Highlights

- Make the expanded CTC permanent, instead of a one-year boost, and make it a monthly, universal child benefit. Post This

- Dare the GOP to make good on its newfound self-conception as a multi-ethnic, working-class party, one whose economic and political interests would be ill-suited by objecting to putting more money in the pockets of working-class parents. Post This

Editor’s Note: With a new administration in the White House and growing interest in legislation to directly aid families, IFS has convened a symposium of scholars to consider the merits of various policy proposals that are being debated on Capitol Hill, including the child tax credit, a child allowance, universal child care, and paid family leave. IFS policy fellow Patrick Brown kicks things off this week with an essay on expanding the Child Tax Credit.

We all have unlucky numbers. Fans of the Atlanta Falcons, for example, will always be haunted by the numbers 28 and 3. The digits that give me nightmares are .94 percent.

During the 2017 debate over the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, only 29 Republicans were willing to set the corporate tax rate at 20.94%, instead of 20%, to allow the Child Tax Credit (CTC) to be refundable against both income and payroll taxes. (Just nine Democrats proved their seriousness by voting for a proposal that would cut child poverty at the risk of giving the opposing party a political win.)

That .94 percent was too precious to risk on poor and working-class families, though apparently not so precious to avoid having the final rate negotiated to 22 percent. Subsequent bargaining increased the refundable portion of the credit (technically, the Additional Child Tax Credit,) by $300. But in turning down the Rubio-Lee plan to allow the CTC to be refunded against income and payroll taxes, Congress continued to keep many low-income families out of a tax provision intended to allay the cost of having children.

At a certain level of abstraction, the CTC reduces tax liability for households by $2,000 per child, but only $1,400 (at most) of that is refundable–that is, it is sent to parents if they do not have sufficient tax liability to wipe out. In a recent working paper, Jacob Goldin and Katherine Michelmore found that roughly “three-quarters of white and Asian children are eligible for the full CTC, compared to only about half of Black and Hispanic children.” Eighty percent of children who do not receive the credit don’t qualify because of insufficient parent earnings, they estimate, and removing that requirement—in effect, creating a universal child benefit, where all children would receive money regardless of parental earnings—would provide a boost to nearly 6 million children, predominately in the lower third of the income distribution.

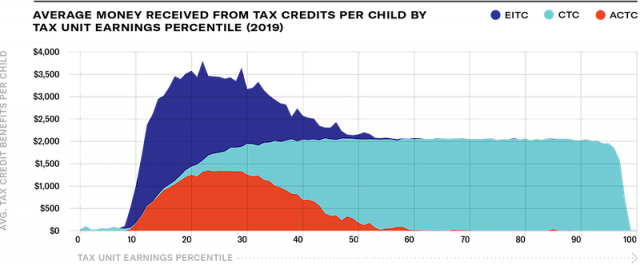

Figure 1 - Credit: Matt Bruenig, People's Policy Project

The unwillingness of Republicans to go to bat for working-class families inspired epic Twitter threads at the time, and only grew more galling as GOP figures touted the CTC expansion as if it were the motivating factor of the 2017 tax package.

The foolishness of getting hung up over that .94% is now coming home to roost. The Rubio-Lee plan was not perfect but would have expanded the CTC to reach more low-income parents. Instead of getting credit for taking a large bite out of child poverty and making it easier for low- and middle-income parents to make ends meet, Republicans are now set to watch the Democrats introduce some form of a universal child benefit, as proposed by the incoming Biden administration.

President Biden’s plan would increase the CTC by 50% to $3,000 per child for one year (at least for now), with an additional $600 per child under age 6. That entire amount would be refundable, so all families would be eligible for the $3,000 payment so long as they filed a tax return.

The CTC expansion should be eligible for Senate reconciliation procedures, meaning the Democrats have enough votes to pass it, barring any defections. But the design and implementation questions of a child benefit is still an open question.

A conceptually sound, if maximalist, position was recently staked out by the People Policy Project’s Matt Bruenig, who proposes scrapping the host of child-related provisions in the tax code for a straight-forward universal benefit. If we were starting from scratch, something like his approach would be my preference—steady, automatic payments, starting at (or even before!) birth, providing tangible support for families across the income spectrum. This would treat all parents equally, and all children equally, and could free up the EITC to be a more straight-forward subsidy for low-wage workers, rather than being tied to family and dependent status.

But some center-right thinkers worry that a too-generous child benefit could repeat some of the flaws of the Aid for Families with Dependent Children program, which was reformed in the 1990s. That could be a concern if benefits are too generous, but seems unlikely at the dollar amounts being discussed—Bruenig suggests a total of $4,480, or the difference between the federal poverty line for one person versus two in a family, paid over the course of 12 months— particularly if you believe the revisionist research on EITC and labor force participation published by Princeton’s Henrik Kleven.

Another concern is that a small number of low-income single moms would end up worse off. While valid, this edge case seems relatively trivial compared to the gains of having a less administratively burdensome approach to family benefits—currently, about one-fifth of EITC-eligible workers fail to claim their benefits. Some kind of additional payment to this subgroup for an interim period, as the Niskanen Center suggests, may be politically necessary.

Continuing to couch family benefits in a “tax credit” framework, no matter how attenuated, might be more politically palatable than the up-front monthly benefit Bruenig suggests, even if the “tax refund” framework adds complexity—recall that that even the ACA’s exchanges are constructed as “Advance Premium Tax Credits.” Eliminating claw-back or overpayment penalties could be a back-door way of ensuring parents who see their income change over the year aren’t penalized. The goal should be a system that is as universal and administratively simple as possible; and if a sense of fairness makes us want to avoid giving high-income parents benefits they don’t need, taxes at the very upper end could be nudged up to compensate for the extra benefit rather than the current clunky phase-out.

It’s not outside the realm of possibility for some conservatives to join forces on an expanded child benefit. The initial CTC proposal came from the National Commission on Children, established under the waning years of the Reagan administration. Using the tax code to support at-risk families, as the Commission’s gauzily-titled 1991 report, Beyond Rhetoric, declared, could garner bipartisan support at a time of “greater emphasis on family values and effective government intervention.”

As Joshua T. McCabe details in his highly-relevant book, The Fiscalization of Social Policy, the initial anti-poverty thrust of the CTC took on the logic of “tax relief” during the Gingrich Revolution. This helped win over conservative pro-family activists; at a crucial point, they flooded then-House Budget Chairman John Kasich’s office with phone calls, convincing him of the CTC’s political utility. As conservative political strategist Ralph Reed later noted, its inclusion in the 1997 balanced budget was the first time social conservatives had been able to “infringe on the turf of the economic wing of the Republican party,” which had traditionally held the whip hand.

Of course, the reign of the socially moderate, fiscally conservative Republicans is over. But it remains to be seen whether the post-Trump GOP, flailing for any sort of consistent identity, might find new purpose in standing athwart any President Biden proposal yelling stop, or come to the table to negotiate an authentically pro-family relief package.

Some unsolicited advice for the new administration: in hammering Biden’s proposal into legislative text, don’t be afraid to dream a little bigger. Make the expanded CTC permanent, instead of a one-year boost, and make it a monthly, universal child benefit, along the lines of what Bruenig (and I, as far back as February 2016) have proposed. Media reports suggest the Biden administration may indeed be moving this direction. (Also, scrap the ill-conceived child care reimbursement credit while you’re at it.) And dare the GOP to make good on its newfound self-conception as a multi-ethnic, working-class party, one whose economic and political interests would be ill-suited by objecting to putting more money in the pockets of working-class parents.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a former Sr. Policy Advisor to Congress’ Joint Economic Committee and a policy fellow with the Institute for Family Studies.

*Photo credit: Louis Velazquez on Unsplash