Highlights

- For women born in 1940, those with the highest accumulated incomes had the lowest average levels of fertility at age 50. This changed in subsequent cohorts who were beneficiaries of the expanded Swedish welfare state. Post This

- In Sweden at least, the paradox of richer people having the fewest children seems to be becoming a thing of the past. Post This

- The change from a negative to a positive relationship between accumulated income and fertility was only evident for women. Post This

“I will surely bless you and make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and as the sand on the seashore.” — (Genesis 22:17)

This quote from the Bible reminds us that in many cultures past and present, including ancient Judaism, numerous children are considered a great blessing. Yet while numerous children can be considered a blessing, in all cultures they cost time and resources to raise. Thus, it seems a paradox that people in the richest countries in the world where incomes are the highest have the fewest children. Even within those richer countries, the best-educated women with presumably the best income prospects typically have the fewest children (the U.S., for example). There is also much evidence of a negative relationship between personal income and the number of children for women, driven in part by the higher fertility of women who are not in the labor force.

But in Sweden this appears to be changing. In new research published in Population Studies, Martin Kolk examined the relationship between personal income and fertility for Swedish women and men born from 1940 to 1970. These cohorts witnessed the rise of a dual-earner society and an extensive welfare state in Sweden. Kolk measured personal income in two ways. First, he used personal income net of taxes in inflation-adjusted Swedish kronor, accumulated over the life-course up to age 50. This measure includes the many provisions of the Swedish welfare state, including generous paid parental leave that includes 80-90% of pre-childbirth wages. Second, he used life-course accumulated pre-tax earnings that did not include any benefits or transfers.

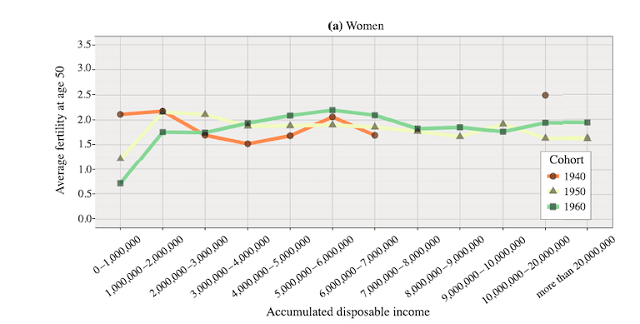

He found that for women born in 1940, those women with the highest accumulated incomes (including transfers and benefits) had the lowest average levels of fertility as measured at age 50 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

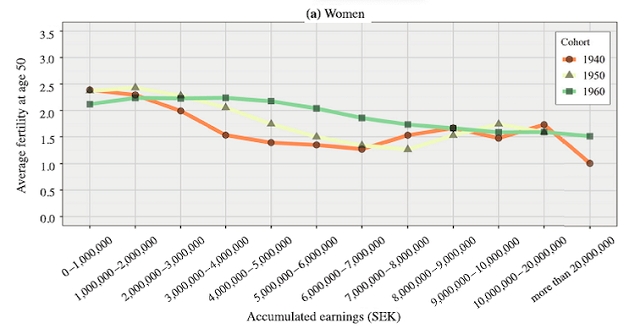

This changed in subsequent cohorts who were beneficiaries of the expanded Swedish welfare state, so there was a less negative relationship between accumulated income and fertility for women born in 1950, and for women born in 1960, there was a clear positive relationship between accumulated income and fertility. Most of the positive relationship was due to the low accumulated incomes of women with no children. The difference between the birth cohorts was also evident when income was measured as earnings from work, although the overall relationship between earnings from work and fertility remained negative, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

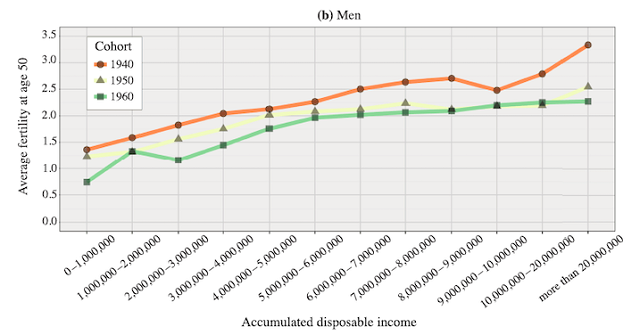

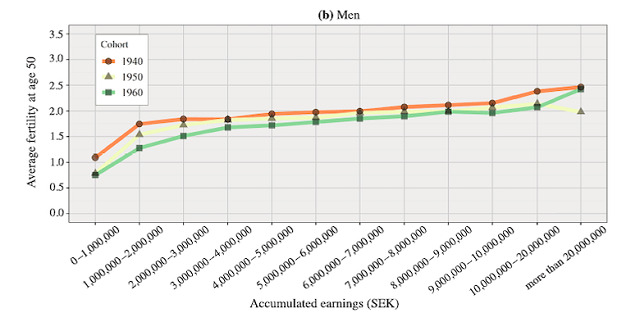

However, this change from a negative to a positive relationship between accumulated income and fertility was only evident for women. For men in all cohorts from 1940 to 1960, there was a strong positive association between both accumulated income and earnings with fertility (see Figures 3 and 4). Most of this positive relationship was due to the high accumulated income of men with more than two children and the low accumulated income of men with no children, something that that has also been found in other rich countries, including the U.S.1

Figure 3

Figure 4

These results suggest that while earning more money in the workplace serves to limit fertility for women, it does not do so for men; in fact, the opposite is true. But when the state provides ample benefits, such as income substitution during parental leave and child allowances, then high-income women (and not just high-income men) also have higher fertility than low-income women and men. This is because high-income women can relatively easily combine childbearing with employment, and the opportunity costs of childbearing in the form of lost income are slight. In the context of contemporary Swedish society, the earnings of both partners in a couple are considered essential for economic security. Poorly educated, lower-income women are more likely to have unstable employment and insecure economic situations, and they are more likely to be (often tenuously) partnered with similar men.

Both economic insecurity and partnership instability have increased rates of childlessness among lower-income women in Sweden.2 Better educated, higher-income women are more likely to have stable employment and are more likely to be partnered with better educated, higher-income men, and the greater economic security and stability of these partnerships promotes fertility. In Sweden at least, the paradox of richer people having the fewest children seems to be becoming a thing of the past.

As other rich countries copy the Swedish example of generous benefits for working parents, the same thing may also become true elsewhere. While this may appear to be an attractive outcome, it also suggests that the primary beneficiaries of generous Swedish benefits for parents are the highest earning men and women. Such an outcome seems antithetical to the rationale for the creation of an extensive welfare state in the first place.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life, (Routledge 2016) and editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018).

1. Hopcroft, R. L. 2006. “Sex, status and reproductive success in the contemporary U.S.” Evolution and Human Behavior27: 104-120; Nettle, D., and T. V. Pollet. 2008. "Natural selection on male wealth in humans." The American Naturalist 172 (5):658–66; Barthold, J. A., M. Myrskylä, and O. R. Jones. 2012. "Childlessness drives the sex difference in the association between income and reproductive success of modern Europeans." Evolution and Human Behavior 33:628–38.

2. Jalovaara, M., Neyer, G., Andersson, G. et al. 2019. "Education, Gender, and Cohort Fertility in the Nordic Countries." European Journal of Population 35, 563–586 (2019).