Highlights

- For the first time [in my career as a family doctor], I am seeing a political dimension to parenting. Post This

- Recent studies have called attention to the intersection of politics and depression among adolescents: namely, that left-of-center adolescents are increasingly more likely to be depressed than right-of-center adolescents. Post This

- Today, when I counsel permissive parents on the importance of setting rules and enforcing them, while communicating love for the child, left-of-center parents are more likely to push back. Post This

A mom brought her six-year-old daughter into the office with a fever and a sore throat. I asked the little girl to open her mouth and say “Ah.” She shook her head and clenched her mouth shut. “Mom, it looks like I’m going to need your help here," I said. "Could you please ask your daughter to open her mouth and say ‘Ah’?” Mom arched her eyebrows and replied, “Her body, her choice.”

Wow. This mom was invoking the “My body, my choice” slogan of abortion-rights activists to defend her 6-year-old daughter's refusal to let me, the doctor, look at her daughter’s throat.

I have been a family doctor for nearly 34 years. Until recently, I saw no connection between politics and parenting. Left-of-center parents were no better and no worse parents, on average, than right-of-center parents. Some left-of-center parents were Too Harsh, some were Too Soft, and some were Just Right; and the same was true of right-of-center parents.

Eight years ago, I wrote a book called The Collapse of Parenting, which became a New York Times bestseller. I wrote the book because I had noticed that more and more parents were becoming too permissive. As I showed in the book, that trend toward permissiveness wasn’t confined to families in my practice: scholars now find that the culture of the United States is increasingly a culture in which “children rule.”

Parenting researchers have consistently found that the best parents—the parents whose kids are most likely to thrive as adults—are parents who are authoritative, meaning parents who are both strict and loving. They are not Too Hard or Too Soft; they are Just Right. But in the eight years since I wrote the book, I’ve noticed something new. For the first time, I am seeing a political dimension to parenting. It is now much less common to find left-of-center parents who are both strict and loving. Loving, yes, but not strict. I’m seeing a growing number of parents like the mom I just described—parents who truly believe that it's virtuous to let the kid be in charge, even when the kid is a six 6-year-old with a fever who is refusing to let the doctor look at her throat.

Every day that I am in the office, I now encounter parents who believe in “gentle parenting,” or its close relatives, mindful parenting or intentional parenting. The gentle parent lets the child decide. The gentle parent never uses punishments of any kind, not even time-outs. The gentle parent does not toilet train the child, but instead “models” toileting for the toddler, which will (it is hoped) inspire the toddler to want to use the toilet instead of the diaper. One mother was playing with her son, then gently let him know that she needed to take a break from playing with him in order to do some housework. Her son exploded in anger, hitting and kicking his mom. That mom reached out to Robin Einzig, a leading guru of gentle parenting, to ask what she should do in that situation. Einzig responded without hesitation, “He’s telling you very clearly that right now he needs your presence.” In other words, forget the housecleaning; you have to play with the boy until he decides to stop. Jessica Winter, writing for The New Yorker, observes that gentle parenting requires the parent to transform himself/herself into a “a self-renouncing, perpetually present humanoid who has nothing but time and who is programmed for nothing but calm.” Winter predicts that the next generation can “anticipate blaming their high rates of depression and anxiety on the over validation and under correction native to gentle parenting.”

As a family doctor, I simply did not encounter this kind of parenting 10 years ago. Now I see it every day. And the parents who are practicing gentle parenting are (in my experience) almost always politically left-of-center.

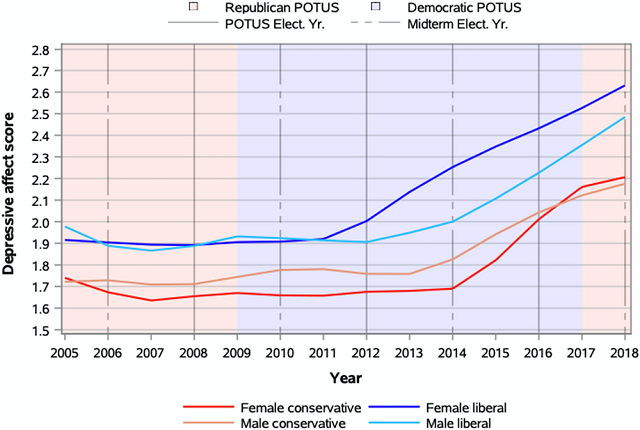

This change may help to explain some new findings regarding political views and depression in teenagers. Researchers have known for decades that teenage girls are more likely than teenage boys to be depressed. But some recent studies have called attention to the intersection of politics and depression among adolescents: namely, the finding that left-of-center adolescents are increasingly more likely to be depressed than right-of-center adolescents. This finding is so pronounced that left-of-center boys are now more likely to be depressed than right-of-center girls. See, for example, this graph by Catherine Gimbrone and colleagues at Columbia University, from their study published last year:

Gimbrone and colleagues try to explain this finding in political terms, arguing that the country veered steadily and increasingly rightward beginning in 2012. Michelle Goldberg, writing for the New York Times, dismissed Gimbrone’s political analysis as simply not accurate. Goldberg suggests, instead, that left-of-center kids are more likely to be on social media than right-of-center kids. She draws on a growing body of research showing that teens who spend more time on social media are more likely to be depressed compared with teens who spend less time on social media. According to Goldberg, left-of-center teens are now more likely to be depressed than conservative teens because left-of-center teens spend more time on social media.

NYU professor Jonathan Haidt recently posted an essay in which he rejected both Gimbrone’s conjecture of a steady rightward shift and Goldberg’s attribution of blame to social media. Haidt argues that the real reason that left-of-center kids are more likely to be depressed compared with right-of-center kids is that left-of-center kids have been taught to catastrophize events, to assume the worst, while right-of-center kids are taught to be more optimistic.

I think both Goldberg and Haidt make good points and their arguments are not mutually exclusive. But they are both missing an explanation which, from my perspective as a family doctor, is more obvious. As I mentioned, I am now encountering more and more parents like the mom I described in the opening paragraph, parents who might best be described as aggressively permissive. They believe it’s actually virtuous to let kids decide everything. And those parents are not randomly distributed along the political spectrum: they are, as I said, overwhelmingly more likely to be left-of-center. Conservative parents, especially conservative church-going parents, still insist that their kids open their mouths and say “Ah” when they bring their kids to the doctor with a fever and a sore throat.

This is a big change. As recently as 10 years ago, it wasn't unusual to find left-of-center parents who were authoritative, even strict. That is less common today. In my experience, permissive parenting is now more common among left-of-center parents than among right-of-center parents. That’s important, because researchers have found that permissive parenting leads to young adults with “less sense of meaning and purpose in life, less autonomy and mastery of the world around them.” Other researchers have found that permissive parenting leads to lower emotional intelligence and lower personal growth. Still other researchers report that permissive parenting is associated with an increased risk of drug and alcohol abuse, and lower academic achievement, while authoritative parenting is associated with lower risk of drug and alcohol abuse and higher academic achievement. The children of permissive parents are more likely to become anxious and depressed. Two decades ago, Brad Wilcox showed that conservative religious parents were most likely to be authoritative—both strict and loving. From my perspective, that’s even more true today.

Today, when I counsel permissive parents on the importance of being more authoritative—setting rules and enforcing those rules, while communicating love for the child—left-of-center parents are more likely to push back. They tell me that they don’t want to be “controlling” or “coercive.” A decade ago, I could have persuaded such parents that kids need structure, rules, and consistency. Today, I don’t have much luck with permissive left-of-center parents: “Her body, her choice.”

I am a family doctor, not a politician. I am not suggesting that left-of-center parents should adopt right-of-center politics. I just ask that parents keep politics out of their parenting. Your child, your teenager, needs you, as the parent, to provide structure, to set boundaries, and to lay down guardrails that are enforced. This has nothing to do with Blue states vs. Red states or Democrat vs. Republican. This is about what every kid needs to thrive.

Leonard Sax MD PhD is a practicing family physician, a PhD psychologist, and the author of four books for parents, including The Collapse of Parenting. More information is online at www.leonardsax.com.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.