Highlights

- European data suggest that grown children’s sense of what they owe aging parents can vary dramatically across societies. Post This

- Culture and religious heritage are powerful forces, but economic headwinds in countries where fewer grown children are responsible for more elderly relatives could prove more powerful still. Post This

- The percentage of European adults who agree that "Adult children have the duty to provide long-term care for their parents” varies wildly by country. Post This

Among parenthood’s many changes, new parents frequently seek out more spacious homes in neighborhoods with good schools. But parents might also want to consider the sort of relationship they want to have with their (eventually) grown children. European data suggest that grown children’s sense of what they owe aging parents can vary dramatically across societies.

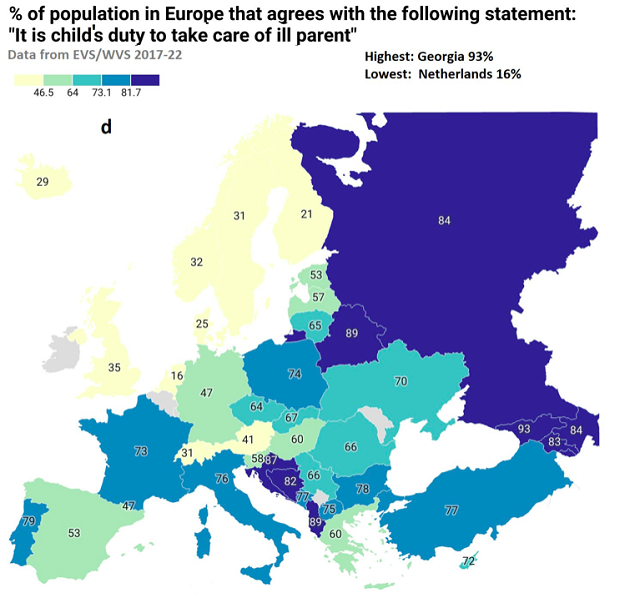

Using data from the most recent waves of the European Values Survey (EVS) and World Values Survey (WVS)—which are conducted every nine and five years respectively—Twitter user @albanianstats created a map illustrating the percentage of each European country’s adults who agreed with the statement "Adult children have the duty to provide long-term care for their parents.” The numbers swing wildly across the continent from Georgia’s high of 93% to the Netherlands’ low of 16 percent.

Source: @albanianstats. Used with permission.

While the Biblical dictate to honor one’s mother and father broadly informs Europe’s cultural heritage, the guide to that belief isn’t strictly linked to most countries’ current religiosity. The way religious ideas about family life manifest also isn’t so predictable in an increasingly post-Christian Europe.

Consider Georgia, the country that tops the list. Pew Research describes 50% of adults in traditionally Orthodox Georgia as “highly religious.” This is fairly high in a contemporary European context, though Georgians rank behind Romania at 55% and Armenia at 51%, in that regard. While nearly all Georgians feel a duty to help aging parents, only 73.7% of Georgians agree or strongly agree that “it is a duty towards society to have children,” placing them behind Bulgarians, 82.7% of whom accept such a responsibility.

In the Netherlands, by contrast, Pew reports that only 18% of adults are “highly religious.” Religious Nones now constitute a majority of the traditionally Protestant and Catholic country. Among Catholics in the Netherlands, only 7% attend Mass at least weekly.

Only 3.1% of the Dutch consider it a societal duty to have children; the only other people who posted single digits for this question are the Danes at 4.1%. Among Dutch adults, 62.9% have tried to inspire pride in their parents.

In between those two extremes is the rest of Europe. While not quite as high as Georgia’s rate, 84% of Russian adults, 79% of Portuguese adults, 76% of Italian adults, 74% of Polish adults, and 73% of French adults feel a filial responsibility to care for aging parents. Germans nearly split the difference with 47% agreeing their parents can count on them.

On the flip side, there are other countries closer to the Netherlands’ range. For example, 35% of adults the United Kingdom, 32% of adults in Norway, 31% of adults in Sweden, 29% of adults in Iceland, 25% of adults in Denmark, and 21% of adults in Finland agree aging parents should rely on them.

These are numbers that should also be fairly stable over time. As Kseniya Kizilova, Head of the World Values Survey Association Secretariat, explained to me via email, surveys can be conducted in several year waves, as opposed to annually because “both WVS and EVS study people's values which don't change that quickly.”

Still, there is clearly variety across Europe’s national borders. So, what explains the divide? In a Twitter exchange with me, @albanianstats, an "assistant researcher for a [US-based] project in demographics/political science," posited, “1) A higher percentage correlates with a higher emphasis on family and traditional values. Countries with the lower values tend to be more individualistic in nature, and children there become independent of the family household earlier in life. 2) It is also related to the performance of healthcare institutions, or at least, to how much people trust those institutions. People in the countries with lower values generally trust the system to do the work.” Finally, the researcher noted, “the countries with the lower percentages tend to be Protestant countries, which may also explain the more individualistic nature of those societies.”

For his part, Professor Christian Smith, the William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Sociology at the University of Notre Dame, told me,

the answer is a complicated mix of (a) historical religious tradition (not attendance), (b) how well developed the welfare state is (thus reducing the need for care from children), and (c) a generally traditionalist, familistic cultural tradition operating somewhat independently of the first two factors. I don't see any single correlations here.

Smith added, “Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Iceland have had the strongest welfare states in Europe, more so than [France, Germany, and Italy].” In other words, parent-child relationships not only depend on the unique individuals involved but are also influenced by different societal and religious forces across Europe.

Looking ahead, it will be interesting to see if these trends persist. Will Europe’s low fertility rates put economic pressure on generous welfare benefits? If those benefits are reduced, will adults in Nordic countries—where fertility is falling—start sounding more like adults in Georgia?

Culture and religious heritage are powerful forces, but economic headwinds in countries where fewer grown children are responsible for more elderly relatives could prove more powerful still. As populations age and shrink, governments will face increasingly difficult choices about public spending. It is entirely possible that many more European adults will care for their aging parents in the years ahead as that becomes the best option for families.

The best way for Europeans to preserve their generous social safety net for the aging would be to multiply, maximizing the number of European young. Without that, the European future is unlikely to look like the European present.

Melissa Langsam Braunstein is an independent writer in metro Washington.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.