Highlights

Hillary Clinton recently announced an ambitious child care plan—one that some argue promises a host of benefits, including reduced child care costs, more women in the workforce, and most importantly, giving all children the potential for a “healthy start” to life. New York Times columnist Paul Krugman opined, in praise of her plan, that public funding for child care and early education represents an investment in “tomorrow’s workers and taxpayers” and would “make a huge difference to [young children’s] lives.”

There’s little question that government-funded, universal day care would decrease child care costs for parents and increase women’s work hours. But can it really promise a “healthy start” for all children? Numerous research findings suggest we should act with caution precisely because children’s early development matters so much.

The best research on child care was carried out by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development beginning in the early 1990s. The NICHD set out to do its own large-scale, in-depth study after decades of analysis utilizing inconsistent methods came to mixed conclusions on the effects of day care on children’s development. Their study, which has followed the same 1,364 children every year from birth, provides the most comprehensive picture we have about day care in the lives of American children.

Findings from this study indicate that children in the day care of highest quality may experience some cognitive gains even into adolescence. But these small gains have to be weighed against the risks of extensive hours in day care. Even after controlling for day care quality, socioeconomic background and parenting quality, extensive hours in day care early in life predicted negative behavioral outcomes throughout childhood and into adolescence.

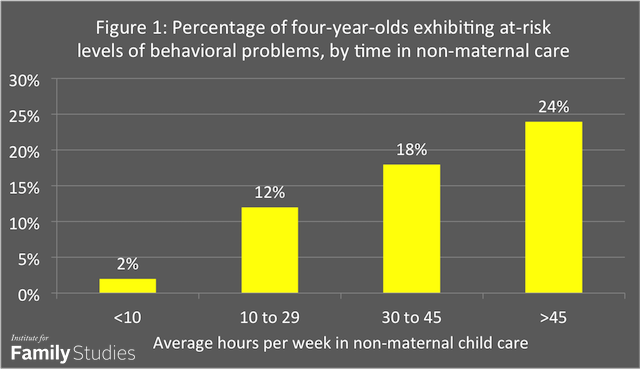

Defenders of day care tend to point out that these negative effects are modest, and that the majority of children who attend day care do not exhibit unusual levels of problematic behavior. For example, by one journalist’s account, in a call with the press about the study, lead NICHD researcher Sarah Friedman “tried to downplay the severity of the [negative] behaviors” linked to child care. However, as I will explain in greater depth below, the effects of day care on some measures of behavior were not insignificant, and rivaled the effects associated with poverty, a subject that draws far more public concern. By age five, 2 percent of children who averaged less than 10 hours/week of child care exhibited at-risk behavioral problems compared to 18 percent who averaged 30 hours or more/week and 24 percent of those in 45 hours or more. (These days, children average 36 hours/week in child care.)

The effects of day care on some measures of behavior rivaled the effects of poverty.

Advocates of universal day care further tend to assume that high-quality day care, at least, can mitigate the challenges children might face because of poverty and difficult family environments, putting them on a trajectory for success in spite of these obstacles. But evidence for that claim is hard to find. True, the NICHD found that moving a child from very poor care at home to very high-quality day care was associated with increased school readiness scores. And attending the highest-quality day care—as measured by sensitive caregivers, high language stimulation, low teacher-child ratios, and extensive teacher training—was associated with improvements in cognitive abilities even 10 years after the children had left child care.

But the cognitive effects were small, and there was an important caveat. Extensive non-maternal care during a child’s first year (more than 30 hours) predicted significantly lower scores on all eight cognitive outcomes included in the NICHD study at age four and a half and in first grade.

Of greater concern, the NICHD study found in repeated evaluations that extensive hours in day care (more than 30 hours/week) during a child’s early years predicted behavioral problems, even into adolescence. By age four and a half, extensive hours in day care predicted negative social outcomes in every area including social competence, externalizing problems, and adult-child conflict, and at a rate three times higher than other children. Where only 2 percent of children who averaged less than 10 hours per week of day care during the first four years of life had caregiver reports of at-risk problem scores, as much as 18 percent of children who averaged more than 30 hours per week did. Family economic status, maternal education, quality of day care, and caregiver closeness did not moderate these effects.

Source: Data drawn from Table 8 of NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2003). “Does Amount of Time Spent in Child Care Predict Socioemotional Adjustment During the Transition to Kindergarten?” Child Development 74(4): 976-1005. Per the study, “Proportions are adjusted for site, child gender, child ethnicity, maternal education, average income-to-needs ratio (6–54 months), 6-month temperament, maternal depression (intercept and slope), parenting (intercept and slope), child care quality (intercept), proportion of center care, proportion of peer group exposure, instability of care.”

Some argue that the problem behaviors observed 9 times more frequently among children with extensive hours of day care still largely fell within the “normal” range for behaviors. Others argue that reports of aggression or disobedience might actually reflect assertiveness in these children. What these arguments fail to appreciate is that as day care hours across the first 54 months increased, so did the likelihood that children would score in the “at-risk” range for behavioral problems. That is, they were close to the threshold meriting clinical intervention. Further, the analyses showed that the externalizing problems reported by caregivers were not merely a reflection of greater assertiveness. Rather, the behaviors specifically reflected aggression (e.g., cruelty to others, destroys own things, gets in many fights, threatens others, hits others), disobedience (e.g., defiant, uncooperative, fails to carry out assigned tasks, temper tantrums, disrupts class discipline) and assertive behaviors (e.g., bragging or boasting, talks too much, demands or wants attention, argues a lot).

The effects of day care did not diminish as children in the NICHD study aged.

As the assessments continued across development, other behavioral challenges emerged. By third grade, children who had experienced more hours of non-maternal care were rated by teachers as having fewer social skills and poorer work habits. Among children who had spent more time in day care center specifically, externalizing behaviors and teacher conflict, too, were elevated. Hours spent in day care centers continued to predict problem behaviors into sixth grade. But by age 15, extensive hours before age four and a half in any type of “nonrelative” care predicted problem behaviors, including risk-taking behaviors such as alcohol, tobacco, and drug use, stealing or harming property, as well as impulsivity in participating in unsafe activities.

The amount of hours spent in day care each week during the first four years of life was the key child care predictor of behavioral problems. In fact, the statistical effect size of the relationship between day care hours and caregiver reports of behavioral problems at age four and a half was so strong that it was comparable to the effect of poverty. Importantly, these statistical effects did not diminish as children aged. The statistical effects linking day care hours with problem behaviors at age four and a half were nearly the same as the statistical effects at age 15. And these links did not differ for children from high socioeconomic backgrounds compared to low socioeconomic backgrounds. Nor did they differ for girls compared to boys, though previous studies had suggested girls would fare better.

To provide some context for comparison, the effect of child-care quantity (30 or more hours/week) on caregiver reported problem behaviors at age four and a half was 152 percent as large as the parenting effect, and 91 percent as large as the poverty effect. In contrast, the positive effect of high child-care quality on cognitive outcomes were 47 percent and 31 percent as large as the effect associated with parenting quality and poverty.

These findings pose important questions for advocates of subsidized day care. The effects of extensive hours in day care endured over a 10-year period of time, at roughly the same size. Such effects, although not enormous, matter in the lives of individual children. And distributed over many children, they have “collective consequences across classrooms, schools, communities, and society at large.”

Quebec’s major expansion of subsidized day care in the late 1990s had the same goals as Hillary Clinton’s proposal: reduce costs to families, increase child care workers’ pay and training, and make child care much more widely available. But carefully done research released last year found increased anxiety, aggression, and hyperactivity as well as worse health, lower life satisfaction, and higher crime rates as children grew into adolescence. Efforts to ease families’ financial burdens and boost women’s work hours should not fail to take such findings into account.

Jenet Erickson is an affiliated scholar of the Wheatley Institution at Brigham Young University. Dr. Erickson holds a doctorate in family social science from the University of Minnesota. Her research has focused on child and maternal wellbeing in the context of work and family, and her in-depth review of the NICHD child care study is featured at FamilyFacts.org.