Executive Summary

America is facing a mental health crisis. Suicide, anxiety, depression, and drug overdose deaths have all risen to record levels. Younger generations have been hit especially hard during this crisis. Millennial men and women experience increased anxiety and depression compared to previous generations at the same age.

Some argue that the emotional state of young adults today is related to their financial precarity. Economic pressures such as student loans add stress in young adults’ lives, and Millennials have also encountered many obstacles in the workforce, including a challenging job market and longer work hours.

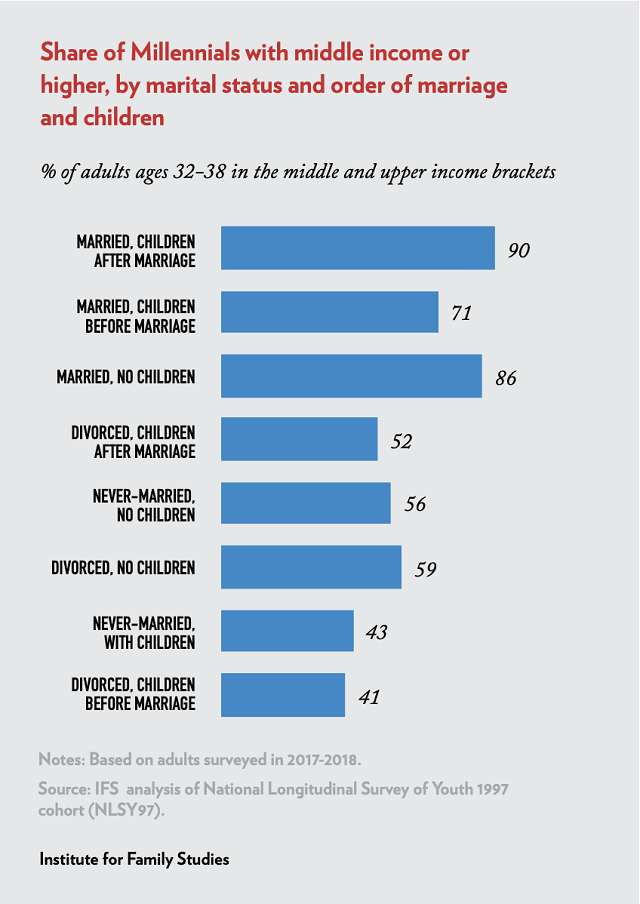

Meanwhile, there is a path that young adults who aspire to move up the economic ladder and establish a financially secure foundation should follow: Get at least a high school education, work full-time, and marry before having children. Among Millennials who followed what is known as the Success Sequence, 97% are not poor when they reach adulthood, and 90% reach the middle class or higher. Young adults who manage to follow this sequence—even in the face of various disadvantages—are much more likely to flourish financially.

In addition to offering robust financial benefits, could the Success Sequence also help young adults flourish emotionally and achieve better mental health outcomes? Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), a new report from the Institute for Family Studies explores the link between the Success Sequence and mental health among young adults when they reach their mid-30s.

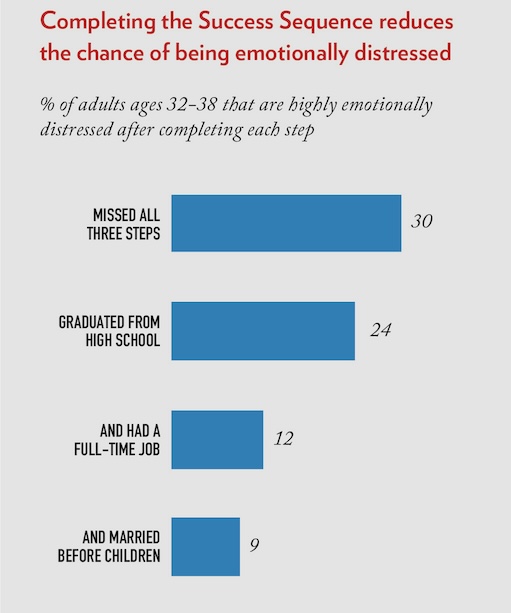

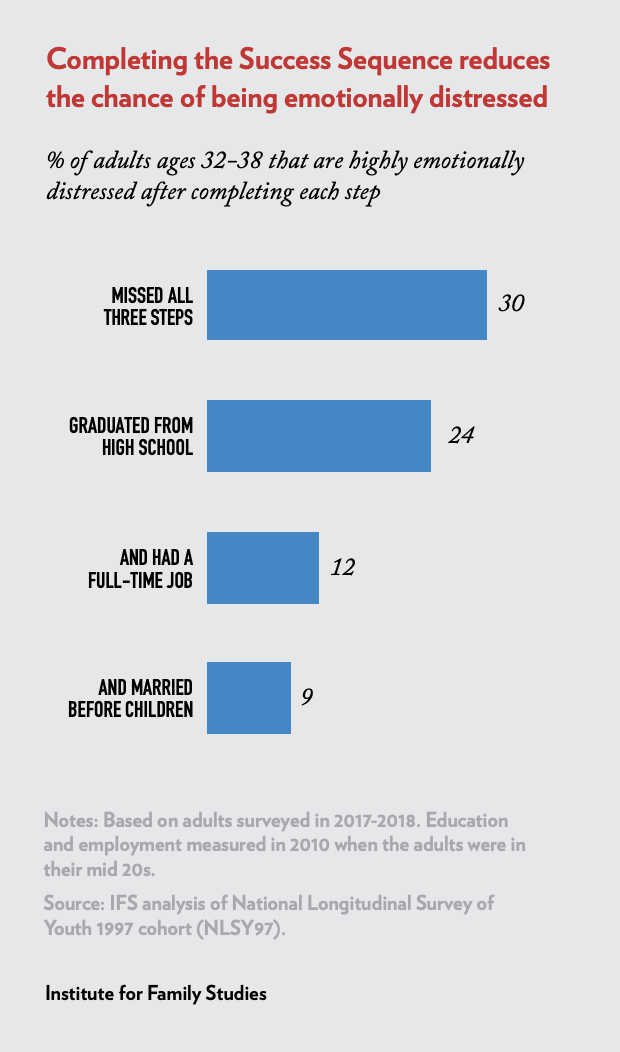

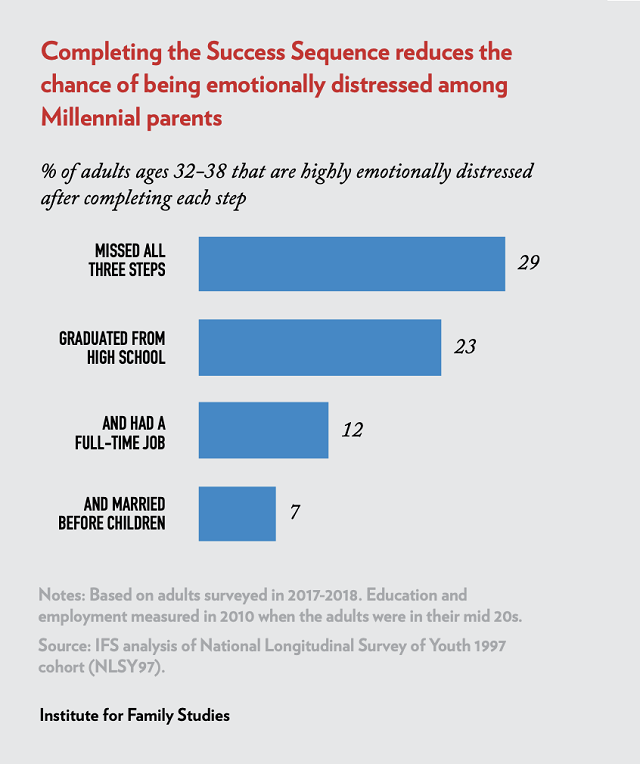

We find that the Success Sequence is strongly linked to better mental health among young adults. Our analysis of the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) in the NLSY97 demonstrates that the incidence of high mental distress at ages 32 to 38 drops dramatically with each completed step of the sequence. Millennials who completed all three steps are much less likely to be highly emotionally distressed by their mid-30s, compared with those who missed these steps (9% vs. 30%).

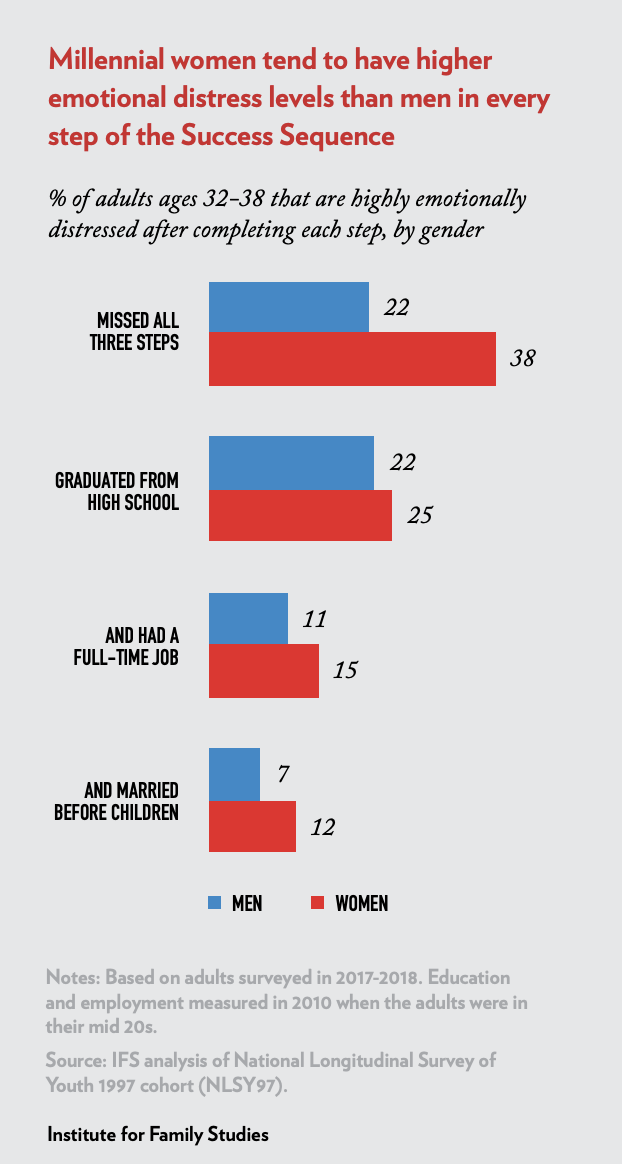

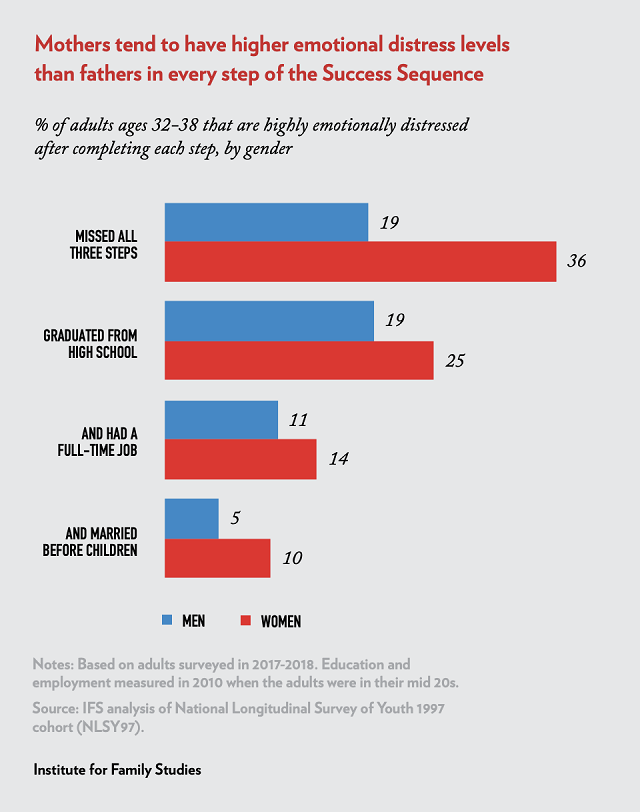

At the same time, there is a gender gap in mental distress among Millennials. Women are consistently more likely than men to report experiencing emotional distress. The gender gap is the largest among Millennials who missed all three steps of the Success Sequence (38% vs. 22%). But even among those who followed all three steps, women are still more likely than men to experience higher emotional distress (12% vs. 7%).

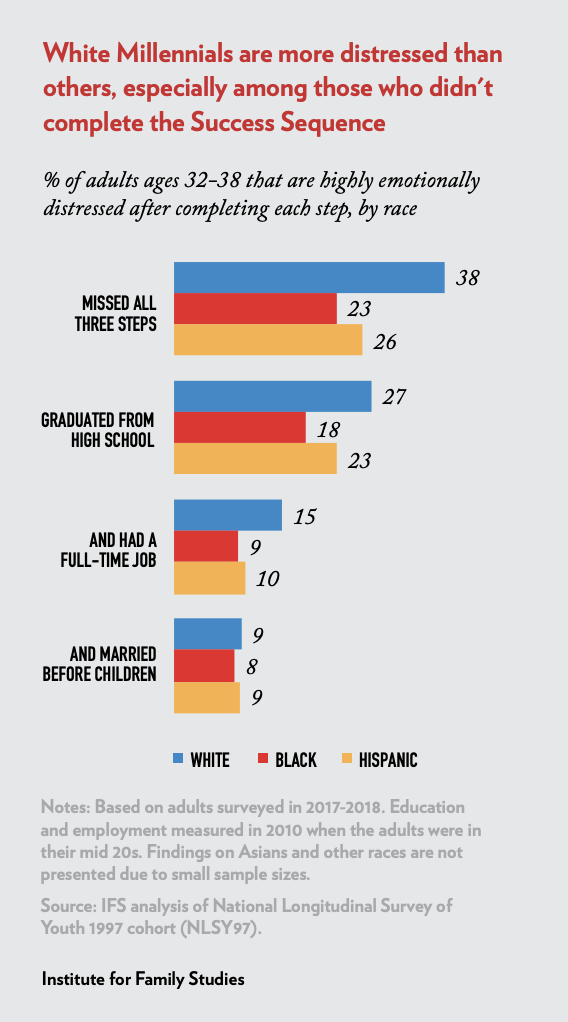

A racial gap also exists in mental distress among Millennials. White young adults who missed all three steps of the sequence by their mid-30s seem especially more likely to suffer from mental distress than other racial groups. Among this group, 38% of white young adults reported being highly emotionally distressed, compared with 23% of black and 26% of Hispanic young adults. This racial gap narrows with the completion of each step of the Success Sequence and is almost closed among young adults who have completed all three steps.

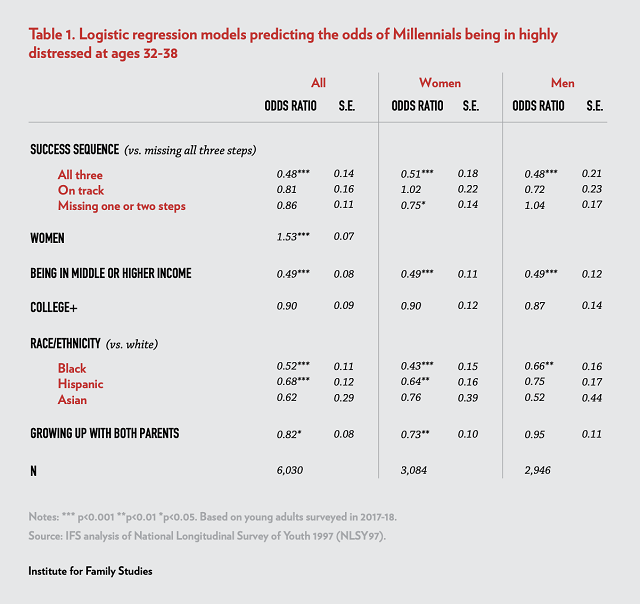

It is tempting to link better mental health to the financial success of the young adults who completed the Success Sequence, but the findings suggest that even after controlling for income, the sequence remains a significant factor in predicting your adult mental health. The odds of experiencing high emotional distress by their mid-30s are reduced by about 50% for young adults who have completed the three steps of the Success Sequence, after controlling for their income and a range of background factors, including gender, race, and family background.

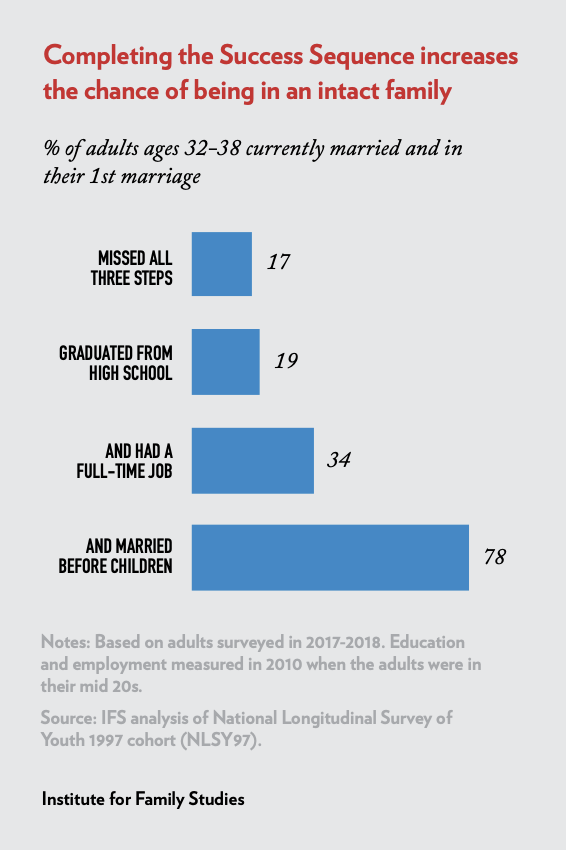

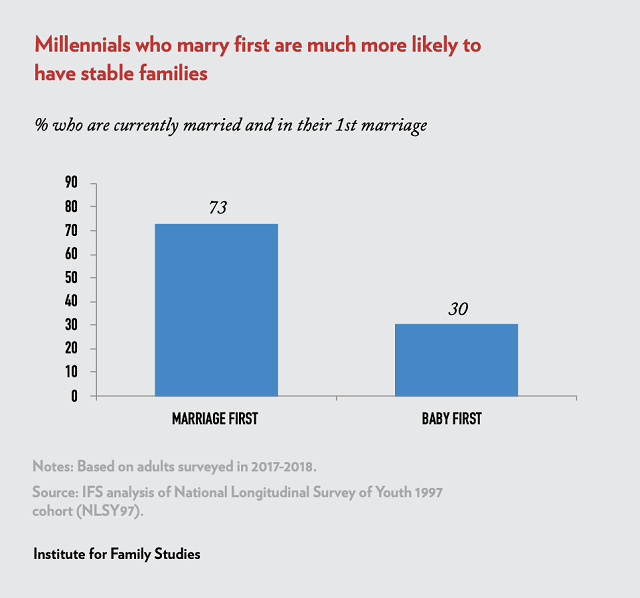

Why does the Success Sequence contribute to better mental health? Further analysis suggests that the sequence is closely linked to family stability, which is key to mental well-being. Millennials who married before having children are more likely to have stable marriages. Among Millennials who followed this path, 73% are in intact families (married and never divorced) by their mid-30s, compared with only 30% of those who had children before or outside of marriage.

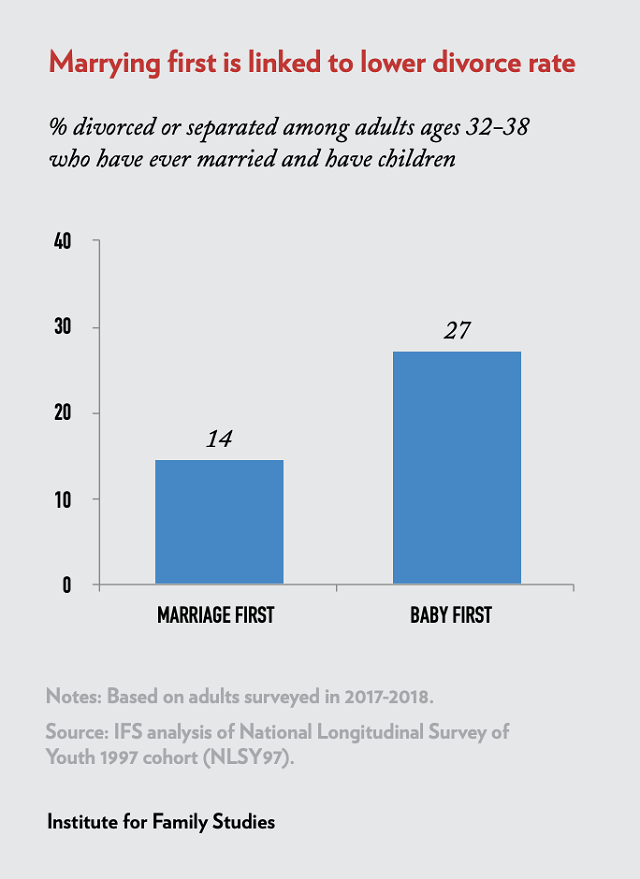

Furthermore, among Millennials who have been married and have children, those who became parents before marriage are about twice as likely to be divorced or separated by their mid-30s compared with their peers who married before having children (27% vs. 14%). Even after controlling for confounding factors like education, race, and family background, we find that marrying before having children is linked to a 32% decline in divorce among those who have ever married and have children.

Among the report’s other key findings:

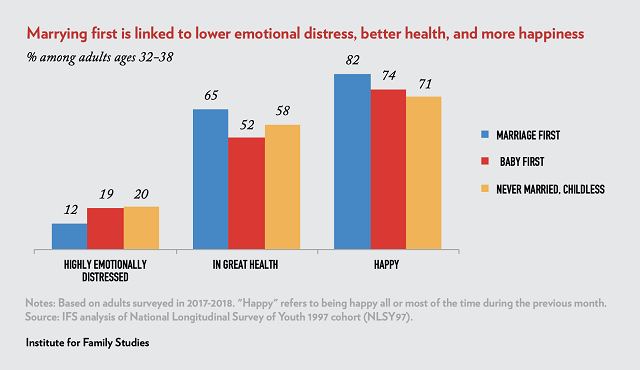

- The order of marriage and parenthood plays an important role in young adults’ overall well-being. Marrying before having children is not only linked to a lower risk of emotional distress but also to better general health and overall happiness. Millennials who married before having children are less likely to experience high emotional distress by their mid-30s compared with those who had a baby first (12% vs. 19%). They are also more likely to report being in great health (65% vs. 52%) and feeling happy all or most of the time (82% vs. 74%).

- Millennials who have never married and are childless by their mid-30s (about one in five) report higher levels of mental distress compared with those who followed the path of marrying before having children (20% vs. 12%). They are also less likely to report being happy (71% vs. 82%).

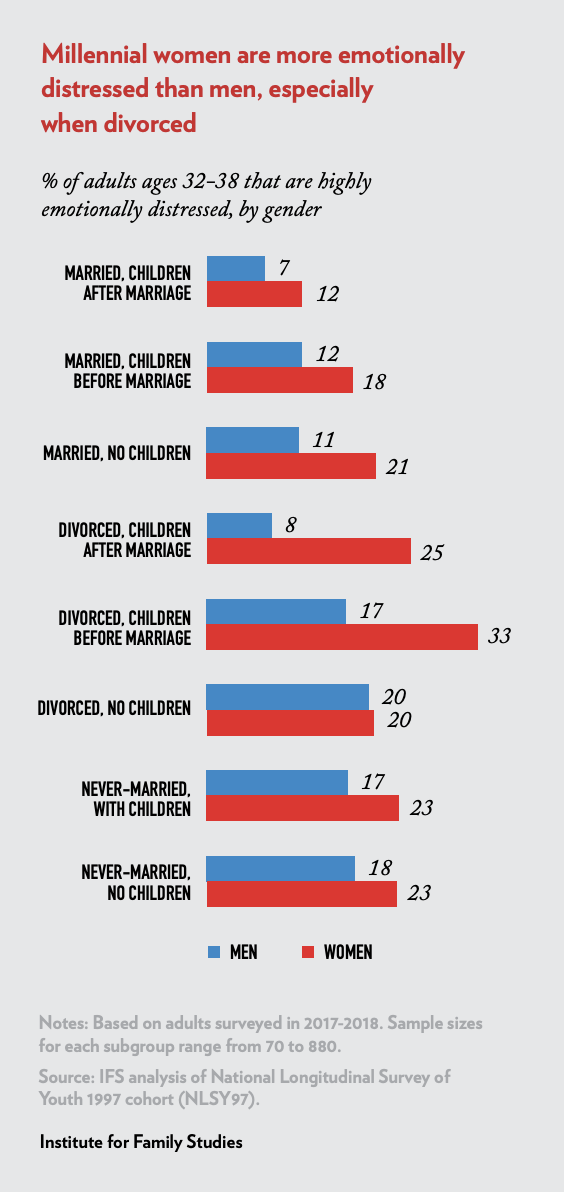

- Among Millennial women in their mid-30s, those who are currently divorced and had children before marriage experience the highest rate of mental distress (33%). In contrast, those who are currently married and had their children after marriage experience the lowest level (12%). About 21% of married, childless women experience higher levels of mental distress, as do 23% of never-married, childless Millennial women.

Data and methodology

Findings in this report are based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 cohort (NLSY97).

NLSY97 follows the lives of a national representative sample of American youth (with black and Hispanic youth oversamples) born between 1980 to 1984. This cohort is also considered the oldest group of Millennials. The survey started in 1997, when the respondents (about 9,000) were ages 12 to 17. The interviews were conducted annually from 1997 to 2011 and biennially since then.

Respondents who stayed in Round 18 (N=6,734) are spotlighted in this report. They were in their mid-30s (ages 32-38) when surveyed in 2017 to 2018. The findings are weighted to reflect the characteristics of the overall population of American Millennials who were born between 1980 and 1984. The minimal sample size for the subgroup analysis is 100 unless otherwise noted.

To measure mental health, a five-item short version of the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) in NLSY97 was used. The items of the MHI-5 measure risks for suffering anxiety and depression, loss of behavioral or emotional control, and overall psychological well-being. Respondents were asked about how they felt during the previous month through a set of 5 questions, which include feeling nervous, feeling calm and peaceful, feeling downhearted and blue, being happy, and feeling so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer them up. Each question was rated on a 4-point scale: (1) All of the time, (2) Most of the time, (3) Some of the time, and (4) None of the time. The scores of the negative outcomes are reversely coded and scores of all five questions are combined into a mental health index range from 5 to 20. “Highly distressed” is coded as 1 standard deviation (S.D.) above the mean.

In the analysis of the Success Sequence, finishing high school and having a full-time job (working 35+ hours per week and 50+weeks a year) were measured when respondents were in their mid-20s. For more details about the methodology of the Success Sequence, please see the report The Millennial Success Sequence.

Terminology

In this report, the term “Millennials” refers to adults born between 1980 and 1984, representing the oldest group of Millennials. The terms “Millennials” and “young adults” are used interchangeably, as are “mentally distressed” and “emotionally distressed.”

chapter 1: Navigating the Journey to Adulthood: Marriage, Parenthood, and Mental Health

The paths into adulthood for Millennials are more diverse than those of earlier generations. By their mid-30s, 45% of Millennials have married without first having a child, compared with about 70% of Baby Boomers when they were about the same age. Additionally, 35% of Millennials in this study have had children before or outside of marriage (compared to about 20% of Baby Boomers at the same age), and the remaining 20% of Millennials have never been married and are childless at ages 32 to 38.

Among young adults who are parents, there is almost an even split regarding the paths to parenthood. About 51% of Millennial parents in their mid-30s had children before or outside of marriage, while 49% took the path of getting married first before having children.

The order of marriage and parenthood matters for young adults’ health. Compared with their peers who had a child before marriage, Millennials who followed the path of “marriage first” are less likely to experience emotional stress and more likely to report being in great health and happy by the time they are in their mid 30s.1 For example, only 12% of Millennials who married before having a child report a high level of emotional stress, which is measured by a combination of mental health measures including depression, anxiety, and overall psychological well-being. In comparison, 19% of Millennials who had babies before marriage report a higher level of mental distress. Moreover, the group of Millennials who have never married and are childless report similar levels of mental distress as those who had babies before or outside of marriage.

Marrying first is not only linked to a lower chance of emotional distress, but also to better general health and overall happiness. Millennials who married before having children are more likely than those who had children first to report being in great overall health when reaching their mid-30s (65% vs. 52%) and being happy all or most of the time (82% vs. 74%).

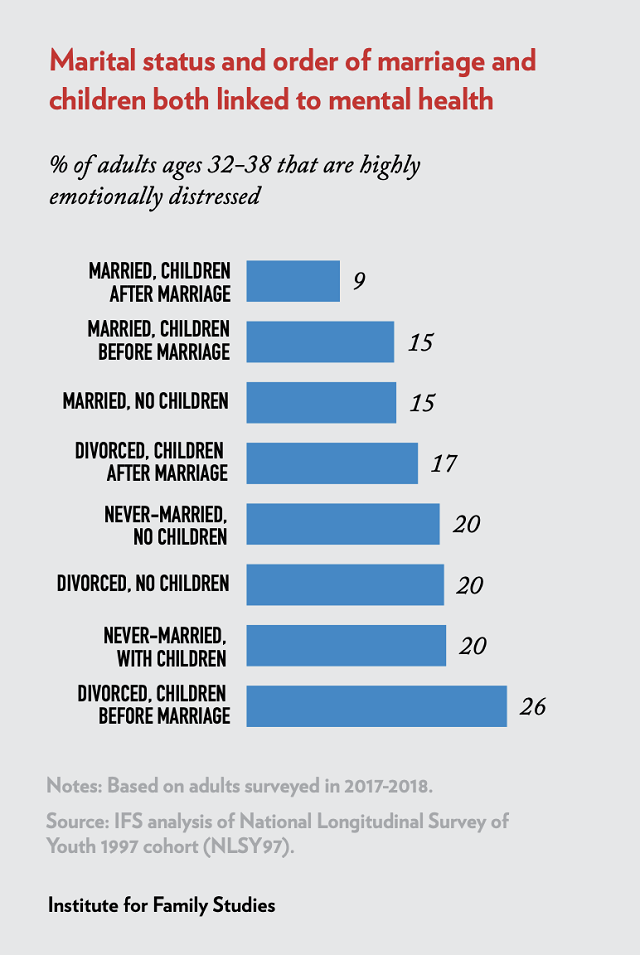

A closer look at different approaches to marriage and parenthood for Millennials in their 30s suggests that those who are currently married and had children after marriage have the lowest level of mental distress. Less than 10% of these adults reported high emotional stress, compared with 15% of Millennials who are married but either had children before marriage or are currently childless.

Divorce takes a toll on mental health. However, even among divorced young adults, the order of children and marriage is still linked to better mental well-being. Some 17% of divorced Millennials who became parents after marriage are highly stressed emotionally, compared with 26% of their peers who had children before marriage.

Millennials in their mid-30s who delay both marriage and parenthood (never married, childless) are equally likely to be emotionally stressed as their peers who have children but are not married. About 1 in 5 Millennials in these two groups experience high-level emotional distress, as do their peers who are divorced but do not have children.

These findings regarding mental health echo some of the results about Millennials’ family and financial status. We find that married Millennials who have children after marriage are most likely to be in the middle- and upper-income brackets (see more details in the Appendix). However, married and childless Millennials are better off financially than married Millennials who had children before marriage, yet the emotional stress levels in these two groups are similar. We also find that divorced and childless individuals are also better off financially than divorced Millennials who had children after marriage, but they have slightly higher rates of emotional distress. These findings suggest higher family income and better mental health do not always go handin-hand, especially when it involves children and marriage.

Chapter 2: The Success Sequence and Mental Health

In addition to the order of marriage before having children, the Success Sequence includes two earlier steps: Getting at least a high school education and working full time. Our analysis finds that the Success Sequence is strongly linked to better mental health among young adults. For Millennials who complete all three steps of the sequence, the chance of being highly emotionally distressed is only 9% when they reach their mid-30s. In contrast, 30% of Millennials who missed all three steps are in mental distress at this life stage, and those who completed the education and work steps but didn’t marry before having a child are also more likely to be highly distressed (12%) when they are in their mid-30s.

It may seem logical to attribute better mental well-being to the financial success of young adults who followed the Success Sequence, but the findings suggest that even after controlling for income, the sequence remains a significant factor in the mental health of young adults. The odds of experiencing high emotional distress by their mid-30s are reduced by about 50% for young adults who have completed the three steps of the sequence, after controlling for a range of background factors including family income, education, gender, and race (see Table 1 in the Appendix for details).

To see exactly how the order of marriage and parenthood plays out for Millennials, we also looked at the impact of the Success Sequence among Millennials who have had children (about 70% of Millennials have had children by age 32 to 38). The findings are identical: Millennial parents who missed all three steps of the sequence are much more likely than others to experience mental distress. In contrast, the mental distress level is much lower, around 7%, among Millennial parents who have completed all three steps of the sequence (see figure in Appendix for more details).

Gender

Millennial women are consistently more likely than men to be emotionally distressed. Overall, about 19% of Millennial women in their mid-30s report high emotional stress, compared with 13% of Millennial men. Among Millennial women who missed all three Success Sequence steps, 38% are highly emotionally distressed at ages 32 to 38. The share is 22% for Millennial men who missed all three steps by their mid-30s. With the completion of each step of the Success Sequence, the emotional stress level generally goes down for both Millennial men and women, but the gender gap remains. Even among Millennials who have followed all three steps, women are still more likely than men to experience high emotional stress (12% vs.7%).

A similar gender gap also exists among Millennials who have children. Among Millennial parents who missed all three steps of the Success Sequence, 36% of mothers and 19% of fathers are highly emotionally distressed by their mid-30s. The gap is significantly reduced but remains among Millennial parents who have completed all three steps of the Success Sequence: only 5% of Millennial fathers and 10% of Millennial mothers who followed the sequence experience high mental distress by their mid-30s.

These findings are in line with longstanding patterns from psychiatry that women are more likely to suffer from anxiety or depression. Several potential reasons have been offered as to why women are more prone to emotional distress, including the fact that women experience more hormonal fluctuations that can trigger clinical depression or anxiety. For example, women are prone to particular forms of depression or anxiety that are specifically triggered by these hormonal changes, including premenstrual dysphoric disorder, postpartum depression, or postmenopausal depression or anxiety, whereas men do not experience these conditions.

Looking at the different family paths Millennial men and women have taken, we find that overall, married women who have children after marriage enjoy better mental health than other women, with only 12% of them experiencing high emotional stress in their mid-30s. On the other hand, divorced Millennial women who had children before marriage have the highest levels of mental distress by their mid-30s. About 1 in 3 divorced Millennial women who had children outside of marriage are highly distressed.

In contrast, divorced Millennial women who had children after marriage suffer less emotional distress. About 1 in 4 of these women reported being highly emotionally distressed. This is similar to the emotional distress levels among never-married women (with or without children).

Young men’s emotional distress levels are lower overall than that of young women in most of these different family paths, except among young adults who are divorced but childless. An equal share of young men and women (20%) in this group experience a high level of emotional distress, which represents the highest level of emotional distress among Millennial men in their mid-30s. Millennial men who are currently married and have children after marriage experience the lowest levels of mental distress. Interestingly, divorce doesn’t take a heavy toll on young men who are divorced but have children after marriage. Only 8% of men in this situation experience high emotional distress, which is similar to the rate for men who are married and had children after marriage.

Race/Ethnicity

In contrast to the financial success story presented in the previous IFS report on the Success Sequence, where white Millennials were consistently less likely than black and Hispanic Millennials to be in poverty, white Millennials do not have an advantage over other young adults when it comes to emotional well-being. In fact, they are generally more likely than other races to experience emotional distress.2 Among young adults who have missed all three steps of the sequence by the time they are in their 30s, white young adults are much more likely to report that they are highly emotionally stressed (38%) compared with black young adults (23%) and Hispanics (26%), despite the fact that white young adults in this situation are much less likely to be in poverty than the other two groups.

With completion of each step of the Success Sequence, the racial gap narrows. For Millennials who followed all three steps, the share of highly emotionally stressed young adults drops to 9% for whites, 8% for bBlacks, and 9% for Hispanics. The racial gap in emotional well-being is almost closed.

Previous studies on Millennial health showed that Millennials in majority black and Hispanic communities have significantly lower rates of depression than those in majority white communities, with some hypothesizing that these differences could be due to under-diagnosis in communities of color. Our analysis of NLSY data support a lower rate of symptoms of depression and anxiety among black and Hispanic individuals. Notably, the self-report nature of this data suggests that lower rates of depression and anxiety symptoms among black and Hispanic individuals may not be due to underdiagnosis and that other factors may be at play.

Taken together, the Success Sequence’s link to both economic success and emotional well-being suggests that following the sequence offers a clear path to closing the racial gap, not only in terms of economic well-being but emotional well-being as well.

Chapter 3: The Success Sequence and Family Stability

The Success Sequence benefits Millennials’ mental health not only through the financial success it brings but also because it is linked to another important factor in mental health: family stability.

Millennials who followed the sequence of marrying before having children are more likely to have stable marriages. Among Millennials who married before having children, 73% are in an intact family (married and have never been divorced) by the time they are in their mid-30s, compared with only 30% of Millennials who had children before or outside of marriage. Furthermore, among Millennials who have been married and have children, those who became parents before marriage are about twice as likely to be divorced or separated by the time they reach their mid-30s, compared with their peers who married before having children (27% vs. 14%).

Following all three steps of the Success Sequence—getting at least a high school education, working full-time, and marrying before having any children—leads to much higher family stability by the time Millennials reach their mid-30s. Close to 80% of young adults who followed this path are married and have never divorced, compared with 34% of young adults who missed the step of marrying before children, and 17% of young adults who missed all three steps.

Moreover, after controlling for a range of sociodemographic factors, young adults who followed the three steps of the Success Sequence are four times more likely to be living in an intact family in their 30s compared with their peers who didn’t follow the sequence. The fact that family stability is key to mental health is supported by multiple lines of research. For children, parental divorce is a large and consistent risk factor for anxiety, depression, and substance use. Family stability (as in marital stability without divorce) has repeatedly been shown to lead to better financial and educational outcomes for children, which in turn reduces the risk of mental health problems.3 Another key way that family stability may mediate improved mental health outcomes for children is by protecting them from physical and sexual abuse, which greatly increase the risk of psychiatric problems.4 Overall, children from families with married biological parents are three to 10 times less likely to experience physical abuse compared to children in step-families or in households headed by single parents with or without romantic partners; they are also five to 20 times less likely to experience sexual abuse.5

Family stability is also important for the mental health of adults. Reports based on large and nationally representative surveys have shown that both men and women who marry and remain married have lower rates of depression, anxiety, suicide, and suicide attempts compared to those who are single, widowed, or divorced.6 These findings parallel the conclusions of this research brief.

There are many contributing factors to mental health, but family stability is clearly a major factor. The findings of this report are in line with decades of research from psychology showing that relationships are fundamental to human happiness and well-being. Furthermore, among the many relationships that affect us, marital relationships tend to have the greatest bearing on our emotional (as well as physical) health.

The mere act of being married raises the probability that someone is very happy by a substantial amount. In a prior analysis of data (1972-2021) from the General Social Survey, 37% of those who were married reported they were very happy compared to 18% who were single, widowed, or divorced.

Lower Divorce Among Millenial Parents Who Married First

There are many potential ways that marrying before having children favors greater relationship stability compared to when the sequence is reversed. Divorce is one measurable indicator.

Divorce is a major stressor in life, and it is linked with an increased risk of anxiety, depression, and alcohol abuse, along with other negative mental health outcomes. When we limit the analysis to Millennials who have been married and have children, a clear pattern emerges regarding the order of marriage and having children and family stability. Millennials who became parents before getting married are about twice as likely to be divorced or separated by the time they are in their mid-30s, compared with their peers who married before having children (27% vs. 14%).7 Even after controlling for confounding factors like education, race, and family background, we find that marrying before having children is linked to a 32% decline in divorce among those who have ever married and have children.8

Both groups are married with children. But what explains why the group who had children before marriage is more likely to experience divorce than those who had children after they were married? Many factors could be at play. Couples who have children before marriage may not have fully established the foundation of their relationship, such as commitment and communication, which often leads to increased marital strain. Additionally, the stressors associated with unplanned pregnancies and early parenthood may exacerbate existing relationship challenges.

Moreover, our findings suggest that Millennials who become parents before marriage tend to have children at an earlier age than those who marry first (with a median age for first birth of 21 vs. 28), but they marry later than the “marriage first” group (at 26 vs. 24). With an extended gap between first birth and marriage, it is possible that some Millennials who follow this path may not necessarily marry the parent of their children, further complicating family relationships. These complexities in family dynamics could contribute to the increased likelihood of divorce among couples who had children before marriage.

Chapter 4: Conclusions and Implications

The Success Sequence—completing at least a high school education, securing full-time employment in their 20s, and marrying before having children—not only offers a promising path for young adults to achieve economic success but is also closely linked to emotional and mental well-being. Moreover, the ways in which the Success Sequence contributes to mental health are not limited to financial success but also to the higher levels of family stability associated with following this path.

Our findings demonstrate that young adults who’ve followed the three steps of the Success Sequence experience significantly better mental health by their mid-30s compared with those who have not. This is true even after accounting for various background factors such as income, gender, and race. The odds of experiencing high emotional distress are reduced by about 50% for those who have completed each step.

Family stability emerges as a crucial factor in the mental well-being of Millennials. Those who marry before having children are more likely to maintain intact families, with 73% remaining married by their mid-30s. In contrast, those who have children before marriage face much higher rates of divorce and separation. The extended gap between first birth and marriage in this group often complicates family relationships, potentially leading to greater family instability and subsequent mental health challenges.

Given the mental health crisis among Millennials and young adults, it is important for young people to understand what patterns are more likely to help them form families that lead to better mental health. Unfortunately, a variety of factors in contemporary culture have made it more difficult for young people to form stable marriages and families.

One factor is that marriage is less likely to be valued than work or education. A 2023 Pew Research Center report noted that 88% of parents agreed it was “very” or “extremely” important for their children to have an enjoyable job, and 41% said it was very or extremely important for their children to graduate from college, whereas only 20% of parents attached the same level of importance to their children getting married. These goals run in contrast to decades of sociological data that conclude a good marriage is more important to well-being than other factors, including career.9

This mismatch between those goals we tend to prioritize and what actually leads to enduring well-being occurs on an individual level as well. Predicting how we are going to feel in a given circumstance is known as affective forecasting. Humans make such predictions every day without thinking, and these predictions shape life priorities. Surprisingly, humans are relatively poor judges of what leads to enduring well-being.

Psychological science has repeatedly shown that relationships are the most important factor for well-being and happiness.10 The most important relationship is with one’s romantic partner or spouse. Helping young people understand the importance of relationships to well-being is critical to helping them prioritize marriage.

Today’s young adults receive ample training and guidance in education and career, but when it comes to getting married and having children, most people “just wing it.” Among the key components of the Success Sequence—education, work, marriage, and children—training and guidance on healthy marriages and family life are severely lacking.

As we suggested in previous reports, we should teach the Success Sequence in schools and promote it via public campaigns. For those who care about both the economic and emotional well-being of today’s young adults—policymakers, educators, business and community leaders, influencers, as well as parents—it is time to help young adults understand how following each step in the Success Sequence will increase their chances of a financially and emotionally healthy life.

Appendix

-

The “Marriage first” group includes those who had children after marriage, regardless of their current marital status, as well as those who are currently married but do not have children. The “Baby first” group includes those who had children before marriage or outside of marriage, regardless of their current marital status.

-

Overall, 17% of white Millennials in their mid-30s reported high emotional stress, compared with 14% of Black Millennials, 14% of Hispanic Millennials, and 11% of Asian Millennials, according to NLSY97 data.

-

David Blankenhorn. Fatherless America: Confronting Our Most Urgent Social Problem. (New York City: Harper Perennial, 1996); David Popenoe. Life Without Father: Compelling New Evidence That Fatherhood and Marriage Are Indispensable for the Good of Children and Society. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999). Also: Melissa Kearney. The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023).

-

Jutta Lindert, et al., “Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: A systematic review and metaanalysis.” International Journal of Public Health 59, no. 2 (2014): 359-372.

-

Felicitas Auersperg, et al., “Long-term effects of parental divorce on mental health: A meta-analysis.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 119 (2019): 107-115. Brad Wilcox. Get Married: Why Americans Must Defy the Elites, Forge Strong Families, and Save Civilization. (New York City: HarperCollins, 2024).

-

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. The Effects of Marriage on Health: A Synthesis of Recent Research Evidence. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, June 2007). Sohrab Iranpour, et al., “The trend and pattern of depression prevalence in the U.S.: Data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005 to 2016.” Journal of Affective Disorders 298, part A (February 2022): 508-515. W. KyungSook et al., “Marital status integration and suicide: A meta-analysis and meta-regression.” Social Science & Medicine, 197 (2018): 116-126. T.J. Bommersbach, “National trends of mental health care among US adults who attempted suicide in the past 12 months.” JAMA Psychiatry 79, no. 3 (2022): 219-231.

-

Marital status was measured at ages 32 to 38, accounting for multiple divorces and remarriages.

-

The regression model includes work status and whether the respondents lived with both of their parents during their teenage years.

-

Op. Cit, Wilcox. Get Married.

-

Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz. The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2023). M.E.P. Seligman. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. (New York: Atria Books, 2011).

About the Authors

Wendy R. Wang, Ph.D. is Director of Research at the Institute for Family Studies. She has published widely on topics including marriage, gender, work, family, happiness, and well-being. Dr. Wang is a former Senior Researcher at Pew Research Center and the lead author of the Pew Research Center report, Breadwinner Moms, among other Pew reports.

Samuel T. Wilkinson, MD, is Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine and the Associate Director of the Yale Depression Research Program. His research specializes in innovative treatments for depression, including novel pharmacological and neuromodulation techniques. Dr. Wilkinson is also the author of the book Purpose: What Evolution and Human Nature Imply about the Meaning of Our Existence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank IFS senior fellow Brad Wilcox for his insights and substantive feedback on this report. We would also like to thank Alysse ElHage for editing the report and Brandon Wooten for its design.