Highlights

A new national coalition aimed at combatting child poverty in the United States launched last week on the heels of the Census Bureau’s release of poverty and income data for 2015. The Census report is chock-full of good news for American families, including decreases in the poverty rate for both married and single mother families, and increases in median household income—the first annual increase for family households since 2007. But, as the newly formed U.S Child Poverty Action Group pointed out, despite a drop in the child poverty rate, nearly one in five children are living below the federal poverty line.

“Despite some progress, the new poverty data paints a bleak landscape for children. Minority and young children, specifically, continue to experience higher rates of poverty than other age groups in our society,” the Child Poverty Action Group said in a statement. “Children make up 23.1 percent of the U.S. population, but account for 33.6 percent of the population living in poverty.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) also joined the call for a more targeted focus on child poverty. In its response to the Census report, the AAP lamented the fact that “children remain the poorest segment of the population,” with one pediatrician quoted as saying, “Job opportunities are clearly the greatest influence on whether children, as well as other people in the country, continue to live in poverty.”

The AAP called for “expansion of EIC, increase in the minimum wage, and assistance for families to pay for child care and housing.” According to AAP President Benard P. Dreyer, “If we did all those things, we could dramatically decrease child poverty levels.”

While better job opportunities, living wages, and government assistance for lower income families are certainly important tools for reducing child poverty, there is another weapon that is too often ignored even though it offers children the greatest protection against ever experiencing poverty—marriage. Curiously, neither the AAP nor the Child Poverty Action Group mentions the link between family structure and child poverty, even though single-parent families account for the majority of families living in poverty.

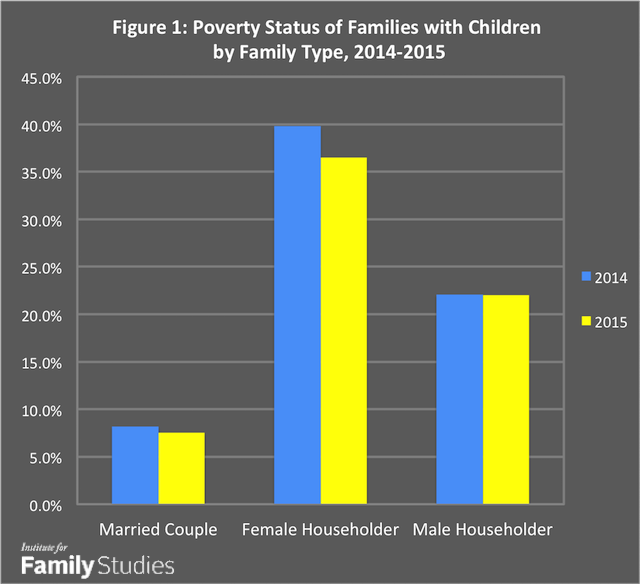

Indeed, the Census Bureau data shows that families headed by single mothers (defined in the report as “female householders with no husband present”) are over five times as likely to experience poverty as married-parent families. Figure 1 below shows the percentage of married, single mother, and single father families with children in the home in poverty. In 2015, 7.5 percent of married-couple families were in poverty, compared to 36.5 percent of single mother families, and 22.0 percent of single father families.1

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Income & Poverty in the U.S., 2015. Table 4.

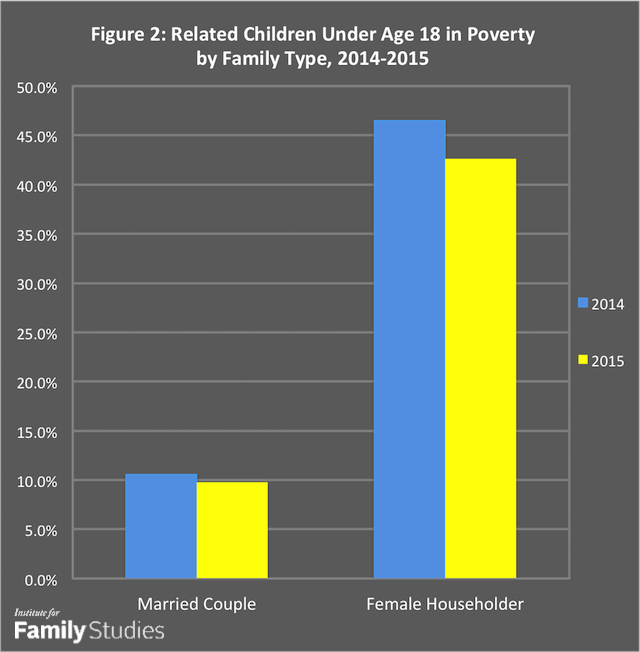

Looking specifically at poverty rates among children, once again the Census Report shows that child poverty is significantly more common for children living in single-parent families than in married-parent families. Figure 2 displays the percentage of “related children under 18” who are in poverty by family structure (note: the Census defines “related children” as “people under age 18 related to the householder by birth, marriage, or adoption, who are not themselves householders or spouses of householders”).2

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Income & Poverty in the U.S., 2015, pg. 14.

For young children in single mother families, the poverty rate is even higher. The report notes:

About half (49.5 percent) of related children under age 6 in families with a female householder were in poverty. This was more than four times the rate of their counterparts in married-couple families (10.1 percent).

A child’s family structure—whether or not a child lives with his or her married parents—is clearly a major factor in the risk of ever experiencing child poverty. If we really want to reduce child poverty, the retreat from marriage among the working class and non-college educated should concern us as much as a lack of good job opportunities. As Richard Reeves recently showed, marriage is more common among the most educated women, while nonmarital births and divorce are more common among the less educated. The retreat from marriage matters because children born to unmarried parents are more likely to experience a host of negative economic and social outcomes, including poverty.

As IFS Senior Fellow W. Bradford Wilcox has pointed out on this blog:

The math here is simple: two parents – one parent = one single parent. And, single parents, as we have seen, are much more likely to be poor than married parents….[W]e cannot lose sight of the fact that the math—more workers, higher-earning men, and less family drama—tends to favor parents who manage to get and stay married.

Research by Wilcox, Robert Lerman, and Joseph Price has shown that “higher levels of married-parent families in states are strongly associated with more economic growth, more economic mobility, less child poverty, and higher median family income.” Furthermore, their study found that family structure is “generally a stronger predictor of economic mobility, child poverty, and median family income…than are the educational, racial, and age compositions of the states.”

The ultimate goal of our anti-poverty efforts should go beyond simply “lifting children out of poverty” to helping them stay out of poverty when they become adults.

Marriage is just as important as better job opportunities to curbing child poverty, and it should be part of any serious anti-poverty campaign. But making marriage part of our efforts to combat poverty doesn’t mean pushing marriage on single parents. It means pursuing public policies that make marriage more feasible for lower income Americans and educating future generations about the economic and social benefits of delaying parenthood until marriage.

This includes working to reduce or eliminate marriage penalties in means-tested programs that might be keeping some lower income couples from getting married. At the same time, we should promote marriage as equal to education and work in helping to lift and keep individuals out of poverty. One way to do this is by encouraging young people to pursue what Brookings Institution scholars Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill have dubbed the “success sequence:” education, work, marriage, and parenthood—and in that order. Perhaps this message could become part of our targeted outreach to families in poverty.

The ultimate goal of our anti-poverty efforts should go beyond simply “lifting children out of poverty” to helping them stay out of poverty when they become adults. Because children born to unmarried parents are significantly more likely to experience poverty, promoting marriage over cohabitation and single parenting as best for families should be a fundamental part of any campaign to reduce child poverty.

1. See “Table 4. Poverty Status of Families, by Type of Family, Presence of Related Children, Race and Hispanic Origin, 1959 to 2015,” U.S. Census Bureau, Income and Poverty in the United States, 2015.

2. See pages 14 and 15 of the full Census Bureau report, Income and Poverty in the United States, 2015.