Highlights

- When it comes to student achievement and adjustment, the advantage of being raised by married birth parents has actually increased over the last quarter century. Post This

- Students raised in unmarried and disrupted families are more likely to have their parents contacted by schools for conduct or grade issues than those raised by their married birth parents. Post This

- Despite the ballooning number of students getting stellar grades, those being raised by their married birth parents are still more likely to get mostly A's than those in other family forms. Post This

The last quarter century has seen a dramatic increase in grade inflation on student report cards in elementary, middle, and high schools throughout the United States. So much so, that a student’s grade point average (GPA), which was once as useful as an SAT or ACT score, has become almost worthless as a predictor of how well the student would do in college or graduate school. So many students get “A’s” on their report cards now that a straight-A average is hardly a mark of academic distinction anymore. And high school graduation rates continue climbing, even as the 12th-Grade results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) have remained stagnant or even declined. There has also been a notable decline in disciplinary actions by schools for student misconduct or lack of application.

These grading and disciplinary changes are partly the result of well-intentioned, though largely cosmetic efforts to improve social mobility and reduce gaps between racial, ethnic, and economic groups in this country. Even as progressive education reformers have sought to make family background less of a determinant of student success in the classroom, a new IFS research brief highlights evidence from two nationwide household surveys of parents conducted nearly a quarter of a century apart that demonstrate that family factors are as important as ever—or even more so.

The Majority of Students Now Get A Grades

In the 1996 National Household Education Survey, the parents of 40% of all students in elementary, middle, and secondary schools in the U.S. reported that their offspring got “mostly A” grades on their report cards. Twenty-three years later, in the 2019 National Household Education Survey, a 54% majority of students got mostly A grades. The proportion who received D or lower grades fell. As students move from primary to middle to secondary school, they are less and less likely to get “A” grades. But at every level, they are more likely to do so now than in the past.

Students From Intact Families Still Do Better in School

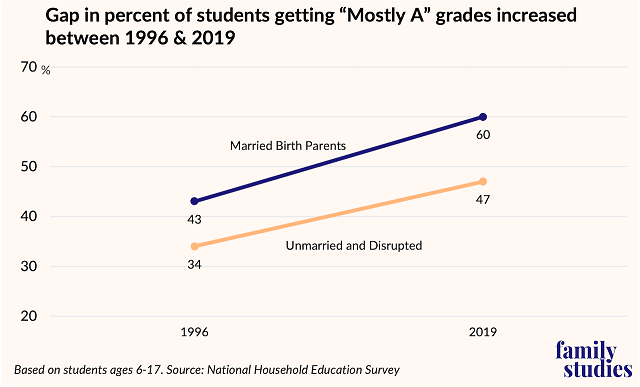

Despite the ballooning number of students getting stellar grades on their report cards, those being raised by their married birth parents are still more likely to get mostly A grades than those being raised by single parents, stepparents, cohabiting birth parents, or other relative or non-relative guardians. This is so even after taking account of parent-education and family-income differences across family types, as well as differences in their racial and ethnic composition.

The figure below shows the adjusted proportion of students from intact families who got mostly A’s in 1996 and 2019, and the comparable proportions for students from unmarried and disrupted families.

The intact family advantage has increased as grading has become more lenient. It went from 1.45 times better odds in 1996 to 1.68 times better odds in 2019, a statistically significant change. The odds ratios are adjusted for socioeconomic and demographic differences across family groups in parent education and family income levels, and sex age, and racial and ethnic composition of the groups at each timepoint.

Fewer Parents Are Being Contacted by School for Student Problems

In 1996, 27% of parents reported being contacted by their child’s school because of schoolwork problems. In 2019, that number had fallen to 22%. In 1996, 22% were contacted because of the child’s conduct in class. By 2019, that number had fallen to 17%. In addition, the proportion of students who repeated a grade fell from 13% in 1996 to 6% in 2019.

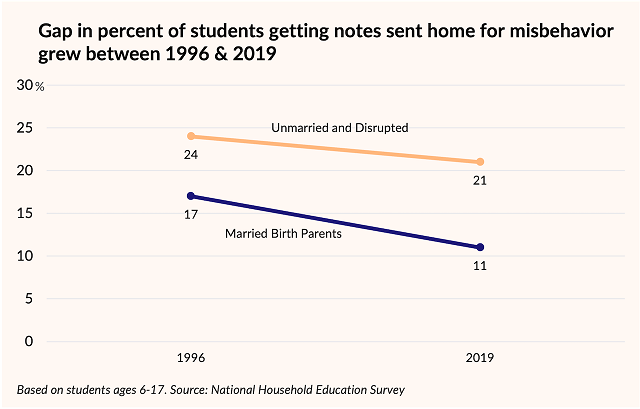

But Unmarried or Divorced Parents Still Get Contacted by Schools More

Despite the overall drop in school contacts with parents, students being raised in unmarried and disrupted families are more likely to get notes sent home from school for not doing homework or conduct problems than those being raised by their married birth parents. This is so even after taking account of parent-education and family-income differences across family types, as well as differences in their racial and ethnic composition, as the figure below shows. The disrupted family disadvantage increased, even though disciplinary practices have become more lenient—from 1.63 times higher odds in 1996 to 2.09 times higher odds in 2019.

Understanding the Trend Evidence

A comparison of national surveys conducted in 1996 and 2019 provides striking evidence of more lenient grading and permissive disciplining of students in elementary, middle, and high schools in the U.S. Despite these trends in school practices, the advantage for student achievement and adjustment of being raised by married birth parents has actually gotten greater over the last quarter century. There are also continuing but not larger gaps in student achievement and behavior associated with parent education and family income disparities, as well as with the sex and race and ethnicity of the child.

A possible explanation for the increased importance of marriage and marital stability for student success is that married parents comprise a more select, motivated, and advantaged group than 23 years ago, whereas the mix of formerly married and never-married adults who make up the unmarried group of parents has changed in ways that put children at still greater disadvantage. Both marriage rates and divorce rates have gone down, along with a decline in teen births. But unmarried birth rates have not declined. That means that children of single mothers are now more apt to have a never-married rather than a divorced mother.

This matters because while children of divorced mothers often experience the stresses of parental conflict and separation, they are more likely than children of never-married mothers to have college-educated mothers and benefit from parental custody, visitation, and child support agreements. They also tend to see more of their non-custodial parent (usually the father) and gain from his attention, care, and financial assistance. They are also more likely to have mothers who are gainfully employed.

At the same time, today’s married mothers and fathers are older, having started parenthood at older ages, more apt to both have college degrees, and more likely to both be in the paid labor force than was the case in the mid-1990’s. They are more likely to have followed the “success sequence” of first, finishing school, then finding employment, then getting married, and only then, having children. Never-married mothers have, by definition, not followed that sequence.

Dealing with Family-related Disparities

The results reported here are a further demonstration of the difficulty of overcoming family influences—both hereditary and environmental—on student achievement and adjustment. Ascribing that difficulty to inferior teaching or insufficient allocation of resources ignores the enormous amounts of money and effort that have been devoted by local, state, and federal governments to addressing achievement gaps over the past 60 years. It is well past time for educational policymakers to reconsider the influence of family structure on student success and what goals and methods might be achievable for helping more students truly succeed.

To read the full research brief, including notes and additional figures, go here.