Highlights

- The prediction that the relationship stability of marriage and cohabitation will be more similar as family forms become more diverse does not have supporting evidence in the life experiences of children. Post This

- Study: "Differences in the stability and characteristics of married and cohabiting families persist even in contexts where cohabitation is a common part of family life.” Post This

Where did the notion originate that cohabitation and marriage would become more similar as cohabitation became commonplace? Largely from work assessing adult outcomes: the stability of marriages starting with cohabitation compared to “direct marriages,” happiness and life satisfaction among cohabiting and married couples, and domestic violence. For all of these adult outcomes, the “cohabitation gap” or the “marriage premium” shrinks when cohabitation ceases to be an atypical part of the adult life course and approaches becoming a majority phenomenon.

In contrast, Kelly Musick and Katherine Michelmore’s recent work, which was published in the journal, Demography, did not find that outcomes converged in countries where cohabitation was more normative. Why not? A key reason is that they assessed the impact of cohabitation on children’s family stability rather than on adult family stability.

On the surface, it doesn’t seem like focusing on children instead of adults should make that big of a difference. After all, if the cohabitation gap for adult stability closes, then shouldn’t children born into a cohabitating union benefit? Not necessarily. Scholars have obtained “pure” comparisons of adult outcomes according to the legal status of partnerships by observing couples only in their first unions: all adults can potentially be observed once. In contrast, children do not have the luxury of choosing to be born to only their parents’ first unions. We leave out the life experiences of many children unless we also include those born later.

Musick and Michelmore correctly “start the clock” for children’s family stability when the couple has a first birth together—not necessarily the mother or the father’s first birth. This opens the door for parents’ prior union experiences to impact children’s stability.

And it turns out that prior childbirth matters—a lot. In fact, one of the reasons why unions in the United States were less stable than in the seven European countries they also analyzed was that prior children are far more common here: 37% of all first births to a given union were preceded by a child from another partnership in the United States, while the range across the other countries was from 3 to 29 percent.

It is worth noting that prior childbirth mattered even more than education for cross-country differences. The authors provided simulations of what other country’s dissolution rates would look like if they had the same educational distribution, age at first birth, and rates of prior childbirth as the United States. Union dissolution rates would be 43-130% higher than prevailing ones across the seven European countries, with a large share of the difference in most countries coming from prior childbearing.

This is remarkable because when scholars talk about “diverging destinies” they are referring to the way that union instability can compound existing disadvantage, i.e., that the outcomes for children of less-educated parents don’t just reflect lower parental earning power but diverge still further from children of more educated parents because cohabiting unions are more common among the less educated and less stable than marriages. Alternately stated, an existing socioeconomic gap grows because advantaged children additionally benefit from a marital stability premium. Existing work had shown that destinies diverge more because of union patterns in the United States than elsewhere. Musick and Michelmore help us understand this finding more when they show that many children start out with half-siblings who can strain resources and relationships, whether or not they live in the household. Thus, prior instability can beget current instability.

Diverging destinies form one of several strands of research suggesting that despite increases in cohabitation, marital and cohabiting families may retain distinct experiences. Musick and Michelmore pit this perspective against one that predicts the distinctions between cohabitation and marriage will fade. They do not find a clear pattern of evidence that would support the convergence of children’s outcomes: “Our findings complicate…the notion that differences between marriage and cohabitation should diminish as cohabitation becomes more established.”

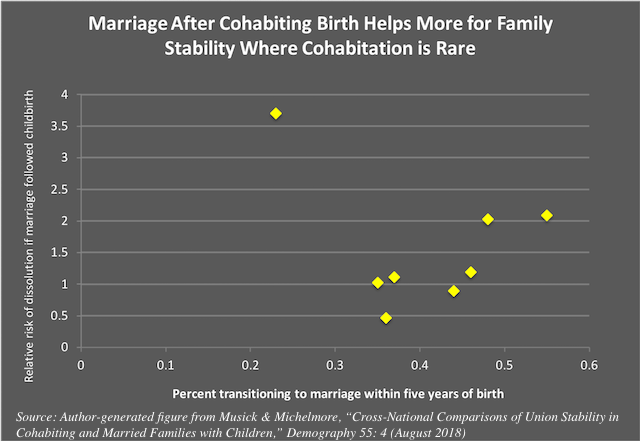

I believe their work does more to challenge that notion than what they describe. They emphasize that children whose cohabiting parents married after their birth rarely experienced the same stability disadvantage as those whose parents never married. However, a simple scatterplot generated from their data indicates that family stability is most similar in cases of pre-birth and post-birth marriage when a low proportion of cohabiting births are followed by marriage (the outlier is Spain).

The implication is that where more cohabiting births are followed by continued cohabitation, the majority of children experience the significant family stability disadvantage associated with cohabitation, and where more cohabiting births are followed by marriage, post-birth marriage doesn’t help to close the cohabitation gap as much. Thus, children born in cohabitation have a persistent disadvantage in either circumstance.

The prediction that the relationship stability of marriage and cohabitation will be more similar as family forms become more diverse does not have supporting evidence in the life experiences of children. I fully endorse Musick and Michelmore’s conclusion that, “Differences in the stability and characteristics of married and cohabiting families persist even in contexts where cohabitation is a common part of family life.”

Laurie DeRose is a Research Assistant Professor at the Maryland Population Research Center at the University of Maryland at College Park and a senior fellow with the Institute for Family Studies. She is also Director of Research for the World Family Map project.