Highlights

- At the end of their reproductive years, women in Canada have about 0.5 fewer children than they desire, on average. Post This

- The view that parenting is demanding is a bigger factor for low fertility in Canada than housing or child care costs. Post This

- In Canada, unlike many other countries, fertility rates and desires rise with income: richer Canadians want more children, intend more children, and have more children. Post This

In almost every industrialized country, fertility rates are below, and sometimes far below, the “replacement rate” of 2.1. Here in the U.S., the current fertility rate is around 1.6. In Canada, it’s even lower, at 1.4. To explore what might be driving these low rates, I recently conducted a survey with Cardus to ask 2,700 Canadian women (including an oversample of women taking the survey in French, and immigrant women taking the survey in French or English) about their family desires.

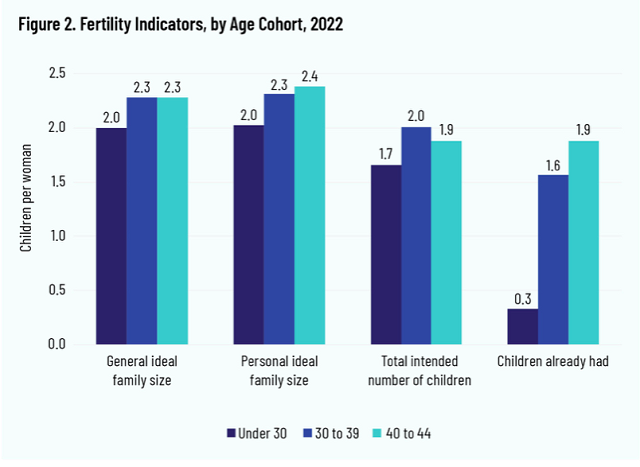

What we found was striking. Canadian women report desiring about 2.2 children, but don’t expect to achieve those desires. They expect to have about 1.9 children, a foreshortening of family desires of one child among every three women. But even that expectation is fraught: with an actual fertility rate of 1.4, Canadian women will almost certainly undershoot their desires. At the end of their reproductive years, women in Canada have about 0.5 fewer children than they desire, on average. “Missing” births vastly outnumber “excess” births. Nearly half of women at the end of their reproductive years have had fewer children than they wanted.

This under- and over-shooting has real consequences. Women who accomplish their fertility desires are happier than women who have more or fewer children than they desire. Although “excess” births have a larger unhappiness effect than “missing” births individually, Canadian women lose more aggregate life satisfaction from “missing” than from “excess” births. That’s because “missing” births are almost four times as common. In short, “missing” births are very significant social problem.

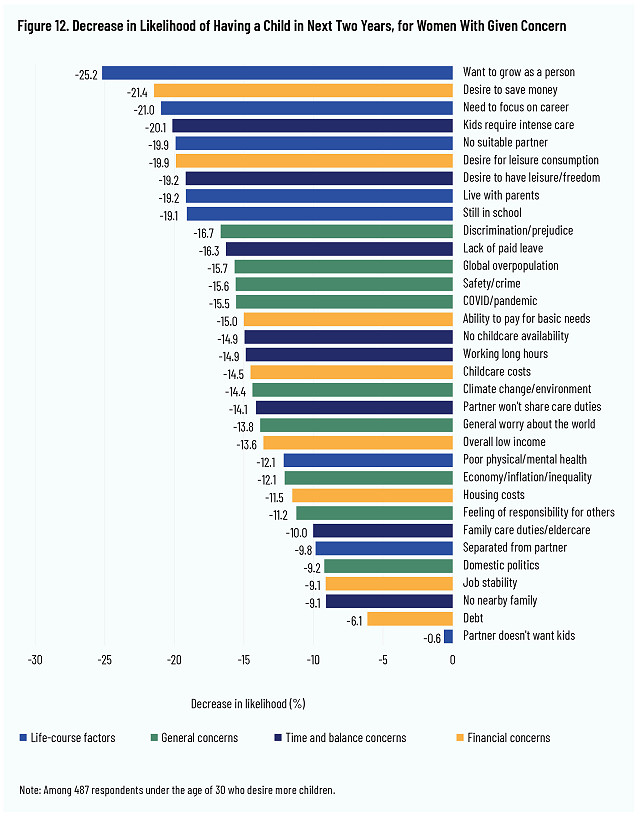

So if missing fertility desires has these consequences, why does it happen? Many factors influence Canadian women to have fewer children than they desire, but the most influential factors from our survey relate to the ideas that children are burdensome, that parenting is intensive and time-consuming, and that women want to finish self-development and exploration before having children. In fact, the view that parenting is demanding is a bigger factor for low fertility than housing or child care costs. In the report, we call these ideas “capstone kids” and “intensive parenting.” Essentially, instead of seeing childrearing as part of a process of self-development and personal growth, and as something that can be “learned on the job,” Canadian women tend to see childrearing as something to be added on after self-development is complete, and after a person has already studied up to learn to be a good parent.

This creates very striking socioeconomic divides. In Canada, unlike many other countries, fertility rates and desires rise with income: richer Canadians want more children, intend more children, and ultimately have more children. In Canada, all fertility indicators rise almost linearly with income. In the United States, by contrast, fertility has a “U-shape” with income, being highest among poor and very-rich Americans. Meanwhile, fertility preferences in the U.S. have a “hump shape,” being lowest for poor and rich Americans. Why Canada’s fertility patterns vary so much by class compared to fertility patterns in America is unclear. It may be that Canada’s skills-based immigration system blocks many family-minded, low-income people from coming to Canada, which in turn leads to lower society-wide fertility.

Read more, including detailed breakouts by socioeconomic class, racial and ethnic groups, and specific factors impacting fertility, in the full report from Cardus.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies and Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence.