Highlights

- The majority of Spanish youth have an ambivalent attitude toward marriage. Post This

- Nearly 80% of young people in Spain prioritize hobbies/leisure and professional career over the “family oriented” priorities of marriage and parenthood. Post This

- Our findings suggest that young adults in Spain hold fractioned beliefs about marriage. Post This

Spain celebrated this summer as its Women’s National soccer team captured their first-ever World Cup title. But beyond the world of sports, the country has distinct statistical markers that haven't garnered as much global attention. For years, Spain has quietly held significant rankings in areas such as its high gross divorce rates and a notably late average age for first marriages, age 36 for men and 34 for women. These facets of Spanish society often remain underemphasized in both academic research and public discourse. Along with the decline in fertility rates and the rise in alternative relationship models, these trends may imply a departure from Spain's traditionally "familistic" social framework. These trends call for a deeper exploration into the changing social norms and beliefs about marriage, and how these shifts are reshaping behaviors and life choices in Spain.

What beliefs do Spanish young adults hold about marriage? What are their relative life priorities? And to what effect are their beliefs associated with risk-taking behaviors? In our recently published study, Cecilia Serrano and Javier García-Manglano shed light on these questions. Our findings suggest that young adults in Spain hold fractioned beliefs about marriage and can be classified beyond a negative/positive dichotomy. Furthermore, classified beliefs about marriage map to a corresponding pattern of life priorities, relationship decisions, living arrangements, and behaviors.

Building on past research, we systematically classify self-expressed beliefs about marriage under the framework of the Marriage Paradigm Theory. This theory proposes that all individuals, married or not, form a set of attitudes and expectations surrounding marriage. These beliefs and attitudes are conceptually divided into two categories: beliefs about getting married, and beliefs about being married.

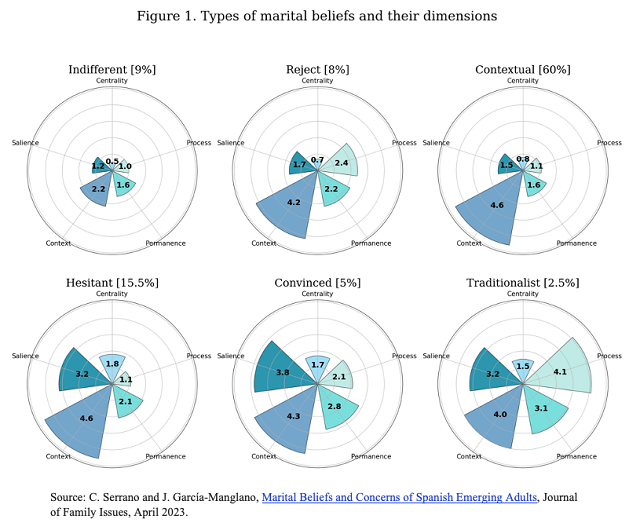

Surveying a representative sample of Spanish emerging youth (18-30 years old) we asked participants to report on particular opinions and attitudes reflecting marital salience (getting married is a very important goal), timing (there’s an ideal age to get married), context (money and finances are a major barrier to getting married), processes (in an ideal marriage, the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home), permanence (marriage is for life, even if the couple is unhappy) and centrality (how much importance do you expect to place on marriage?). Together, these variables were used to classify the population of participants into distinct classes based on a shared paradigm.

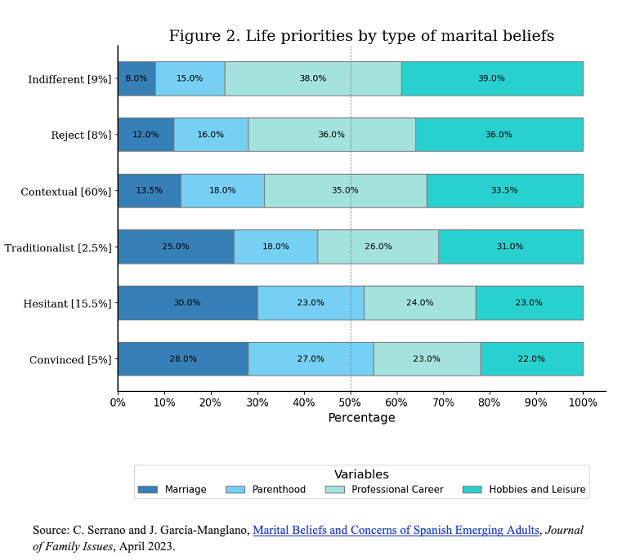

Furthermore, participants assigned relative weights to “ultimate concerns” broken down into: marriage, parenthood, professional career, and hobbies/leisure. They were asked to prioritize by assigning a percentage to each life dimension, adding up to a combined total of 100. The study later mapped the relationship between beliefs held and the priority assigned to these ultimate concerns.

Lastly, using the participants’ responses regarding risky behaviors such as binge drinking, drug consumption, or early sexual activity, this study explores what associations exist between the held marital beliefs and risky behaviors. Marriage beliefs’ ability (or lack thereof) to shape behaviors can imply the normative role marriage holds in society.

Marital paradigms in the Spanish population

While earlier research suggests at least three marital paradigms among United States’ emerging adults, we discover a more divided distribution and a primarily negative or indifferent attitude towards marriage among Spain’s emerging adults. Nearly 60% of the population holds a shared marriage paradigm; however, in the Spanish case, the remaining 40% splinter into 5 additional paradigms.

The following chart displays the uncovered distribution based on marital beliefs:

The Hesitant, Convinced, and Traditionalist groups display favorable views of marriage represented by higher centrality and salience. They make up 25% of the population, yet one can observe clear differences. For example, Traditionalists give high importance to marriage and consider it among their priorities; however, with over 88% of the group being single and 83% being male, one must question if they have difficulties finding partners who share their more “traditional” views of marriage in terms of gender roles and permanence. Meanwhile, both the Hesitant and Convinced groups had the highest percentages of committed relationships; however, the extremely high importance placed on the economic context in the Hesitant group may explain the lower percentages of the engaged and married as compared to the convinced group.

Notably, the overall distribution is highly concentrated in what is defined as the Contextual group, in which participants identify strongly with statements such as money being an important obstacle for marriage, the importance of having saved a sufficient amount before marriage, their economic circumstances being a primary factor to consider, or that they should be able to pay for their wedding before getting married.

While this may seem to uphold a common storyline pointing to Spain’s economic conditions as the culprit for delayed marriages, the low centrality and salience displayed by the Contextual, Reject, and Indifferent groups seem to indicate that marriage is not a priority for more than 75% of Spanish young adults. This is intriguing given that, in 2019, Spain was the second highest average spender on weddings in the world, trailing only the United States. When looked at as a percentage of annual wages, the data becomes even more startling. The average spending on weddings in Spain in 2019 represented 78% of average annual wages versus 45% in the United States. This seems to suggest that weddings in Spain are treated as a somewhat “luxury good” and could partly explain the high emphasis placed on context.

While the economic investment in weddings is notably high in Spain, indicating a significant value placed on the event itself, the underlying beliefs and motivations surrounding marriage need to be better understood. Diving deeper into this aspect, our research offers further contributions to our understanding of marital beliefs, specifically defining the association between marital beliefs and life priorities.

Priorities by marital paradigms

As we can see in Figure 2 below, nearly 80% prioritize hobbies/leisure and professional career over the “family oriented” priorities of marriage and parenthood. Indeed, consumer behavior in young adults reflected these patterns this summer where spending exceeded inflation in “leisure” categories: clothes and shoes (10.2%), restaurants (10%), hotels (9%), or airline tickets or car rentals (28.7%).

Only the Hesitant and Convinced groups display stronger “family priorities,” being the only two groups that exceed 50% of the weight destined to marriage and parenthood concerns. Yet, one major difference between the Hesitant and Convinced groups is their living arrangement. In both groups, 35% were living with their partner; however, the percentage of participants living alone instead of with their parents in the Convinced group was four times higher than in the Hesitant group. Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, conclusions cannot be drawn on the causality of this relationship, but it is an interesting correlation.

Implications

Despite the differences between paradigms in terms of beliefs and priorities, the effect on other behaviors for Spanish young adults were not as relevant as in other contexts. Previous research has shown that in the United States, anticipating marriage in the near future is linked to lower rates of substance use or less permissive sexual values. Other researchers have found that young adults with stronger desires to marry are less likely to engage in risky behaviors such as binge drinking, drug consumption, or early sexual activity. In the Spanish context, some behavioral differences emerged. For instance, while 20.5% of the Reject group has had an unprotected sexual relationship with someone other than their partner, only 6% of the Convinced group has. There were some differences in porn use, with the Reject group reporting higher use than the other groups, but only for men. However, the dissimilarities between groups in sexual and risky behaviors were not very significant.

This contrast between the United States and Spain suggests that marriage in the Spanish context has lost its normative role. The majority of Spanish youth have an ambivalent attitude toward marriage, while American youth still hold somewhat favorable views towards marriage.

This research paints a rich tapestry of marriage views, priorities, and behaviors among Spanish youth. While economic factors undoubtedly play a role, a deeper cultural narrative is unfolding. Recognizing these complexities is pivotal for anyone keen on understanding the intricate dynamics shaping family decisions in contemporary Spain.

The authors are members of the Youth in Transition research group, Institute for Culture and Society, at the University of Navarra, Spain.