Highlights

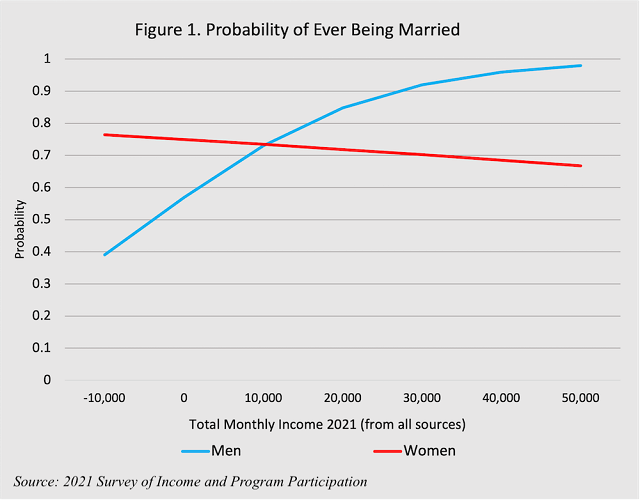

- For men, a greater personal income is associated with a greater chance of marriage; for women, a greater personal income is associated with a lower chance of marriage. Post This

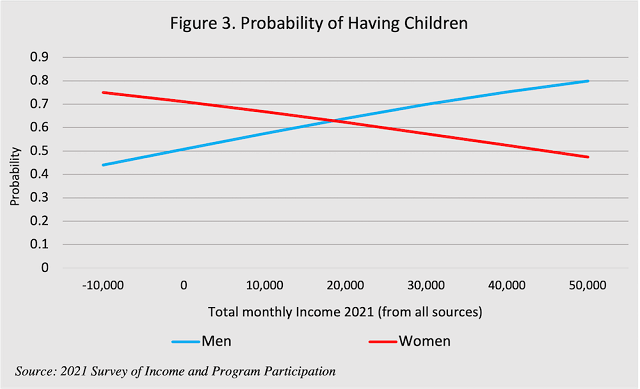

- Higher income men are more likely to have children; higher income women are less likely to have children. Post This

- Men and women in the U.S. are clearly making very different behavioral choices, on average, about who to marry, with whom to have children, and about income earning activities, especially after kids. Post This

Men and women are different. They tend to make different choices in real life, especially with regard to sexuality, marriage, and parenting. This was illustrated in an article I published in Evolution and Human Behavior in 2021, which showed that for men, a greater personal income was associated with a greater chance of marriage, a lower chance of getting divorced, a higher chance of having children, and a greater chance of remarriage after divorce. For women, a greater personal income did not increase their chance of marriage but did increase their chance of divorce, while it decreased their chance of having children and their chance of remarrying after divorce.

These results were from a representative sample of the U.S. population, the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) fielded by the Census Bureau. The analysis was cross-sectional, which means that income and family outcomes were measured at the same time point in 2014. These findings are a little old now, and I know from teaching undergraduate students that people often think that things change quickly. So, I repeated the analyses again using the 2021 SIPP. Being ever married, ever divorced (if ever married), and ever having children, the number of biological children, and being ever remarried after divorce were all measured for individuals in 2021, as was total monthly personal income.1 Total monthly personal income can be negative because it includes business profits and losses. The total number of cases was 56,725.

Figure 1 shows the probability of ever being married by total monthly personal income from all sources for men and women. Given the wide range of total monthly income on the x-axis, please note that it is well within the range given in the data. For men, a greater personal income is associated with a greater chance of marriage; for women, a greater personal income is associated with a lower chance of marriage. This sex difference is statistically significant, which means it can be assumed that this result applies to the general population of the U.S.

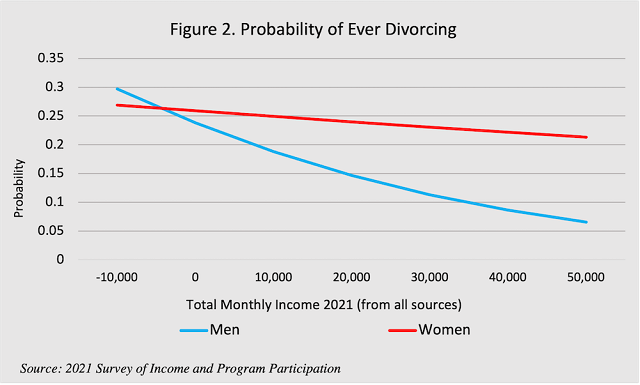

Figure 2 shows the probability of ever divorcing (if ever married) by personal income from all sources for men and women. For men, a greater personal income decreases the chance of divorce; for women, a greater personal income also decreases the chance of divorce but not nearly so much. The sex difference is statistically significant.

Figure 3 shows the probability of having biological children, by total income, for men and women. Here, the sex difference is very stark. Higher-income men are more likely to have children; higher-income women are less likely to have children, and the sex difference is statistically significant.

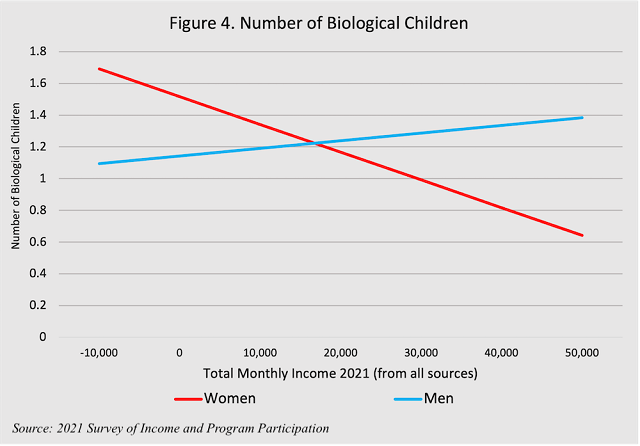

Figure 4 shows that men with higher personal incomes are more likely to have a larger number of biological children than low-income men. The reverse is true for women. As before, the sex difference is statistically significant. This is, in part, because women with more children are less likely to work outside the home than women with no or few children, and it may be that men with more children work more than men with no or few children.

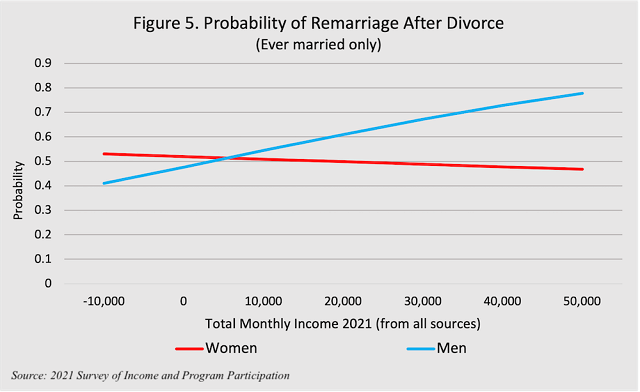

Last, Figure 5 shows the chances of remarriage after divorce. High-income men are much more likely than low-income men to remarry after divorce. High-income women are less likely than low-income women to remarry after divorce. Once again, the sex difference is statistically significant. The greater likelihood of remarriage for higher-income men is a phenomenon memorably referred to as the “recycling” of eligible men by Philip Blumstein and Pepper Schwartz in their book American Couples (1983).

These results largely replicate my earlier findings. They show that men and women in the U.S. are clearly making very different behavioral choices, on average, about whom to marry, with whom to have children, and about income-earning activities especially after having children. The results suggest that higher-income men are attractive to women as candidates for marriage and fatherhood, as a higher personal income increases men’s chances of both ever being married and ever having biological children. There is no evidence that a higher personal income increases women’s chances of marriage and motherhood; in fact, there is evidence that the reverse is true.

This continued association between personal income and family outcomes for men and women in the U.S. occurs despite the great changes in women’s roles over the past 50 years. This includes the fact that more than half of all marriages in the U.S. are now dual-earner marriages, and in about one-third of all marriages, spouses earn about the same. Most sociologists would argue that this is because we live in a gendered social world, where it remains normative for men to provide for families. Of course, this is true. But evolutionary psychologists would argue that this gendered social world is sustained, in part, by emotions and psychologies that differ somewhat by sex, particularly the powerful emotions having to do with sexuality, marriage, and parenting. Thus, even in the U.S. where women can and do earn as much as men, the actual behavioral choices men and women make differ, despite the tremendous economic and cultural changes in our society.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life (Routledge 2016), editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018) and author (with Martin Fieder and Susanne Huber) of Not So Weird After All: The Changing Relationship Between Status and Fertility (Routledge, 2024).

1. Total monthly personal income from all sources includes earnings, business income, and income from investments or government programs for men and women. I controlled for age, age-squared, race, and ethnicity, because the probability of marriage, divorce, and having children differs by these factors.