about a decline in community support. “When I was young, the [extended] family was a community that helped raise each other. But today grandparents don’t want to be grandparents…. I wish the community could be a community again.”

A Broken Heart Problem

The first thing Tonya mentioned, though, was relational instability. “More people aren’t in committed relationships when they choose to have kids,” she said, “so they have a kid with one person, and then they have a kid with another person, and then they’re done because they don’t want to raise kids on their own.”

Tonya and her husband started dating when they were ages 13 and 14 and got married shortly after high school. Originally, they talked about having just one or two kids; the number of children they have had is in part a function of the fact that, as Tonya put it, “We’ve been together so long.”

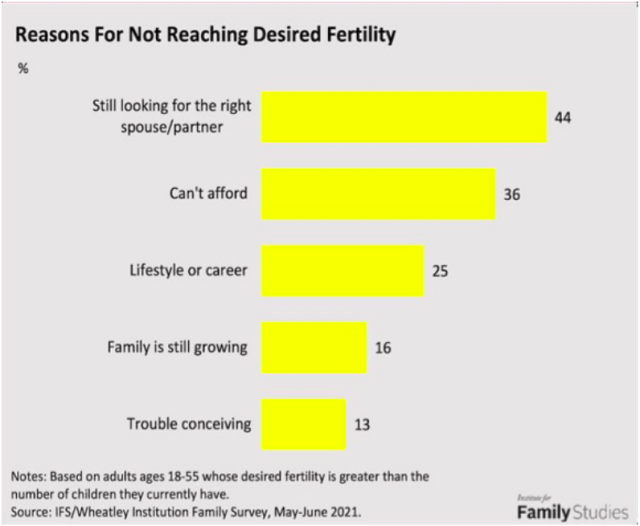

Indeed, evidence suggests that marriage rates and timing play a key part in the story of fertility decline. A 2022 IFS research brief reported that the top reason given for not reaching desired fertility is “still looking for the right partner.”

Interviewees that I first met in 2010 who talked about children as life’s priority and biggest blessing today have fewer children than they would have liked. Cassie, quoted earlier, has been divorced twice and subsequently never had more than one child. Chris, the welder who waxed eloquent about fatherhood, did have a baby girl in 2015. “No matter how much money or how little I have, I'll always be rich cause of her,” he wrote. But he is no longer with the mother of his daughter. “Why is trying to find oneself so difficult?” he asked recently on Facebook.

I am reminded of how Pakaluk poignantly describes falling birthrates as a “broken heart” problem. And I agree with her that religious institutions can lead the way here. Efforts like Communio come to mind, or the way some young adults instinctively reach out to churches for help in times of crisis. (And childless adults who are religious are more likely to say they want children.) In matters of the heart, religious and civil society institutions that build trust with young adults at the local level will do a better job at being responsive to unique people and finding creative solutions.

A Broken System

But fertility decline is also a broken system problem. In the chart above, the second biggest reason given for not reaching desired fertility is “can’t afford” (ahead of “lifestyle and career”). Given this, it makes sense that measures to assist families financially would have some effect on fertility. This same research brief reports that,

Nearly half of parents who desire more children (49%) and 43% of childless adults who want children say that a child allowance, such as $300 per child per month, will make them more likely to have children. Even among the childless adults who desire no children, 12% indicate that their likelihood of having a child will increase if a child allowance were provided.

Contrary to Pakaluk’s assertion that cash to families “hasn’t worked anywhere it’s been tried,” results around the globe are mixed but not conclusive. As always in policymaking, the devil is in the details, but it seems possible to propose family policy that is at once pro-work, pro-marriage, and aligned with American values and traditions.

Housing is also on Tonya’s mind. Her family’s mobile home park recently transitioned to becoming a 55 and older park, which is just one example of burdens families with children face in the housing market. After searching for months, Tonya and her husband can’t find anything affordable that meets occupancy standards, and she perceives that “people don’t want to rent to us because we have so many kids.” (Indeed, housing discrimination based on familial status was the fourth common type of complaint filed with nonprofit fair housing organizations and government agencies in 2021.) Costs of moving their double wide are prohibitive but they will lose money on it if they sell it. They’re currently thinking of trying to find a place with her brother and his family so that they can have four adults sharing the work of childcare and the costs of housing instead of two.

Data suggests a correlation between high rent and lower fertility, as well as negative effects of land use restrictions on fertility. While Tonya is remarkable in that she has welcomed a big family despite these conditions, it’s easy to see why others would not.

Indeed, Tonya is like the women Pakaluk interviewed in that she sees having a big family as “epic,” and thinks the good of children outweighs the significant personal costs. Tonya and her husband didn’t set out to have a big family, necessarily—but throughout our conversation, Tonya repeated the phrase, “family first.” One of their children was adopted after his mother, an extended family member, died of an overdose. Two others are nieces who needed a more stable environment. Their mindset with each child has been, “Okay, this is going to change things. We’ll work through it.”

Other working-class families I know have a similar attitude. Perhaps this is why the non-college educated childless respondents were slightly less likely to cite budget issues as affecting their family plans. Lindy, a mother of three whose husband grew up in foster care and at first didn’t want children of his own, told me that by having children they’ve chosen a simple but rich life—catching crawdads, cooking, and bike rides. She says of the rich, “all that money is not worth the life [you’re missing].” One example of the tradeoffs they’ve made is that instead of having a wedding, they went to the justice of the peace, because it was more important to use that money for housing and necessities for their kids.

The difference when a college-educated person adopts this open-to-children mindset is that the costs are real but likely less risky. It may require moving to “a less than pleasant part of town,” an example one interviewee gave me, or changing spending or leisure habits or career goals. For working-class families, the risks of having more children include poverty: not being able to pay basic bills, stressing to feed the family, and facing foreclosure or eviction. A Pew survey last year found that 1 in 4 parents struggled to afford food or housing. An American Compass survey on family affordability released earlier this year found that “parents with income of $40-60K were as likely to worry about affording health insurance, a home, a car, nutritious food, or college tuition as parents with income below $20K.”

In interviews, working-class respondents told me they’d like to be “financially set” before kids—by which they typically meant a basic standard of being able to pay rent and for basic necessities—but they feel increasingly squeezed by the costs of living, especially by the costs of housing, transportation, childcare, and healthcare. Holly said that while some people don’t prioritize kids, with “the economy being so bad” others “just don’t have the money.”

Chris, the welder, recounted conversations he and his girlfriend had about whether or not to have a baby. It’s a fascinating illustration of the deep desire to have children, as well as the negotiations that take place over which standards of material stability ought to be in place before having children.

She still has that spit and vinegar attitude to her, that, ‘I can do whatever the heck I want’ attitude. She has a very unstable job…. she's bouncing around from house to house…. And I don't think she's ready. She says she is, but I'm saying no. Like, ‘I can barely support myself so what makes you think I can support the child?’…. I've seen relationships fail— like catastrophically fail because of stuff like this.’ And she agreed to an extent.

In other words, working-class adults often have pro-family values that are in tension with material limits, stresses, and relational insecurities. They share an expectation of financial stability before kids, but it’s a fairly basic and prudent standard. Even so, the working class are more willing to bend here, to fudge standards, to make it work—sometimes because even a basic standard of stability feels out of reach. Their fertility choices involve wrestling with tradeoffs that more affluent people don’t have to make.

It’s in circumstances like these that family policy—including some kind of cash benefit to working families, Medicaid expansion as a pro-life measure, and better housing policy—could be an act of justice.

Amber Lapp is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies and co-investigator of the Love and Marriage in Middle America Project, a qualitative research inquiry into how white, working-class young adults form families and think about marriage.

Editor’s Note: This essay was first published at Fusion, and it is reprinted here with permission.