Highlights

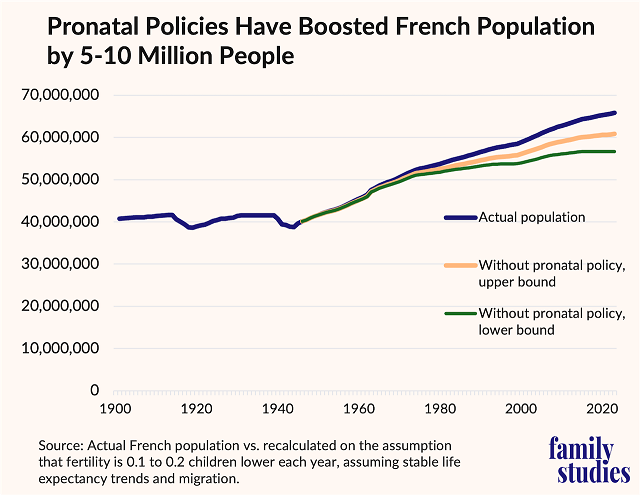

- Without pronatal policies, the French population today would be between 56 and 61 million people: or 5 to 10 million fewer French people. Post This

- The reason France’s population is still growing today rather than staying stagnant or shrinking is because of the pronatal policies of the past. Post This

- If policymakers can find a way to commit to pronatal policy as a long-term project, even “marginal” and “modest” effects can turn out to be—across the generations—massive. Post This

With fertility rates falling around the world, many leaders are looking for solutions. Is there anything that can be done to boost fertility?

For many people, the answer is, basically, no. Read any article about pronatal policy, and it will almost invariably include some comment about the negligible effects of these programs. Even here at the Institute for Family Studies, we have pointed out that the effects are pretty modest, and that cash benefits alone probably can’t get Americans back up to their desired fertility rates.

But the core thrust of this view—that pronatal policy has insignificant effects—is completely and catastrophically wrong: completely wrong, because pronatal policies have massive effects on national population trajectories; and catastrophically wrong, because defeatism about pronatalism can lead to complacency by policymakers and thus even worse outcomes.

France’s wide range of historic pronatal policies (including flexible child care programs, huge tax breaks, direct financial transfers, and benefits in retirement programs) have boosted French fertility by about 0.1-0.2 extra children per woman.

Rather than bore you with yet another literature review showing that pronatal policies tend to boost birth rates, we’ll look at one extensively-studied case: France. Last year, we published an extensive report on fertility in southwestern Europe, which highlighted the relative overperformance of France vs. other similar countries. Prior academic research and our additional findings are decisive: France’s wide range of historic pronatal policies (including flexible child care programs, huge tax breaks, direct financial transfers, and benefits in retirement programs) have boosted French fertility by about 0.1-0.2 extra children per woman, and this effect has been sustained across about 80 years of policy. This margin of effect shows up in detailed studies focused on policy implementation, as well as cross-border discontinuities that emerged only in the period when distinctive French policies were being implemented. France’s pronatal policies caused fertility rates to be 0.1-0.2 children higher than they otherwise would have been.

Now, 0.1-0.2 extra children does not sound like very much. To policymakers, a policy that costs more money and only boosts fertility from, say, 1.6 children per woman to 1.7 children per woman certainly does not sound like “success.” But keep in mind: France’s policies have been durably effective for decades. Generations, even. We can straightforwardly model the overall population effects of these policies. Without its pronatal policies, France’s post-WWII fertility would be about 0.1-0.2 children per woman lower. This means fewer births each year, which would generate changes in subsequent generational sizes and mortality, too. If we make the assumption that migration patterns are unchanged (maybe not a great assumption, but at least a neutral one), it’s easy to calculate what France’s population would have been had it not been for its pronatal policies.

The effects are stark. Today, France has about 66 million residents. Depending on if you think French pronatal policies boosted long-run fertility by 0.1 or 0.2 children per woman, without such policies, France's population today would be between 56 and 61 million people: or 5 to 10 million fewer French people. Under the lower-bound scenario, French population growth would essentially have stagnated after 2010, and the decline would be imminent.

In other words, the reason France’s population is still growing today rather than staying stagnant or shrinking is because of the pronatal policies of the past.

Now, some readers might think my “assume the same migration pattern” assumption is unreasonable. Lower population growth could drive higher migration (if migrant workers are needed to fill spaces counterfactually taken by French-born workers), or lower migration (if smaller population drives lower demand). But neither of these is actually a great scenario. If higher migration caused France to avoid lower population, then the result would be a much higher foreign-born share of French population. If France had offset the entire relative birth loss with migration, the foreign-born share of France’s population would be 15-23%, instead of its actual current value of 10 percent. This would probably have some pretty dramatic effects on French political and civic life, especially since surges in working-class migration cause increases in right-wing voting. If, on the other hand, lower births drove lower migration due to weaker demand, then the true population trajectory would be even lower.

Thus, provided policymakers can find a way to commit to pronatal policy as a long-term project, even “marginal” and “modest” effects can turn out to be—across the generations—massive effects. A mere 0.1 extra children born per woman starting in the 1940s means 5 million extra French people today. Note that in the U.N.’s future forecasts for France, they find that a 0.5 child increase/decrease in fertility predicts approximately 25 million more/fewer French people in 2100, about 80 years from now—essentially the exact same ratio of fertility-changes-to-population-growth over an 80-year period as I suggest France experienced over the last eight decades. For a country of France’s size, 0.1 higher fertility across three generations means about 5 million more people. For the U.S. over 80 years, an extra 0.1 in fertility rates would imply 20-30 million more Americans.

Building a long term pronatal policy means finding policies that won’t be so controversial that the next party in power will repeal them. We’ve identified five policies we think a Republican Congress could consider in 2025, which we think Democrats would probably not actively try to repeal the next time they’re in power. Long-term American pronatalism can begin now.

Lyman Stone is Senior Fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.