Highlights

- Property taxes are the least antinatal kind of tax. Post This

- Property tax carveouts overwhelmingly tax young families to subsidize everyone else. Post This

- There’s basically no difference in fertility rate across levels of sales and income taxes. But there is a huge difference in property taxes. Post This

Around the country, property taxes are one of the main ways that local governments finance things like police, schools, local roads, fire departments, and other services. As we laid out in a recent report, these kinds of basic government services are hugely important for families. More than almost anything else, Blue States’ failures to provide the kind of basic services that most families want is a key reason families are migrating away to Red states.

Property taxes are often unpopular. Especially for older people on fixed incomes, there is strong political pressure to cut property taxes. But this is a mistake. While no taxes are good for families, property taxes are, objectively, the least bad form of taxation. This post will lay out some evidence for why property taxes are not a terrible way to finance local government, and why state and local governments should avoid providing any kind of special carveouts reducing property taxes. Because these carveouts usually subsidize small apartments that most families don’t want, large landholdings, or older people who don’t have young children, property tax carveouts overwhelmingly tax young families to subsidize everyone else.

Fertility Gaps are Smaller When Property Taxes Are High

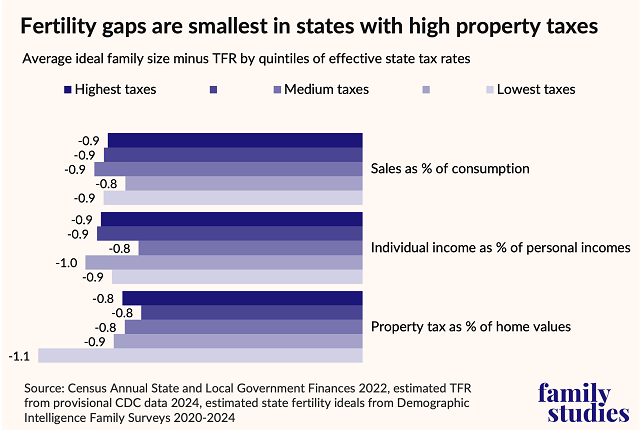

To start with, it helps to think about the basic geography of taxes. Here, I will compare sales taxes as a percent of household consumption, income taxes as a percent of household income, and average property taxes paid as a percent of owner-occupied real estate values to state-level total fertility rates. For simplicity, I group states in five categories: the 10 states with the highest tax rates in 2022 (the latest complete data) in each category, then the next 10, and so on.

Now, it is also helpful to focus not just on the number of children people have, but on fertility preferences too. The IFS Pronatalism Initiative is committed to advancing policies that help people close the gap between their fertility preferences and their fertility outcomes. So I’ll use state-level data on fertility preferences from surveys conducted from 2020 to 2024. Then, I’ll take the gap between that number and total fertility rates in 2024.

In essence, this article will ask what kinds of tax rates are most associated with families having fewer kids than they would like to have? Or, to put it another way, what taxes are most clearly obstacles to family formation?

As the figure illustrates, there’s basically no difference in fertility rate across levels of sales and income taxes. States with high and low taxes in those areas have pretty similar fertility gaps.

But there is a huge difference in property taxes. The largest fertility gaps are in states with very low property taxes. The smallest fertility gaps are in states with relatively high property taxes.

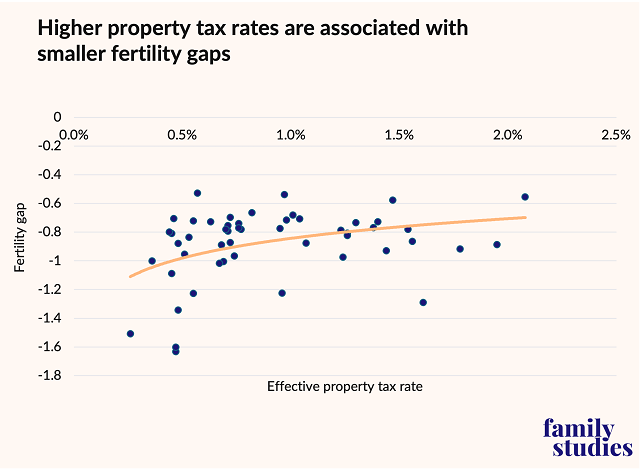

Here’s the property tax vs. fertility gap data in more detail:

The effects are obviously a bit noisy, but the key intuition is that it really is the case that states with very low property taxes as a share of home values are states where families wish they could have more kids but are actually struggling to hit those goals, such as: Hawaii (0.3% effective property tax rate, -1.5 child fertility gap); Idaho (0.5% effective property tax rate, -1.6 child fertility gap); Utah (0.5% effective property tax rate, -1.6 child fertility gap); or Delaware (-0.5% effective property tax rate, -1.3 child fertility gap). Idaho and Utah may not seem like the classic example of states where families are struggling, but, in fact, the ratio of home prices to young adult incomes in Salt Lake City, for example, is among the highest in the nation. A median house in Salt Lake City costs more than 12 times the median income of 20-34 year olds, according to the latest complete data (the 2018-2022 American Community Survey).

High Property Taxes Don’t Always Mean High Housing Costs

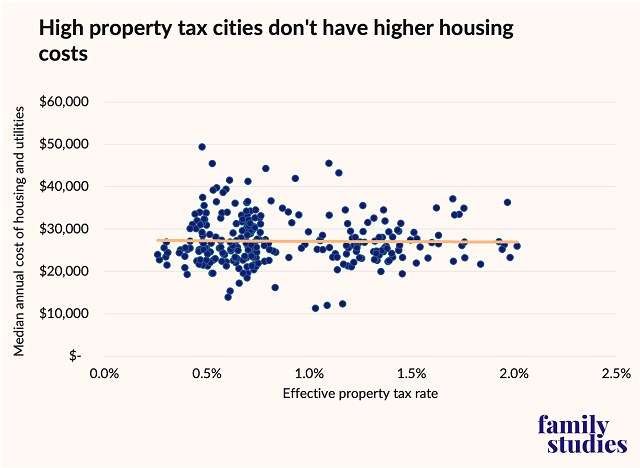

The results above probably seem counterintuitive. Property taxes are a significant part of the cost of housing, and housing is a core part of the cost of having kids, and we know from high-quality studies that lower housing costs boost fertility. If low housing costs boost fertility, why don’t lower property taxes boost fertility?

There are several answers.

- First, housing is complicated: property taxes have different effects. Higher property taxes obviously increase the cost of housing. They do this for both homeowners (directly) and non-homeowners because landlords pass on some of the tax cost to renters. That’s bad for fertility.

- However, property taxes also reduce home prices. Because property taxes are part of the permanent cost of homeownership, higher property taxes get partly incorporated into home prices. Tax hikes lead to lower prices.

- Third, local governments with low property taxes don’t necessarily have lower taxes overall. They just charge more taxes in other ways, or they may provide poor-quality public services. Nobody likes paying property taxes, but property taxes are better than local income taxes or local sales tax, or being nickel-and-dimed every time you interact with the government, or the local police department using speeding tickets as a revenue source instead of a safety priority.

- Fourth, property taxes create much smaller economic distortions than other kinds of taxes and encourage efficient markets for land and housing.

To begin with, here’s the correlation between average all-in housing costs including mortgage, rent, property insurance, taxes, and all utilities vs. property tax rates. Because property taxes influence home prices, construction, and carrying cost for institutional buyers, and even the quality of local public services, to understand the actual relationship between home costs and property taxes, we have to check how these taxes relate to all the costs of owning a home.

There is no correlation between property taxes and overall home costs: tax cuts cause price hikes. When localities cut property taxes, houses simply get more expensive. These effects tend to be concentrated in areas where regulations on new houses are most intense; in America, that means cities and old, tree-covered suburbs. Prices also go up the most for any category of property exempted from property taxes. If big homes have lower taxes, prices of big homes will go up; if single-family homes have lower taxes, prices of single-family homes will increase. Studies finding low rates of “capitalization” of property rates are often failing to account for unusual exemption patterns, or are based on misreported tax data. Thus, it’s totally possible to say that property taxes are the least antinatal kind of tax, and also that high housing costs are a big problem for families.

Young Families Need Jobs, and Property Taxes Can Help

Finally, the argument in favor of property taxes vs. other kinds of taxes ultimately rests on the broader economic effects of various taxes. Decades of economic research show that property taxes are by far the type of tax that does the least damage to economic and job growth. The reason for this is simple. When you tax something, you get less of it, but there’s a lot of variety in how much less of it you get. So, for example, if you tax name-brand Pop Tarts but not similar generics, you wouldn’t raise much revenue at all, because most people would just switch to the generics. On the other hand, if you taxed everybody a fixed amount with no change, that tax wouldn’t really affect behavior. There’s no way to avoid it besides dying.

Property taxes are the least antinatal kind of tax.

Income taxes punish work and investment, which is a problem because work and investment are the basis of virtually all economic growth. Thus, personal and corporate income taxes are by far the worst kind of tax because they directly tax the source of economic growth that generates the prosperity families depend on to support themselves. Sales taxes are better but also have negative growth effects: by taxing consumption, they often accidentally tax business inputs, and beyond that, they discourage consumption. People who don’t feel like they’re doing well economically don’t start families, and so long run growth suffers.

Property taxes, on the other hand, tax a variety of different things: land, buildings, cars, sometimes other property that tend to be relatively insensitive to tax rates. Not entirely, of course, but experimental evidence shows that home construction actually doesn’t respond very much to property tax rates. And in fact, most of the variation in house prices around the country is explained by variation in underlying land prices, rather than physical structures, and as a result most variation in property taxation comes from the land itself, not the house on it.1

The very reason people hate property taxes is the very reason property taxes are good: they are incredibly hard to avoid. Renters pay them via their rents, homeowners pay them directly, and even tourists pay them since any kind of land cost will be capitalized into hotel rates and local price levels.

Property Tax Exemptions Usually Harm Families

Property taxes are notoriously complicated, with a wide range of exemptions and special conditions. The most common such programs are deductions from assessed value for disabled people, senior citizens, veterans, and sometimes low-income people. Other common carveouts include policies freezing assessed values at their most recent sale price. Farmland also often has certain exemptions or reduced rates. Moreover, big developers building apartment buildings can also often get property tax breaks.

On the other hand, I was not able to find evidence of a jurisdiction anywhere in America that provides property tax deductions for having children: not one. At the same time, states like California openly discriminate against families by locking in property tax valuations based on the most recent sale: wealthy retirees can pay trivially small tax burdens on multimillion-dollar homes, while their children are forced to raise their grandchildren in a miniscule apartment.

When states “protect” retirees with generous exemptions, they are essentially raising taxes on young people. It ends up hurting retirees, too. An older woman I know owns a home worth over $1 million. Her kids live many hours away. She’d like to sell and move to a modest home near her grandchildren. But her assessed valuation is about $350,000—and under $3,000 a year in property taxes. A home near her grandchildren with enough space for them to visit will cost $500,000, and about $5,500 a year in property taxes. In other words, even though she would be downsizing, her annual tax bill would grow. Bad property tax policies are paying this grandma to live far away from her grandkids. At the same time, across all of society, as older Americans receive subsidies to stay in large homes, young families are forced into apartments that suppress marriage and family formation.

The solutions here are obvious. First, to the extent possible, special carveouts and exemptions should be repealed. Everybody should pay property taxes at the same rate.

To the extent exemptions are offered, states should consider providing subsidies to the families with children who most urgently need space. IFS scholar Brad Wilcox recently proposed as much for Texas. One reasonable suggestion would be that families could be exempted from any change to their property tax assessment in any year in which they have a dependent child at home; or, as Wilcox suggested, a piece of the assessed value could be knocked off per parent in the home; per-child exemptions would also make sense. There is no reason to give senior citizens, whose homes are paid off and whose incomes are subsidized by working parents through Social Security and Medicare, special property tax breaks while expecting parents to foot the entire bill.

The better solution is to make everybody pay the same rates. But if legislators want to offer property tax carveouts, they should focus on encouraging marriage and childbearing.

Lyman Stone is Senior Fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.

1. Note that this is not equivalent to saying that most taxes paid are on land: in practice, assessments on structures are sometimes a large share or almost the entirety of an individual tax bill. However, across the country, most variation in real estate prices is explained by variation in land costs in an area, not variation in actual construction cost of the structures on land.