Highlights

- In nearly every measure, faith-based participants showed a greater likelihood of marital satisfaction than their secular counterparts, and, in some cases, were twice or even four times more likely to have expressed satisfaction regarding an individual theme. Post This

- These findings highlight the need to implement programs and strategies to help new parents navigate this unique and critical timeframe known to influence individual and marital well-being and family stability. Post This

Whenever I am booked for a speaking engagement to a group of women, I generally arrive a good half-hour early to watch the women walk in, grab a cup of coffee, and meander to a seat. They mingle, a luxury I allow them, careful not to impose on the pre-program fellowship I know they value. Most often, I am the program—the speaker invited to impart wisdom on the topic of “marriage in the early parenting years.” Although I certainly do not have all the answers, I draw from nearly three decades of research I’ve done on this topic.

I expect similarities among the women: they will be half my age, mothers of infants or preschoolers, or expecting a baby soon. Most will be smiling brightly, chattering without restraint, and eager to learn.

I’ll also have a composite of the group and their marriages, for most will have submitted, via email, demographic information and, most importantly, their responses to a simple survey that indicates, by circling a “yes” or “no,” their satisfaction regarding themes known to influence the marriage of new parents.

I’ll wonder, as I watch, which woman stated she no longer loves her husband—or which one (if not her) is considering divorce, for there’s usually one or two among them. And which of the women, I’ll question silently, has scribbled in the margin of the survey, “Help me!”

I cherish these surveys, now stowed in boxes in my basement, their numbers swelling to the thousands. Simple and straightforward, they offer a window into the homes and hearts of new mothers and confirm firsthand what scholarly research reports: having a baby is indeed a joyous occasion for most new parents, yet the changes and necessary adjustment it brings often strain many marriages, sometimes resulting in a stress-filled, dissatisfying union.1

My 2013 paper, Assessment of Marital Satisfaction & Change In Early Parenting Years, summarizes a random subset of 1,074 mothers who submitted surveys measuring these marriage-defining themes between 1997 and 2013. The findings are drawn from two distinct populations that have been my decades’ long focus of education, which I refer to as Group A (faith-based/religious) and Group B (secular).2

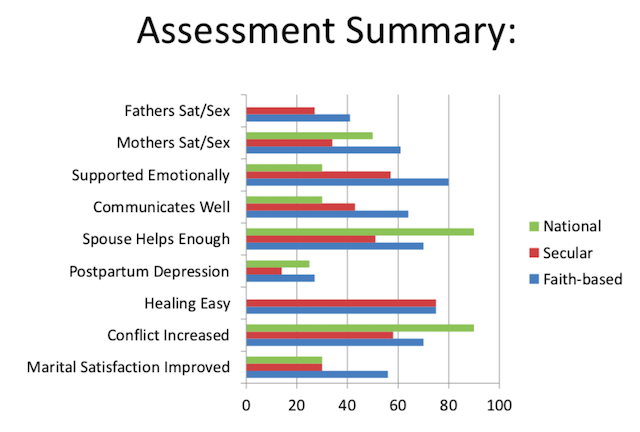

I did not intend to compare the two populations of mothers; however, the differences in survey results were striking. In nearly every measure, faith-based participants showed a greater likelihood of marital satisfaction than their secular counterparts, and, in some cases, were twice or even four times more likely to have expressed satisfaction regarding an individual theme. They were also 40% less likely to have considered divorce and more likely to have sought help with their marriage and find it beneficial.

Mothers within the faith-community were nearly twice as likely to report that “marriage improved after becoming parents” than their secular counterparts; however, they were also approximately 20% more likely to report increased marital conflict. (Subsequent survey results, however, not included in the assessment, contradicted this analysis.)

A variation between the two groups was most evident regarding the sexual relationship of new parents: mothers from the faith-based group were twice as likely to report satisfaction with their own sexual relationship, and in some cases, four times more likely to state that their husbands were satisfied too, compared to mothers in the secular group. Specifically, 61% of the mothers from the faith community were satisfied with their sexual relationship, verses 34% of the secular mothers, and 41% of faith-based mothers reported her spouse was satisfied with his sexual relationship, verses 27% of the secular.

Two factors may have influenced the differences in survey results: the type of community hosting the education seminar (was it faith-based or secular?); and the rate of the mothers’ workforce participation.

Women in Group A (faith-based, who comprised 85%, the vast majority of my respondents) attended education offered by various women’s ministries and therefore may have had the advantage of faith that is known to contribute to outcomes of increased family satisfaction. They may also have possessed personal qualities that positively affect relationship well-being.3 Sixty-five percent of the faith-based mothers reported “praying for her spouse,” and 54% said that they “prayed for their marriage.”

Women in Group B (secular, who represented 15% of my respondents) participated in education sponsored by schools, community organizations, corporate wellness, and health care institutions. I cannot say that prayer did not influence the observations of my secular mothers because they were not asked about prayer habits or faith-orientation, nor can I say that these mothers did not possess similar personal qualities.

By the time children enter school, most parents will have weathered the early stages of relationship imbalance and find their marriages (with children) to be more stable, enduring, and contented.

Could it also be that the faith-based mothers were more likely to report satisfaction regarding individual themes because of their low rate of workforce participation? Mothers from the faith-based group had half the rate of workforce participation as women in the secular group; and if working outside the home, these mothers were three times more likely working part-time than full-time, thus being spared work-related stress that often increases relationship strain and decreases warmth and support in marital interactions—despite the faith orientation within the home.4

A number of other factors lead me to believe that this assessment represents a “best-case scenario.” First, the mothers who provided survey results were exposed to fewer risks to marital and relationship well-being than mothers in the at-large population, as participants were voluntary, almost all were white and married, lived in households where at least one spouse was employed, and had (or took) the opportunity to attend education that focused on family well-being (indicating that the women valued marriage, family, and/or community connections). Few will argue that these factors do not paint a best-case scenario for reducing risks to marital and partner satisfaction.5

I hesitate to make broad generalizations about a population of 1,074 mothers who took a survey that was not scientifically designed, nor do I pass judgment on the results. Nonetheless, I captured raw numbers of mothers from both surveyed communities that report increased marital conflict after becoming parents and low rates of marital satisfaction along individual themes. These surveys represent a mere snapshot of the history of those families. I’d like to emphasize, too, that for most couples, having a baby brings positive change and offers opportunities for growth and a deepening of the marital bond. By the time children enter school, most parents will have weathered the early stages of relationship imbalance and find their marriages (with children) to be more stable, enduring, and contented.6 I found this to be true in my own marriage as well as for countless other parents I interviewed in ensuing decades.

Even so, mothers from both groups reported increased marital conflict after becoming parents and reported low rates of satisfaction regarding individual themes known to contribute to or detract from marital and relationship satisfaction during the early parenting years. These findings highlight the need to implement programs and strategies to help new parents navigate this unique and critical timeframe known to influence individual and marital well-being and family stability.

Rhonda Kruse Nordin researches and writes on family issues and is a senior fellow with the Center of the American Experiment.

1. Gottman, J. M, & C.I. Notarius.(2002). “Marital Research in the 20th Century and a Research Agenda for the 21st Century.” Family Process 41:159-197; Hackel, L.S., & Ruble, D.N. (1992). Changes in the marital relationship after the first baby is born: Predicting the impact of expectancy disconfirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 944-957; Kalmuss, D., Davidson, A & L. Cushman (1992). “Parenting expectations, experiences and adjustment to parenthood: A test of the violated expectations framework,” Journal of Marriage and Family54: 516-26; Schulz, M.S., Cowan, C.P., & Cowan, P.A. (2006). “Promoting healthy beginnings: A randomized controlled trial of a preventive intervention to preserve marital quality during the transition to parenthood,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 20-31; Belsky, J.; Lang, M. E.; and Rovine, M. (1985). "Stability and Change in Marriage Across the Transition to Parenthood: A Second Study," Journal of Marriage and the Family47:855–865.

2. The “Assessment of Marital Satisfaction and Change in Early Parenting Years” by Rhonda Kruse Nordin was housed in the Work Family Researchers Network (WFRN) repository of information, School of Sociology (SAS), University of Pennsylvania, now at Cornell University. Founded in 1997, the Work and Family Researchers Network serves as the premier online destination for work and family scholarship. My paper was accepted for a workshop at their 2013 and 2014 WFRN conferences. For a PDF copy of this paper, please contact the author at: rhondanordin@aol.com

3. Fincham, F.D., Stanley, S. M., & Beach, S.R.H. (2007). “Transformative processes in marriage: An analysis of emerging trends,” Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 275-293. Also: Durkheim, Emile, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life(New York, NY: Free Press, 1965). And: Heaton, T.B. (2002). “Factors contributing to increasing marital stability in the U.S.,” Journal of Family Issues, 23, pg. 392. And: White, Lynn and Stacy J. Rogers. 2000. “Economic Circumstances and Family Outcomes: A Review of the 1990s,” Journal of Marriage and the Family. 62: 1035-1051.

4. Page 28 of my report. See also: Matthews, L.S., R.D. Conger, and K.A.S. Wickrama. (1996). “Work-Family Conflict and Marital Quality: Mediating Processes,” Social Psychological Quarterly. 59:62-97.

5. White, Lynn and Stacy J. Rogers. 2000. “Economic Circumstances and Family Outcomes: A Review of the 1990s,” Journal of Marriage and the Family. 62: 1035-1051.

6. Sollie, D.L. & Brent C. Miller (1980). “Normal stresses during the transition to parenthood,” Family Relations(29), 459-65.