Highlights

- Stay-at-home mothers are not miserable, but tend, in general, to find a lot of satisfaction in the work of caring for their families. Post This

- Survey evidence from two large, long-running survey programs shows that stay-at-home mothers are in fact just as happy as other mothers. Post This

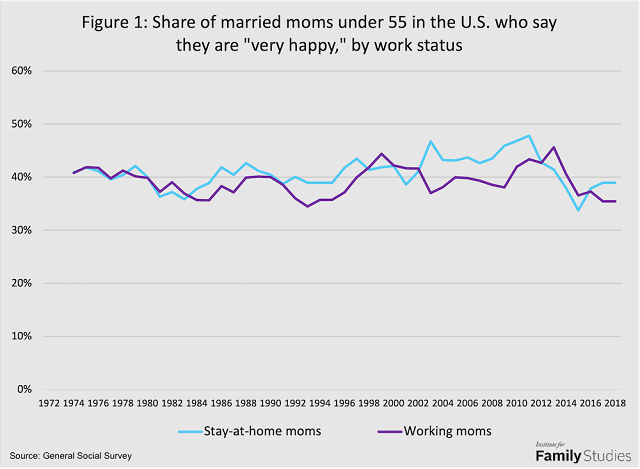

- Stay-at-home moms had about the same likelihood of being “very happy” as working married moms. Post This

Are stay-at-home moms unhappy? As strange as it may sound, the answer to this question has important policy implications. In a recent New York Times piece, liberal policy advocate Matt Bruenig suggested that any child care program should also have an at-home-care allowance provided to ensure that families not using center-based care are not penalized. In response, many progressives, including columnist-turned-Substack writer Jill Filipovic, tarred his proposal as sexist. Filipovic made many arguments about why a home-care benefit is bad (despite such benefits being common in many of the Nordic social welfare states she says the U.S. should emulate), but the most striking claim is this one: the problem with a home-care benefit, she says, is that it encourages women to stay home with their kids, and being stay-at-home mothers makes women miserable. If this claim is true, it would be an important issue to consider. Nobody wants to make moms miserable!

However, it turns out that there is little to no support for Filipovic’s claim. Indeed, there are at least three good reasons why Filipovic’s argument is nonsense: first, home-care benefits, which provide money to stay-at-home parents, might change the happiness outcomes of being a stay-at-home parent; second, the actual academic evidence on this question is not extremely empirically robust, but the evidence that does exist suggests there are little-to-no differences in happiness between stay-at-home and working mothers; third, survey evidence from two large, long-running survey programs shows that stay-at-home mothers are in fact just as happy as other mothers. Although there are no doubt many stay-at-home mothers who are stressed, anxious, worried, tired, or unhappy, there is very little evidence that they differ in this regard from other mothers.

Money Matters

It must be noted before going further that this entire debate hinges on an elementary misunderstanding. Filipovic and others argue that society should not support stay-at-home parenting because it makes parents miserable. Whether or not that claim is true, the policy implication is nonsense: if the people doing the valuable work of raising kids at home are generally miserable (in a time when there are not enough child care spaces to house all kids in America), that’s an argument for providing them with more support, not less.

Moreover, it’s perfectly possible that living in a society where the work of raising children at home is a thankless and generally uncompensated task could very well cause most at-home parents to be unhappy. But there’s no reason to suppose this unhappiness would persist if the workers were paid. Most of us would be unhappy with our jobs if we were not compensated to do them. Since stay-at-home mothers, on average, are in lower-income families and take major career hits to provide care for their children, it’s not unreasonable to believe they might be a little frustrated. But again, this is not a reason to withold an at-home-care benefit; it’s a reason to provide such a benefit. Prior academic research supports this idea, indicating that the happiness effects of parenting vary based on how much policy support is provided to parents.

The Research Disagrees

The question of whether or not stay-at-home mothers are more or less happier than other women has been a topic of considerable academic study. Unfortunately, all of these studies face a similar problem: who chooses to be a stay-at-home mother is not random, and women may have an idea about what their role will be many years before they have children, and thus may adjust their educational, work, and relationship choices in view of that idea. This problem of endogeneity is very hard to solve. Researchers usually solve it by finding “natural experiments,” that is, cases where something more-or-less random happened in the world to change circumstances for one random group of people but not another similar group. Unfortunately, almost every plausible event that might change the odds a woman chooses to be a stay-at-home mom also has other confounding effects. A recession might cause more women to stay at home, but that’s not because they want to be “stay-at-home moms,” but because they are unemployed. Thus, there are no quasi-experimental studies of the effect of stay-at-home status on mothers’ happiness. Filipovic’s claims that stay-at-home mothers are much worse off, then, isn’t really a claim about causality, because there are in fact no extant studies of this topic from which causality could be reasonably inferred.

Families that choose to have one parent stay at home suffer considerable income losses, even though they are doing work that almost everyone recognizes as valuable.

But there are plenty of studies on the correlation between stay-at-home status and happiness. Two studies in particular are important to assess. The first uses a longitudinal survey called the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) and finds that, controlling for characteristics at a young age (i.e., before marriage), women who stayed more attached to the workplace had better physical and mental health around age 40, but mental health was worse for women who had “interrupted” careers, i.e. who left the workforce and then returned. Women who remained out of the workforce did not have significantly worse mental health at age 40. Moreover, even for physical health, there were similar or larger effects of divorce (negative) or having an extra child (positive). These effects are important to consider, since stay-at-home mothers have lower divorce rates and higher fertility rates. Nor are these outcomes coincidental: workplace promotions of younger spouses (usually, but not always, wives) actually cause higher divorce rates. Thus, while being a stay-at-home mother might have some adverse effects on physical and mental health, being highly successful in one’s career might too. In a society where the work done by primary caretakers at home goes largely uncompensated, those caretakers, usually women, face a Catch-22.

The second study of interest uses the General Social Survey, and shows that “satisfaction with work” has changed over time for women. In the 1970s, Filipovic’s characterization of stay-at-home mothers might have been reasonable: stay-at-home mothers in the 1970s really did report lower satisfaction with their work roles (which, in this case, included their work at “keeping house”). But by time of the latest survey wave assessed, 2012, the relationship had flipped: stay-at-home mothers reported slightly higher satisfaction with their work than other mothers.

Stay-at-Home Mothers Are Not Miserable

The academic evidence doesn’t lend much support to the idea that being a stay-at-home mother will make a woman miserable. But to some extent, these sophisticated approaches are unnecessary. If being a stay-at-home mother causes women to be unhappy, then it should be possible to simply compare the happiness to stay-at-home mothers to other parents.

I use two survey datasets to assess this issue: the World Values Survey-European Values Survey integrated data (WVS-EVS) with over 600,000 respondents in 115 coutries, and the General Social Survey (GSS) in the United States. Together, these two surveys provide both a thorough look at stay-at-home mothers in the U.S. across a long-time span, and a cross-cultural assessment of stay-at-home motherhood around the world.

As a first check, I simply looked at the share of married mothers under age 55 in the GSS who said they were very happy, broken out by their work status. Figure 1 shows the results; as you can see, stay-at-home moms had about the same likelihood of being “very happy” as working married moms.

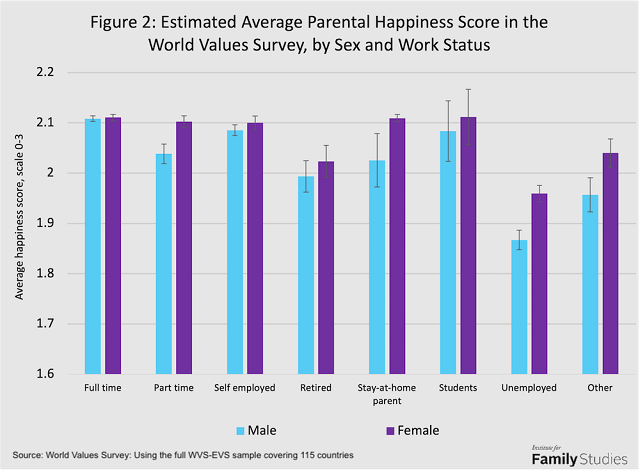

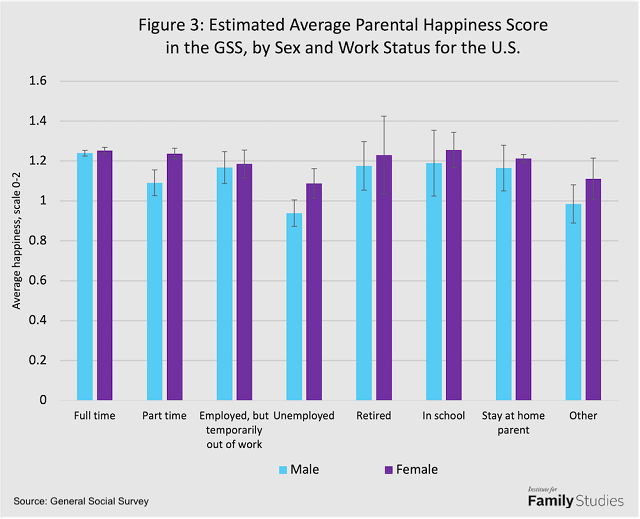

Figure 2 below shows the average predicted happiness (on a scale of 0 to 3) at the mean of control variables, for each sex and work status group in the WVS-EVS data, and Figure 3 shows the same for the GSS, but on a scale from 0 to 2 given the GSS’ different options in its happiness question.1

The categories used in the two datasets are slightly different, but they show broadly similar results. Full-time working mothers and fathers have identical levels of happiness. For men, part-time work is associated with lower happiness, but this isn’t true for women.

For both data sources, unemployment is associated with lower happiness; and in both data sources, unemployment has a more negative association with fathers’ happiness than with mothers. Students tend to be fairly happy, with women perhaps being slightly happier in school. And finally, stay-at-home mothers have virtually identical self-reported happiness as other women. In the WVS-EVS data, stay-at-home fathers have lower happiness, while in the GSS data, stay-at-home fathers are not significantly different from stay-at-home mothers.

Unemployment is associated with unhappiness, but being a stay-at-home parent (especially a stay-at-home mother) is not. While it’s possible there is some negative causal effect occurring that is offset by other factors, it is unlikely to be a large negative effect given how small the observed differences are.

Based on these surveys, stay-at-home mothers do not appear to be miserable. They have virtually the same self-rated happiness as other parents. The idea that entrance into the workforce has some extraordinary happiness-boosting effect on women is therefore a myth.

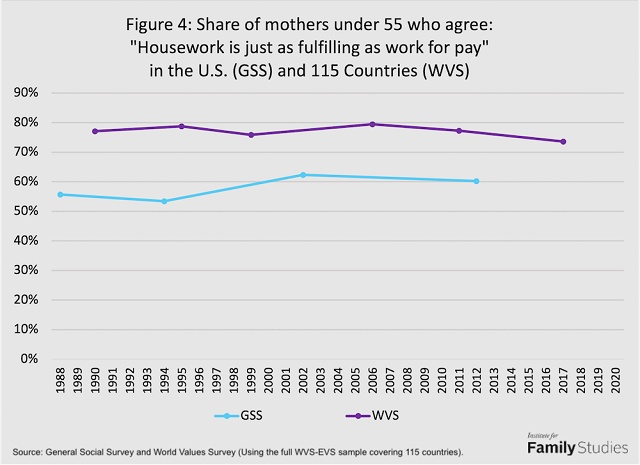

Moreover, it’s a myth based on a calculated refusal to listen to what mothers themselves say. Figure 4 below shows the share of mothers under the age of 55 who agreed with the statement “Being a housewife is just as fulfilling as working for pay.” The WVS-EVS does not provide respondents a “neutral” option, whereas the GSS does, which explains the durable difference between the two over time.

Strong majorities of mothers under 55 agree that housework is as fulfilling as employment. Depending on the year and the survey you prefer to cite, between 53% and 79% of mothers had this view. If being a stay-at-home mother is in fact a miserable lot in life, then these mothers must all be terribly mistaken about what is fulfilling to them, a rather strange position to advocate. It’s much more plausible to just take mothers at their word: some mothers truly do find employment to be more fulfilling that work in the home, but not all, and not even a majority. And this may explain why stay-at-home mothers are not miserable—many of them see the work they are doing as valuable, important, and satisfying.

Rather than smear stay-at-home mothers as miserable women who have failed at their careers as Filipovic does, the real story points to important policy conclusions. Stay-at-home mothers are not miserable, but tend—in general—to find a lot of satisfaction in the work of caring for their families. Very likely many mothers and fathers would prefer to shift their work-life balance a bit more toward family and away from work. Unfortunately, making that shift isn’t always an option because many families face financial constraints and thus both parents have to work. Families that choose to have one parent stay at home suffer considerable income losses, even though they are doing work that almost everyone recognizes as valuable. The logical solution, then, is to provide stay-at-home parents with compensation equivalent to the subsidies provided to parents using center based child care. If the government spends $4,000 per child on child care for enrolled children, then a comparable amount should be provided to stay-at-home parents.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

1. In both datasets, I measure average self-reported happiness levels for mothers and fathers ages 25-54, broken out by their work status. In both datasets I include variables controlling for marital status, age, survey year, and religiosity. In the GSS I also control for race, and in the WVS-EVS I control for the country in which the survey was conducted