Highlights

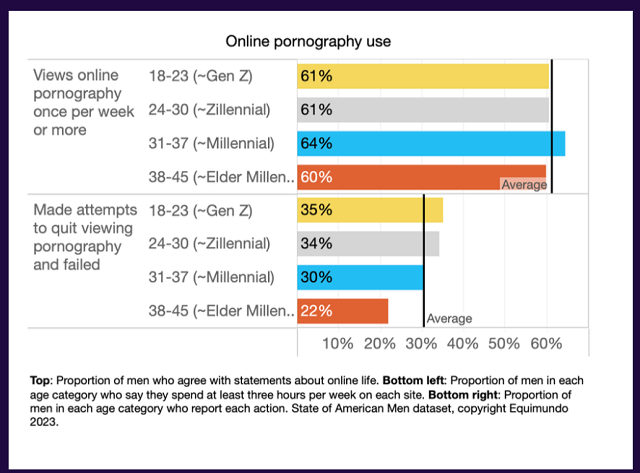

- Regular pornography consumption by men is high at around 60% for all age levels. Post This

- Many men have retreated into a virtual world, saying that their online life is more meaningful than their actual, real-world life. Post This

- Masculinity is not a problem to be solved, as Equimundo seems to think, but a way of being that needs to be channeled in directions that are both good for men and society. Post This

The troubles plaguing American men and boys have become so obvious that acknowledging them, and the problems they pose for society, is now a bi-partisan mainstream consensus. Even on the left, which has traditionally been more attuned to women’s issues, men’s troubles are capturing attention. We see this, for example, on the center-left in the work of Richard Reeves and his American Institute for Boys and Men.

We also see it in further left groups, such as a 2023 report, State of American Men, by the feminist organization Equimundo, a US NGO with roots in Brazil whose mission is “to engage men and boys as allies in gender equality.” Equimundo’s funders include the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and Archewell, the charity of the Duke and Duchess of Sussex.

One positive features of the report is a handy one-pager listing various statistics that show the problems facing men and boys today, including gender gaps in life expectancy, suicide, and educational attainment. I’ve never seen anything like this elsewhere.

But the bulk of the report consists of results from Equimundo’s own survey of Millennial and Gen Z men. They find that 40% of men report symptoms of depression. The younger cohorts seem more challenged than older ones, with ages 18-23 registering as the least optimistic. Almost two-thirds report that “no one really knows me well.”

Many men have also retreated into a virtual world, saying that their online life is more meaningful than their actual, real-world life. And, of course, many are struggling romantically: regular pornography consumption is high at around 60% for all age levels.

The report also confirms that there’s a class element at work. Those with higher educational attainment are more likely to exercise, engage in creative activities, participate in religious activities, and volunteer. Those with a masters’ degree or more scored highest in all those categories, whereas those with just a high school diploma or less scored the lowest.

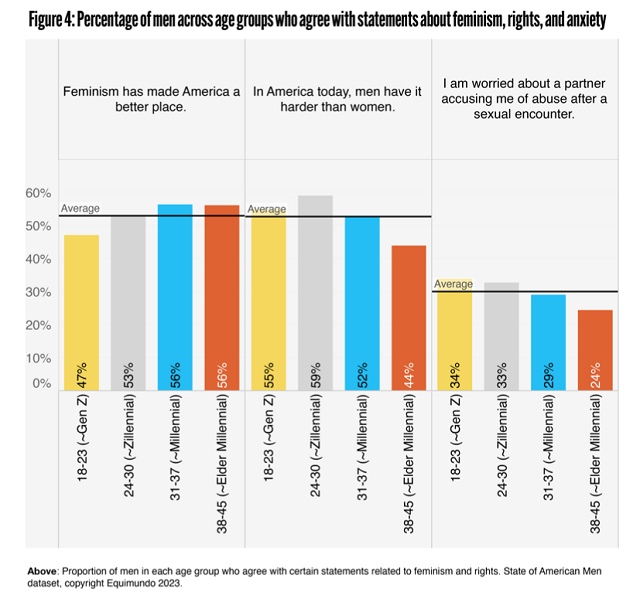

The researchers are particularly alarmed that young men are turning against feminism. The number of men agreeing that feminism made America a better place fell by nine percentage points between the 38-45-year-old group (56%) and the 18-23-year-old group (47%). Younger men are also much more worried about being accused of abuse after a sexual encounter—with rates up by about 50% between the older and younger groups; a bit over a third of 18-23-year-olds have this fear. And young men are increasingly putting their trust in online influencers. Perhaps the most eyebrow-raising finding in the report is that more 18-23-year-old men trust Andrew Tate than Joe Biden.

As a feminist NGO, Equimundo is keen for men to escape what they call the “Man Box” or traditional masculinity, in favor of female allyship. (The “Man Box” is defined in a previous report as something of a caricatured masculinity involving such traits as “acting tough,” “adhering to rigid gender roles,” and “using aggression to solve conflicts.”) But the report exhibits many of the same defects that conservative groups, like churches, have when it comes to reaching men, as I discussed in my Wall Street Journal article on why men prefer online influencers over traditional authorities.

I note that online influencers treat men as important ends in their own right, not just as means. And they want to help men achieve their own hopes, dreams, and plans. But Equimundo treats men primarily as instruments, wanting them to become allies in support of their own cause. Equimundo also appears to view men primarily as objects of therapeutic reconstruction rather than people with their own ideas about what they want out of life (something, by the way, the researchers did not ask about). Equimundo wants to redefine masculinity, for example, even at the expense of taking away men’s sense of purpose; those who hold to their dreaded “Man Box” have the highest sense of purpose in life, according to the survey.

To be clear, some purposes are bad, and men should not be affirmed in them. We should reject pickup artistry or the Andrew Tate vision of life. It is the role of societal authorities to point men especially towards higher aspirations. This is what Jordan Peterson at his best was able to do.

At the same time, we should take the flourishing of other people seriously, not subordinate their legitimate aspirations to serve our own aims. Masculinity is not a problem to be solved, as Equimundo seems to think, but a way of being that needs to be channeled in directions that are both good for men themselves and for society. We do need a more expansive vision of what it means to be a man, but replacing the “Man Box” with a different yet highly restrictive and less natural idea of masculinity is not the answer.

Aaron M. Renn is a co-founder and Senior Fellow at American Reformer. His writings appear at aaronrenn.com.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.