Highlights

- Making birth free delivers assistance to families at the perfect time while reducing stressful interactions with America’s healthcare bureaucracy. Post This

- In addition to disproportionately failing to reach pregnant married mothers, Medicaid’s penalization of marriage likely prevents some portion of unions from forming in the first place. Post This

- Given the growing share of Americans that report not wanting to have children, it’s worth reflecting on whether we’ve structured policy in ways that make parenthood needlessly difficult. Post This

Is freeing parents from the financial cost of childbirth a worthwhile goal for public policy? In a recent essay for Compact Magazine, Catherine Glenn Foster of Americans United for Life and Kristen Day of Democrats for Life argue the affirmative case, pointing to the high costs and administrative hurdles that families often face during the course of giving birth in this country. To alleviate these burdens, they propose establishing a new program that would cover the complete cost of birth for all Americans, similar to the assistance that Medicare currently provides for sufferers of advanced kidney disease regardless of age. Yesterday, Allan Carlson made the historical case for this nationwide “affirmation of motherhood and babies.”

But not everyone is so sure that making birth free is the best way to help families. In their response to Foster and Day, published here two weeks ago, Leah Libresco Sargeant and Patrick T. Brown provided a sympathetic critique of the proposal. While they applaud the intent and creative design, they question whether fully eliminating the cost of birth is worth creating a new federal program. Given that 4 in 10 births are already free through Medicaid, they recommend that we instead direct our attention to more targeted reforms such as expanding Medicaid further.

If, however, we are looking for a policy that would support a more comprehensive set of pro-family aims, such as bolstering financially vulnerable families broadly, including ones with married parents, then making birth free is among the most attractive policies out there. Making birth free delivers assistance to families at the perfect time while reducing stressful interactions with America’s healthcare bureaucracy. This adds up to a pro-family outcome that’s very hard to beat, and there are multiple ways to get there.

No Better Time to Assist Families Than at the Birth of a Child

Before tackling the specifics of Leah and Patrick’s critique, it’s worth reiterating that reducing the financial costs and administrative hassles associated with pregnancy are among the best ways to assist families. Forgone spending on pregnancy-related co-pays and co-insurance translates into more fungible cash in parents' pockets.

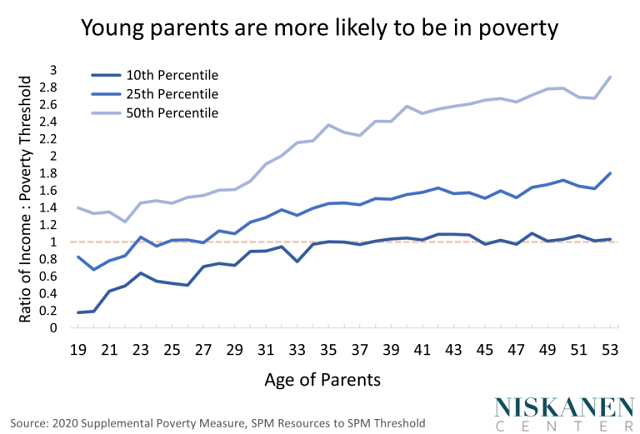

As a general rule, earlier is better when delivering assistance to families, whose financial security tends to improve as parents age, advance in their careers, and accumulate savings. Since parents will never be younger than when they have their first child, delivering assistance at the time of birth helps when they are most strapped for cash. And this same general pattern holds among families that go on to have two or more children.

The general rule that earlier is better when it comes to supporting families is especially true once the circumstances specific to pregnancy, childbirth, and its immediate aftermath are factored in. Families are often forced to do more with less, making various purchases necessary to care for an infant with a lower income because of the work disruptions associated with birth itself, particularly for the mother. The financial strains associated with childbirth not only make life harder than it ought to be for cash-strapped parents but may also impede the child’s long-term development.

Eliminating pregnancy-related health care costs not only delivers assistance to families when they need it most, but it also delivers that aid in a manner that allows them to avoid many of the most headache-inducing aspects of America’s healthcare system, such as navigating opaque prices, unforeseen medical needs, and paperwork hassle involved in dealing with billing. By alleviating these burdens, parents are freed up to focus on what matters most: their new child.

Is the Goal Family Policy or Anti-poverty Policy?

Leah and Patrick are correct in identifying that over 4 in 10 births are already free through Medicaid. If narrowly targeting funds at the absolute neediest households is the definition of what good family policy entails, they are correct in assessing that more effective policies likely do exist.

The same can be said when approaching this question solely from the standpoint of minimizing the number of terminated pregnancies in America. Medicaid does indeed already provide birth-related health care at zero direct cost to the demographic of women most likely to undergo an abortion procedure. Even so, making birth free for all Americans remains quite attractive for those looking to bolster families in a broader sense.

Working families just above Medicaid’s income eligibility threshold often face significant out-of-pocket healthcare expenses. That’s because Medicaid is delivered on an all-or-nothing basis. As a general matter, families on employer-sponsored insurance that are closer to the poverty line devote a higher share of their overall incomes towards financing health care in the form of co-pays and co-insurance as well as employee-side premium contributions. For birth specifically, out-of-pocket costs on private insurance are quite substantial, with the average total payment adding up to slightly over $3,000. Yet simply looking at the average doesn’t sufficiently convey the financial risk faced by families on private insurance during birth. About 17% will face a bill of over $5,000, and 1% may face one higher than $10,000. Saddling families with massive bills for birth-related care doesn’t magically become okay the moment a family crosses the Medicaid eligibility threshold.

The ugly flipside of Medicaid’s narrow targeting is that married couples are disproportionately unable to access the program. To illustrate, while married women account for 60% of US births, they make up only a third of pregnant women covered by Medicaid. It’s worth briefly unpacking a scenario to better understand how Medicaid’s marriage penalty limits access to free birth among married mothers. All states are required to provide Medicaid coverage to pregnant mothers in households earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), which comes out to $20,000 for a family of one and $25,000 for a family of two. Given that a full-time worker earning the federal minimum wage makes roughly $15,000 per year, a pregnant woman has a much easier time accessing the generous support that Medicaid provides for childbirth if she is not married to the child’s father. Because fathers’ incomes typically do not decline to the same extent as mothers’ during pregnancy, this further disadvantages married women from the standpoint of accessing free birth-related care.

In addition to disproportionately failing to reach pregnant married mothers, Medicaid’s penalization of marriage likely prevents some portion of unions from forming in the first place. Medicaid’s sharp cut-off is particularly nasty for Americans with meaningful medical expenses, and the birth of a child is often the costliest medical event a woman will have faced up until that point in her life. While Medicaid is invaluable as a safety-net program, its sharp benefit cliffs make expanding it further up the income ladder inappropriate from a pro-family perspective.

Make Private Insurance Family-Friendly

Aside from moving towards Medicaid for all, it is important to ensure that private insurance isn’t such a raw deal for families. To achieve this, healthcare costs that are disproportionately shouldered by parents can either be transferred from private insurers to the government or the coverage provided by these insurers can be shaped in a more pro-family direction.

Foster and Day’s “Make Birth Free” proposal is an example of the first strategy. This approach not only alleviates parents of the concentrated out-of-pocket burden of childbirth, but it also makes private health insurance more affordable by transferring to the government the share of childbirth financing that is currently embedded in the monthly premiums families pay. The appeal of this approach is that it is relatively simple to administer and easy for families to navigate.

Shaping the coverage offered by private health insurers is another strategy to insulate parents from the cost of childbirth. I’ve written previously on the various strategies that could be employed to provide first-dollar coverage for birth-related care. The most straightforward way of achieving this would involve a two-step process. The first step would involve amending the ACA marketplace regulations, exempting a comprehensive basket of pre-, peri-, and post-natal expenses from copays. The second step would be to change the law so that pregnant women can access Premium Tax Credit subsidies to purchase an ACA plan regardless of whether or not the plan provided by their employer or their spouse’s employer is deemed to be “affordable,” and allow them to sign up immediately by making pregnancy a “qualifying life event.” This approach leans heavily on the ACA marketplace because these plans are far easier to make family-friendly than those provided through employers. Indeed, a major perk of this approach to financing free birth is that it aids the transition away from the various anti-family shortcomings inherent to employer-sponsored health insurance, building upon actions taken under the Trump and Biden administrations to move health insurance in a more family-centered direction.

Regardless of how we go about it, making birth in America free should absolutely be an aspiration among those looking to advance a pro-family policy agenda. While there are multiple ways to achieve this, eliminating the out-of-pocket costs associated with birth is correct on the merits.

Our concern for families’ well-being shouldn’t be narrowly focused on those earning below a certain income. A genuinely pro-family outlook on policymaking must consider how the well-being of families with children corresponds with that of their childless peers with similar educational and professional backgrounds. Given the growing share of Americans that report not wanting to have children, it’s worth reflecting on whether we’ve structured policy in ways that make parenthood needlessly difficult, which might dissuade Americans from the prospect. We all have a stake in strong families, either directly or indirectly in terms of financing programs such as Social Security. Making birth free for all Americans would be a good first step.

Robert Orr is a policy analyst at the Niskanen Center.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.