Highlights

- Some of the most interesting parts of the Family Almanac offer descriptive frameworks many people might have never considered. Post This

- Those concerned about falling fertility rates should first be concerned with declining marriage rates and how to reduce economic and cultural pressures that push marriage ever later. Post This

- The Almanac’s straightforward approach makes it a handy reference guide, ensuring that discussions of family policy have a grounding in what’s going on. Post This

It’s a good time to be talking about family policy in America. For too long, conservatives have ceded the playing field to progressives, treating discussions of family policy as envy of Scandinavia or purported social engineering.

But a growing concern about falling birth rates, declining rates of marriage, and a growing unease about the burdens on America’s parents have led many conservatives to take family-oriented public policy seriously. The flowering of rhetoric and ideas around ensuring that families are at the center of our economy is genuinely laudable.

But these discussions must be grounded in fact. In painting a picture of challenges facing American parents and their children, some on the populist right, as well as some on the left, overreach. The problems facing American families are real, but they are not existential. At the same time, those in elite policy circles often discount some of the bigger pressures on American families because they are ideologically inconvenient.

Our family policy discussions would benefit from operating from a common set of facts. But much of the data related to family economic security and other aspects of family life is scattered across government agencies. An aspiring politician should propose an Office of Family Life to marshal all the data, which in many cases already exists in different areas across the federal government, in a simple, easy-to-use website.

But until then, the Ethics and Public Policy Center’s 2022 Family Almanac will have to suffice. The Almanac is a no-frills, just-the-facts report I compiled for EPPC, intended to be a one-stop resource for policymakers, pundits, and the general public. With all of the contemporary discussions around family policy, there is increasing need for common ground in assessing the well-being of American families. In short, it’s intended to be almost everything you ever wanted to know about family life in America—but were afraid to ask.

The figures that make up the Family Almanac are presented as-is, with no interpretation, letting the reader take his or her own understanding away from the 83 charts across eight categories. Nearly all the graphs are based on government data, with the remainder drawn from top-of-the-line research papers or think tanks. The Almanac’s straightforward approach makes it a handy reference guide, able to be dipped in and out of, ensuring that discussions of family policy have a grounding in what’s going on.

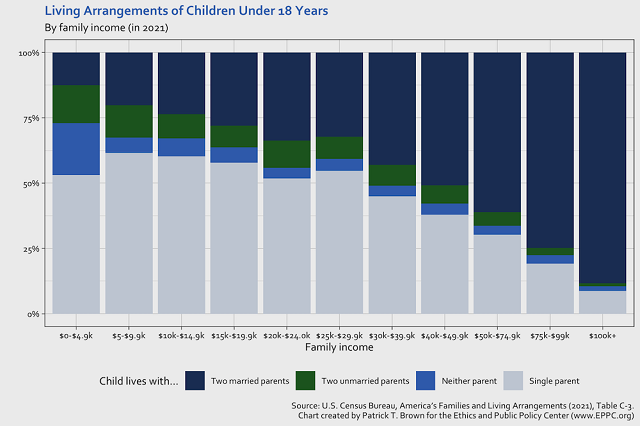

Many of the findings included in the Almanac will be familiar to readers of the Family Studies blog, such as the fact that marriage rates have been declining for decades before hitting rock-bottom during COVID, and that households made up of married, two-parent families have higher incomes and lower rates of poverty than single or cohabiting parents.

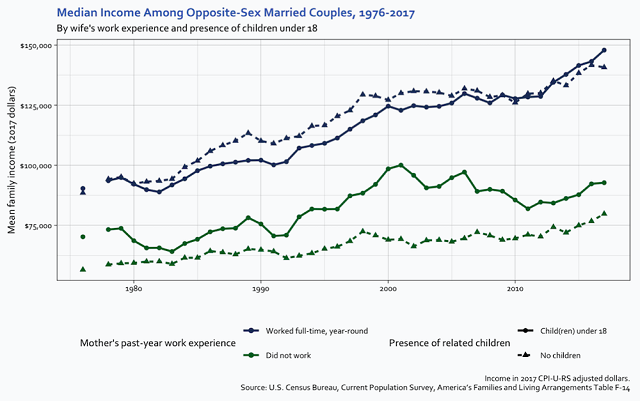

Other findings may be more surprising. For example, a full one-third of American families with kids are made up of married couples making over six figures, which might surprise those who assume a more declinist framework. The fertility rate among unmarried women peaked in 2008, before falling steadily since then, a major factor driving the nation’s fertility rate to all-time lows. And while family incomes have undoubtedly grown since the late 1970s, the growth has been steadier and faster for families with both parents working full-time, suggesting that families that prefer a male-breadwinner model may indeed be finding it harder to keep up.

And some of the most interesting parts of the Almanac offer descriptive frameworks many people might have never considered. In one-third of families made up of married couples with kids at home, the husband brings home about $50,000 or more in income than the wife; but in almost 20% of those households, the wife out-earns the husband. Median personal earnings among married fathers are about twice as high as cohabiting fathers. And since 1960, family spending on housing, health care, and child care has grown, while families are spending less (adjusted for inflation) on clothing and food.

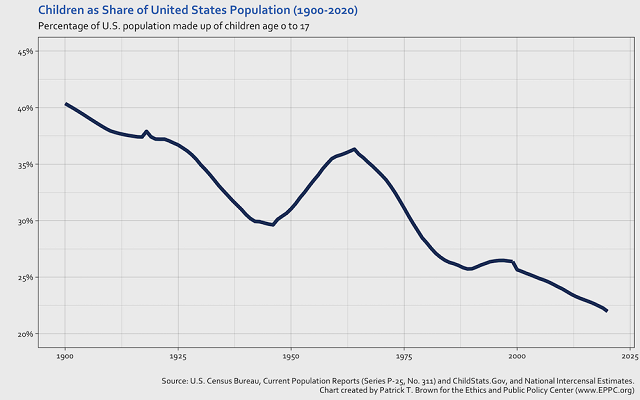

Perhaps the simplest way to understand the newfound energy around family policy is a chart that looks at children aged 0 to 17 as a percentage of the U.S. population (see chart below). Much of the decline is attributable to growing life expectancy; seniors can expect to live longer, healthier lives than they did in the first half of the 20th century. But the sheer fact remains—4 out of 10 Americans were under age 18 in the ambitious, tumultuous turn of the century. After World War II, the percentage of the population that was under 18 climbed again to over 35%, helping explain the cultural hegemony of Baby Boomers and their development of a distinctive youth culture. Now, the share of Americans under age 18 is dropping perilously close to 1 in 5, a sign of a greying—some might say decadent—population needing an injection of youthful enthusiasm.

As the Almanac illustrates, married fertility is still relatively resilient. So those concerned about falling fertility rates should first be concerned with declining marriage rates and how to reduce economic and cultural pressures that push marriage ever later. Beyond that, a family policy agenda will be strongest when it responds to real failures and pressure points on parents. The EPPC Family Almanac offers 83 little glimpses into what American families look like, and the circumstances they face. As more and more red-blooded populists and well-credentialed eggheads start developing ideas for family policy, these facts and figures are ready to help make sure the discussion is grounded in reality.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He writes from Columbia, S.C.