Highlights

- As a society, we care about these two groups of men because their actions or inactions have a sizable impact on the development and well-being of millions of children. Post This

- Having responsibility for a child helps many men become more mature and spurs them on to work harder at their current job or seek more gainful employment. Post This

When Father’s Day rolls around, there are two sizable groups of American fathers who do not receive much attention in the popular media or from greeting card manufacturers. One consists of fathers who live with their children, but not with the kids’ mothers—or single, custodial fathers. The other consists of fathers who live apart from their children, or non-resident fathers. In the past, these situations were usually due to the death of a parent. Nowadays, they are usually the result of separation, divorce, or non-marriage. The terms used to label these men grow out of divorce proceedings and family court and have a legalistic and pejorative tone. Men in the former group are typically called, “custodial fathers,” which sounds more janitorial than kindly and caring. Those in the latter group are variously labeled “absent fathers,” “non-residential fathers,” or even, by some, “deadbeat dads.” For the present purpose, I will call them “non-custodial fathers,” even though nearly a quarter of them share joint custody of their children with the mothers with whom those children usually reside.

As a society, we care about these two groups of men because their actions or inactions have a sizable impact on the development and well-being of millions of children. In its most recent report on child support, the Census Bureau tells us that in 2018, nearly 22 million American children had a parent who lived outside their household, and that these children represented more than one-fourth of all children under 21 years of age.1 The poverty rate for these children was about three times higher than it was for children in households with both parents present. Almost half of all black children had a parent who resided outside the household in which the child lived.

The Census report provides a good deal of information about custodial fathers, such as their age, educational attainment, racial and ethnic background, and work history in 2017. But it furnishes none of this information about non-residential fathers, those dads who lived apart from their children—not even their exact number. We can infer some things about these men, however, from the information that the report provides about custodial mothers. The following research brief provides a comparative profile of custodial and non-custodial fathers based on what the Census tables do tell us.

Comparative Demographics

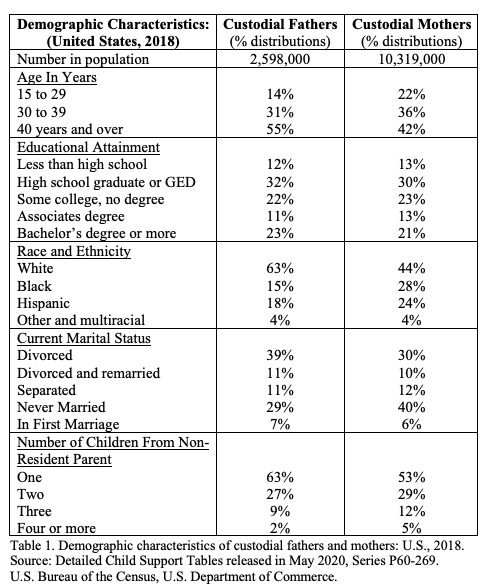

There are fewer custodial than non-custodial fathers. There were 2.6 million of the former in 2018, taking care of nearly 4 million children whose mothers lived elsewhere (see Appendix Table). By comparison, there were 10.3 million custodial mothers, caring for almost 18 million children whose fathers lived elsewhere. Custodial fathers represent less than 8% of all fathers living with children in the U.S., whereas custodial mothers represent about 25% of all mothers living with children.2

Custodial fathers tend to be older and more educated than non-custodial fathers. A 2013 study based on the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth found that a 63% majority of fathers living apart from their children had a high school education or less, whereas a 51% majority of fathers living with their children had some college education or more.3 Nearly two-thirds of custodial fathers are white, whereas 52% of custodial mothers are black or Hispanic. More custodial fathers became lone fathers as a result of divorce, whereas more non-custodial fathers became absent fathers subsequent to unmarried births.4 Non-custodial dads are the presumptive or verified fathers of slightly more children than custodial dads (mean of 1.73 versus 1.53 children).

Relationship With Mothers of Their Children

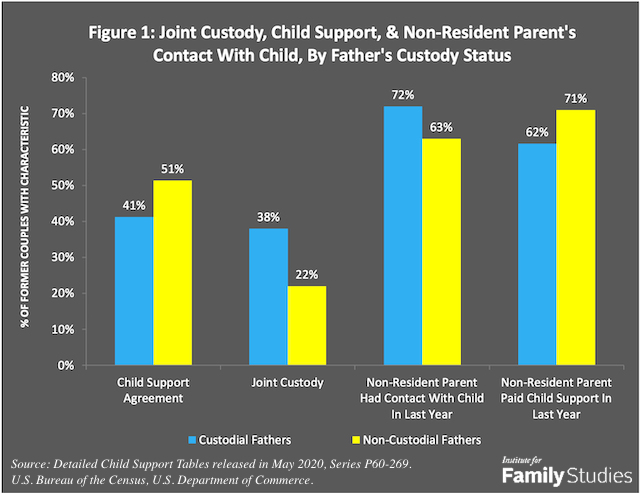

As shown in Figure 1, more non-custodial fathers had child support agreements with their former mates than did custodial fathers. On the other hand, fewer had joint custody of their offspring than custodial fathers did with the mothers of their children. Nearly two-thirds of non-custodial fathers had at least limited, in-person interaction with their child, as did nearly three-quarters of non-custodial mothers.

Based only on former couples who had child support agreements, agreements in which the custodial parent was supposed to receive support payments in 2017, 71% of non-custodial fathers and 62% of non-custodial mothers paid at least some support in that year.5 The average (mean) amounts received by those residential parents who received any support were meager in both instances: $4,913 by custodial mothers and $4,908 by custodial fathers.

Financial Well-being of Families in Which Their Children Live

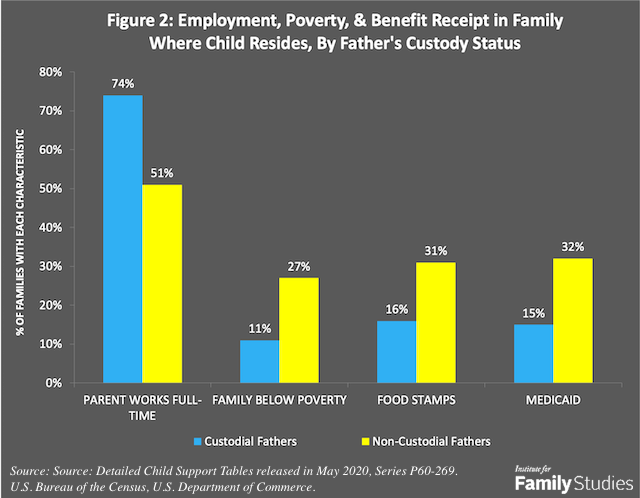

As shown in Figure 2 below, nearly three-fourths of custodial fathers worked full-time throughout the year 2017. The same was true of just over half of custodial mothers (not shown). Nine percent of custodial fathers did not work at any point in the year, whereas the same was true of 22% of custodial mothers. The Census tables do not provide information about the employment histories of non-custodial fathers during the same year. But we can infer from the reasons that custodial mothers gave for not seeking child support awards that many non-custodial parents were employed only sporadically or at low-wage jobs.6

The mean personal income of custodial fathers in 2017 was $56,255. The comparable income of custodial mothers was only about 60% as much: $32,917. By comparison, the median personal earnings of all married fathers who lived with their children was $60,826 and the median personal earnings of all married mothers who lived with their children was $37,846.7 Sum those two figures and you get 1.75 times the average income of custodial fathers and two times the average income of custodial mothers.

The family poverty rate for children of non-custodial fathers was 2.4 times higher than the comparable rate for children of custodial fathers, as may be seen in Figure 2 above. Children not living with their fathers were more likely to be participating in one or more government assistance programs than were families of custodial fathers. Families of custodial fathers were only half as likely to be getting Food Stamps or receiving medical care paid for by Medicaid.

Questions To Ask On Father’s Day

This comparison of custodial and non-custodial dads shows that a majority of men in both groups are making efforts to live up to the role of father. Custodial single fathers are doing quite a lot: they reside with and care for their children in the absence of the children’s mothers. Most of these dads work full-time throughout the year and earn enough to keep the family out of poverty and not dependent on government assistance. Although their children receive less attention from their mothers than they would if they were living with mom, most have at least some contact with her during the year. Nearly 40% of custodial fathers have a joint custody arrangement with the mother.

Men in the much larger group of non-custodial fathers are doing (or being allowed to do) less. Just over half have a child support agreement and the majority of those with such agreements paid some support during the year. But less than a third of all non-custodial dads made any support payments. Nearly two-thirds had at least some contact with their children during the year, while less than a quarter have a joint custody arrangement with the mother. The economic well-being of the families in which their children are growing up is considerably worse than that of custodial fathers.

It is important to acknowledge that the non-custodial father population is considerably different than the custodial father population. There are more black and Hispanic men among non-custodial dads, and more whose employment and earnings prospects may not be the brightest. Unfortunately, the Office of Child Support Enforcement and the Census Bureau do not provide much information about the family living situations, educational attainment, employment or earnings of these men. So, one question to ask on Father’s Day is: Why don’t they?

Another question: Given that children who live with custodial fathers seem better off, at least financially, why aren’t more fathers given joint custody of their children following a divorce or non-marital birth? Having responsibility for a child helps many men become more mature and spurs them on to work harder at their current job or seek more gainful employment. It seems reasonable to assume that it might have similar beneficial effects on unmarried or formerly married fathers.

A great deal of statistical evidence indicates that the best thing for children’s physical, emotional and intellectual well-being is being raised by both married biological parents. In the absence of this ideal, taking steps to increase the participation and involvement of both biological parents in the care and rearing of their joint offspring still seems desirable. Current policies and practices are not showing much progress in improving the lot of children of unmarried parents. Father’s Day seems like a good time to start trying something new.

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce.

Appendix

1. Timothy Gall, Custodial Mothers and Fathers and Their Child Support: 2017. Current Population Report P60-269. U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. May 2020. With accompanying detailed tables.

2. Author’s calculation from Table A3. Parents With Coresident Children Under 18, by Living Arrangement, Sex, and Selected Characteristics: 2018. November 2019. U.S. Bureau of the Census. U.S. Department of Commerce.

3. Jo Jones & William D. Mosher. Fathers’ Involvement With Their Children: United States, 2006-2010. National Health Statistics Report No. 71, December 20, 2013. National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Table 1. The 2017 child support report also shows a 56% majority of custodial fathers having some college education or more.

4. As shown in Appendix Table 1, half of the custodial fathers were divorced or divorced and remarried, whereas the same was true of 40% of the former mates of non-custodial fathers. Conversely, 36% of the custodial fathers were never married or in their first marriages to women other than the mothers of their children, whereas 46% of the former mates of non-custodial fathers were never married or in their first marriages.

5. This is how the Office of Child Support Enforcement and the Census Bureau calculate child support payment rates.

6. Two of the leading reasons given by custodial mothers who did not seek a child support award were: “Child’s father provides what he can” (by 38%), and “Child’s father could not afford to pay” (by 28%).

7. Census Table A3. Parents With Coresident Children. See note 3 above.