Highlights

- More than one-quarter of men and women in prison had a minor child at home at the time of their arrest. Post This

- Children who grow up in families in which a parent has been imprisoned are more likely to experience learning, behavioral, and emotional difficulties. Post This

- There is a strong association between the type of family in which a child grows up and the likelihood that the child will have a parent or sibling serve time in prison. Post This

Much attention has been paid to the criminal justice system in the United States and the need for reform. Yet there is a dearth of information about the well-being of children of incarcerated men and women.

We know from periodic surveys of prisoners conducted by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics that family dysfunction is a recurring theme in the life stories of convicted criminals.1 Most men and women in federal and state prisons did not grow up in stable two-parent households. They came from single-parent families, were raised by grandmothers or aunts, or spent years in foster homes and institutions. More than half have a father, brother, or other family member who has also “done time.” And more than one-quarter had a minor child at home at the time of their arrest.2

How do the children who are left at home when fathers or mothers are imprisoned function and develop? Do they show resilience in the face of separation from a cherished parent? Or do they have more than their share of learning, emotional, and behavioral problems? I analyzed data from a national survey of children’s health to get some preliminary answers to these questions.3

4 Million U.S. Children Have Had a Family Member Imprisoned

As of 2023, there were some 4 million children under the age of 18 in the United States who had a parent, sibling, or other family member imprisoned. These youngsters represent 5.8% of the U.S. population under 18. The true figure may be considerably higher, according to a 2022 study4 that made use of longitudinal links between survey and administrative data from 13 U.S. states. It found that 8.8% of children are exposed to a parent or other potential caregiver in prison by age 18.

There is a strong association between the type of family in which a child grows up and the likelihood that the child will have a parent or sibling serve time in prison. As may be seen in the figure below, among children who live with their mothers only, 1 in 8 (13%) has had a parent or sibling imprisoned. The same is true of about 1 in 7 who live with a birth parent and stepparent (15%) and 1 in 3 (33%) who live with a grandparent rather than either birth parent. By contrast, only 1% of children living with both a father and mother have experienced parental or sibling imprisonment.

After controlling for parent education, family poverty, immigrant status, and the child’s age, sex, and race and ethnicity, the odds of parental imprisonment are 9.5 times higher for children living with mothers only, 10 times higher for those living with a birth parent and stepparent, and 28 times higher for those living with grandparents, compared to children with fathers and mothers present in the home.

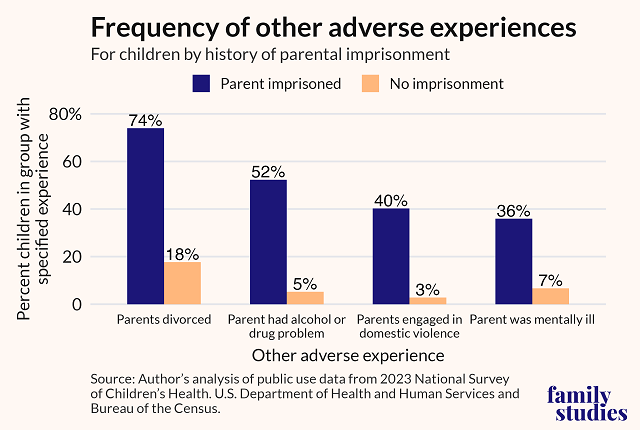

Parental Imprisonment Is Linked to Other Adverse Experiences

Children who grow up in families in which a parent has been imprisoned are exposed to other troubling experiences. Nearly three-quarters have seen parents get divorced. More than half have lived with a parent with drug or alcohol addiction, and 40% have witnessed adult family members slapping, hitting, kicking, or punching one another. More than a third have lived with a parent or other family member who is mentally ill. Each of these stressful conditions is far more common among youngsters with a history of parental imprisonment.

Developmental Difficulties More Common for Kids With Incarcerated Parents

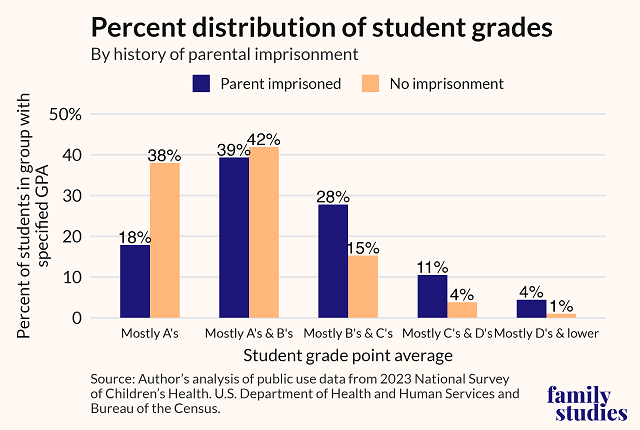

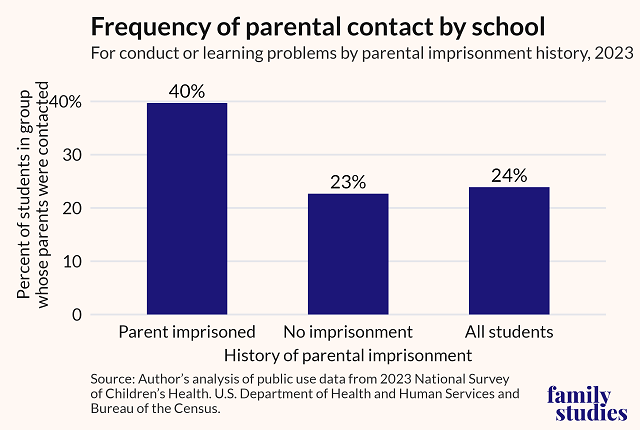

Children who grow up in families in which a parent has been imprisoned are more likely to experience learning, behavioral, and emotional difficulties. They get lower grades in school. Their parents or guardians are contacted more often by teachers because of the student’s misbehavior or academic struggles. They act in ways that lead counselors to describe them as anxious or depressed, or as having attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD).

Lower Grades. Students who had a parent imprisoned are half as likely to get “A” grades in school as students who have not had a parent incarcerated: 18% versus 38%. They are three times more likely to get mostly “C’s,” “D’s,” or lower grades: 15% versus 5%.

After controlling for family disruption, parent education, family poverty, immigrant status, and child’s age, sex, and race and ethnicity, the odds of getting mostly A grades are 64% lower for students with incarcerated parents than for those with no history of parental imprisonment.

In addition, students from intact families have 1.80 times higher odds of getting A grades than students from disrupted families. And female students have 1.56 times higher odds of getting “A’s” as male students.

School Misbehavior. Compared to students who have not experienced parental incarceration, nearly twice as many American students with histories of parental imprisonment get notes sent home from school because of their misconduct in class or learning difficulties.

After controlling for family background factors and child characteristics, children of prisoners have 1.81 times higher odds as other students of getting notes sent home from school. Students from disrupted families have 1.63 times higher odds of disciplinary contacts as those from intact families. And boys have 1.50 times higher odds than girls do.

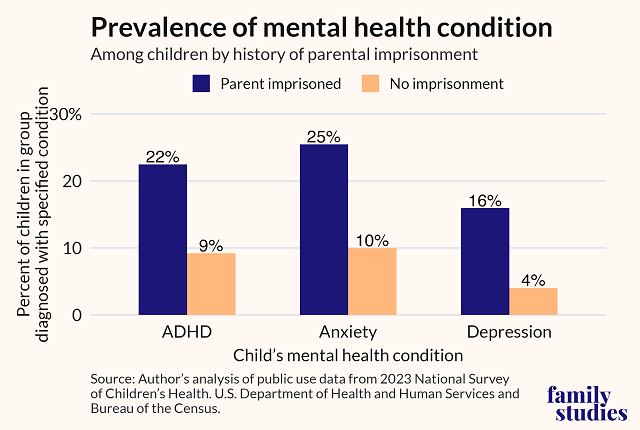

Depression, Anxiety, and Attention Deficit. Children with a parent who has been incarcerated are more likely to be diagnosed with mental health conditions than are children with no history of parental incarceration.

After controlling for family disruption and other family background factors and child characteristics, children with parental incarceration continue to have higher odds of receiving mental health diagnoses than do children without parental imprisonment. Specifically:

- They have 2.42 times higher odds of depression.

- They have 2.06 times higher odds of anxiety.

- They have 1.74 times higher odds of ADHD.

Why Children of Prisoners Have More Problems

This analysis of national survey data shows that children of prisoners have significantly more learning, emotional, and behavioral problems than children who have not experienced parental incarceration. And these differences persist even after controlling for the lower education and income levels of prisoners’ families and disparities in the racial, ethnic, and immigrant composition of the two groups.

Many would-be reformers of the criminal justice system would attribute the increase in child disorders to the family turmoil caused by imprisonment of a parent: the shame of having a parent convicted of a crime; the stress of separation from that parent; and the strain of living with an overwhelmed single parent in reduced financial circumstances. Parental imprisonment is correlated with parental divorce and, not infrequently, the loss of regular contact with not just one but both parents. There is no question that family disruption is correlated with incarceration and contributes to children’s problems. Yet imprisonment remains a significant predictor of developmental disorders even when family disruption is considered.

This analysis also shows that families of prisoners have signs of dysfunction apart from those related to the criminal justice system, such as alcohol or drug abuse, mental illness, and domestic violence. Abigail Marsh found that some criminals lack remorse and empathy for the feelings of people who may be hurt by their actions.5 They adhere to beliefs, attitudes, and rationalizations that blame others for negative behavior as a way of justifying their own criminal actions.6 This can negatively affect their interactions with their children.

It is vital to learn more about the genesis of delinquency and emotional disturbance in children whose parents are caught up in the criminal justice system, so that we can do a better job of supporting these children through family trauma and in short-circuiting the transmission of anti-social conduct and future incarceration that often comes with it.

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce.

1. Survey of Prison Inmates Data Analysis Tool (SPI DAT).

2. Author’s analysis of data from 2016 survey of prison inmates. See also: Laura M. Maruschak, Jennifer Bronson, and Mariel Alper. Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children. Bureau of Justice Statistics. March 2021.

3. The survey was the 2023 National Survey of Children’s Health. Public use data file downloaded from U.S. Bureau of the Census.

4. Keith Finlay, Michael Mueller-Smith, & Brittany Street. Measuring Intergenerational Exposure to the U.S. Justice System: Evidence from Longitudinal Links Between Survey and Administrative Data. June 9, 2022. University of Michigan.

5. Abigail Marsh. The Fear Factor: How One Emotion Connects Altruists, Psychopaths, and Everyone In-Between (NY: Basic Books, 2017).

6. Glenn D. Walters. Closing the Integration Gap in Criminology: The Case for Criminal Thinking (New York: Routledge, 2021).