Highlights

- Not only do these findings tell us that marriage still matters for having babies, but marriage is the most important factor shaping fertility. Post This

- Both marital and nonmarital first birth rates have declined, though—on the whole—marital first birth rates remain very similar to where they were at any point between the 1970s and today. Post This

- A whopping 75% of the total fertility decline since 2007 is attributable to the shifting likelihood that people are married. Post This

With fertility falling around the world, many commentators and governments are scrambling to figure out why and what can be done. A recent Financial Times article, which heavily cited previous work at IFS and replicated some of our analyses, correctly pointed the finger at the main culprit the decline in fertility: falling marriage rates. Declining marriage is the proximate cause of falling fertility in many societies today.

This surprises many people, because, in the public’s imagination, nonmarital childbearing is running rampant, while marriage is becoming a thing of the past. In short, these impressions are wrong. In the U.S., the share of births born to unmarried parents is gradually drifting downwards these days. But more to the point, far from being a thing of the past, marriage remains overwhelmingly predictive of fertility behavior. Married people make more babies, and this is true all around the world, as we showed in a 2022 report.

This January, new evidence for the importance of marriage for understanding fertility became available. Since the 1950s, the U.S. government has run a series of family surveys which operate today as the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). The last wave available was a survey covering 2017-19. But the 2022-23 survey wave has now been released. These surveys include retrospective marriage and fertility data that allow us to ask a simple question: What are the odds a childless person had a first birth before a first marriage vs. after a first marriage? Put simply, how much does getting married increase the odds that women start having children?

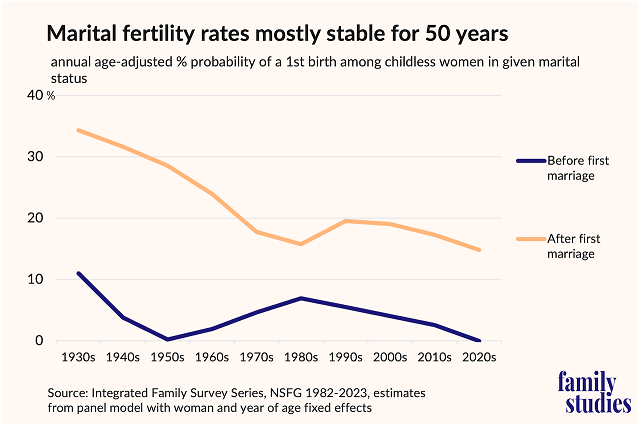

It’s important to focus on first births, since the lion’s share of fertility decline in the last 20 years has been due to rising childlessness and, thus, declining rates of first births. The figure below updates a figure we produced for the IFS report mentioned above to include the 2022-2023 NSFG survey respondents.

Marital first-birth rates dropped sharply between the 1930s and 1970s, even as nonmarital fertility rates dropped between the 1930s and 1950s, then rose between the 1950s and 1980s. As of the 1980s, it did look like maybe marriage was no longer important for family formation: unmarried women’s first birth rates were near historic highs, and married women’s at historic lows.

But in the 1990s, childless unmarried women started becoming less likely to have a first birth, especially due to falling teen birth rates. Meanwhile, marital first birth rates rose. In the ensuring decades, both marital and nonmarital first birth rates have declined, though, on the whole, marital first birth rates remain very similar to where they were at any point between the 1970s and today.

The key thing to note, however, is the gap. In the 2020s, the (modestly-sized) NSFG sample suggests unmarried women were extremely unlikely to have a first birth, whereas for married women without children, there was about a 15% probability of having children in the next year (with, of course, appreciable variation by age). In other words, marriage still predicts vastly higher fertility. Even today, though people sometimes report in surveys that marriage isn’t all that important for childbearing, the fact is people overwhelmingly prefer to be married before having children, and thus most delay pregnancy until they have a spouse. When it comes to having babies, marriage still matters.

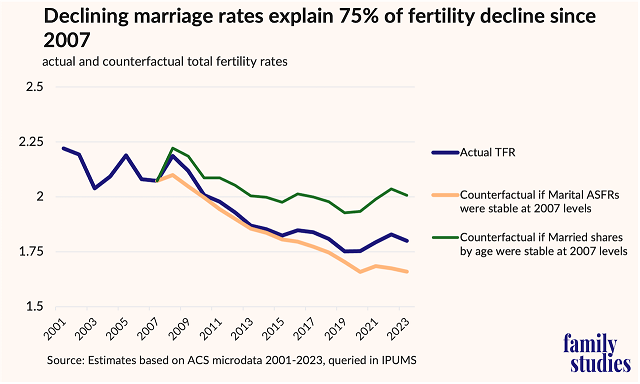

And in fact, declining marriage is by far the most important explanation for falling fertility writ large. The figure below uses data from the American Community Survey’s 2001-2023 fertility and marital status microdata, and shows three different fertility trajectories. The first is just the total fertility rate as measured by the ACS (not an exact fit for actual TFRs from vital statistics, but highly correlated). The second line shows what the total fertility rate would have been if marital fertility rates had stayed flat at their 2007 levels all the way to 2023. The third line shows what the total fertility rate would have been if age-specific married population shares had stayed flat at their 2007 levels until 2023.

Based on ACS data, if marital fertility rates had stayed stable after 2007, fertility today would actually be even lower: the combination of shifting age-specific fertility rates by marital status and the changing actual prevalence of marriage pushed marital births upwards, especially after 2015. On the other hand, if the share of people married by age had remained stable at 2007 levels, and birth rates within marriage had followed their actual historic trajectory, fertility rates today would be about 12% higher. In the ACS data, this means fertility would be at replacement level. A whopping 75% of the total fertility decline since 2007 is attributable to the shifting likelihood that people are married.

These findings tell us that, not only does marriage matter for having babies, but marriage is by far the most important factor shaping fertility. Nothing else is going to account for 75% of the observed change. And furthermore, married couples are not turning away from having children! As the orange line above shows, changes in the odds that married people choose to have kids just can’t explain almost any of the decline in fertility. When Americans today get married, they have babies just like married people at their ages did in the past. Explanations for falling fertility that place the blame on couples choosing not to have kids probably can’t explain much about declining fertility, since changes in within-couple behavior are not the main story!

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do more to help couples choose to have kids! Getting people to marry younger may prove difficult, expectations of having kids may shape marital behavior, and married people still overwhelmingly tend to undershoot their fertility goals. Even if declining marriage rates are the main cause, helping couples have more of the children they desire may be part of the solution. But it’s only part of it: the United States also needs a serious pro-marriage agenda that will dramatically improve the economic and social supports and opportunities for young people to pair off and start families.

Lyman Stone is Senior Fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.