Highlights

- “I believe that it has to do with the brutality of the dating market, and the difficulty so many women have finding marriageable partners,” Michelle Goldberg said at the NMP event. Post This

- “It’s the most grounding experience I’ve ever had,” said 23-year-old media influencer Brett Cooper about getting married last year. Post This

- "The best predictor of whether or not you are above replacement birth rates, if you’re an American, is how religious you are and how conservative you are,” said Louise Perry. Post This

Media influencer Brett Cooper did something last year that most people her age won’t: she got married. “It’s the most grounding experience I’ve ever had,” she told a crowd gathered at the University of Virginia for the National Marriage Project’s spring conference, cosponsored with the Wheatley Institute. Cooper is 23 and had celebrated her one-year anniversary the week before the event. The conference topic was: “In Pursuit: What do marriage and motherhood have to do with the happiness of women?”

Data show the majority of Cooper’s peers don’t necessarily think there’s a connection. The median age at first marriage for American women is now 28.6. What’s more: a record share of young women, about one-third, are projected to never marry. Cooper told the crowd at UVA she thinks women are hesitant to marry young because of years of conventional “wisdom” cautioning them against sacrificing their education, career and personal freedom for what our culture suggests is essentially a losing proposition for women.

Cooper’s experience is not unlike that of a woman Brad interviewed for his book, Get Married. A recent UVA grad, Holly said her fellow college students were “more focused on their education and getting their career started” than marriage. Settling down with someone, Holly said, is riskier when a woman doesn’t have an already established “career and success to fall back on.”

This is what we call “the Midas Mindset.” It’s the idea that money, educational attainment and, especially, a stimulating career offer the deepest sources of personal fulfillment and therefore should be the highest goal for men and women.

The Midas Mindset has proved captivating, but the data don’t support it. Married American women report higher rates of happiness than unmarried women, according to the most recent General Social Survey. And the happiest women in America are married mothers.

Married moms also report lower rates of depression, and higher rates of personal meaning and satisfaction (despite also reporting higher stress levels), according to family scholars Wendy Wang and Yifeng Wan, who presented their recent findings before the National Marriage Project’s evening panel last week.

In other words, research data continues to poke holes in the Midas Mindset. So why do so many young women still find it so convincing?

Why are young women reluctant to marry?

New York Times opinion columnist Michelle Goldberg argued at the evening panel that women aren’t eschewing marriage because they’ve “watched too much ‘Sex in the City’ and (have) been told that they should put their career first.” Rather, she said, women say they simply can’t find any men worth marrying.

“Inasmuch as there has been less of a norm around marriage, I believe that it has to do with the brutality of the dating market, and the difficulty so many women have finding marriageable partners,” she said.

Goldberg suggested the Midas Mindset has a kernel of truth. “Where marriage seems to have really fallen apart as a social norm are in [socioeconomic] classes where it’s often a bad economic bargain for women,” she said, noting that marriage rates are higher among the upper classes.

British journalist Louise Perry agreed the mismatch in earnings and educational attainment between men and women has contributed to a dysfunctional dating market, often skewed against men. Perry referenced the work of Institute for Family Studies researcher Lyman Stone and suggested young men are “struggling to signal their appropriateness as husbands and fathers in the way that they might once have been able to — by, for instance, having a good job, owning a house, having military service.”

At the same time, as men are finding these “signals of suitability” less attainable, Perry said, women are excelling professionally beyond prior generations. Michel Martin, host of NPR’s Morning Edition, said the African American community — among whom only about 30% of adults are married — has grappled with these issues for years.

“It’s not because marriage doesn’t confer economic benefit,” Martin said. “A lot of African American men don’t see a way to be the kind of man they want to be in marriage, and I think they avoid it for that reason … they don’t see a way to fulfill the role of a husband and father” that includes being a good provider.

But the data suggest there’s more going on here than economics. Culture also shapes who is getting married and starting a family today. Specifically, there is one group of American women for whom both marriage and fertility rates remain relatively high and stable, regardless of income: religious Americans.

That suggests there are cultural and philosophical concerns also weighing on American women’s views of marriage and motherhood. Three of the four panelists — all but the newly married Brett Cooper — are married moms, and each of them shared frankly about the joys and exhaustions of family life. But they agreed that motherhood, while frequently straining and stressful, was an unparalleled source of personal meaning and satisfaction.

“Parenting is all joy and no fun,” Martin said. “You give up something in the short term for the larger purpose and the mission, and the larger joy … but it requires tremendous sacrifice in the short run.”

How religiosity predicts fertility

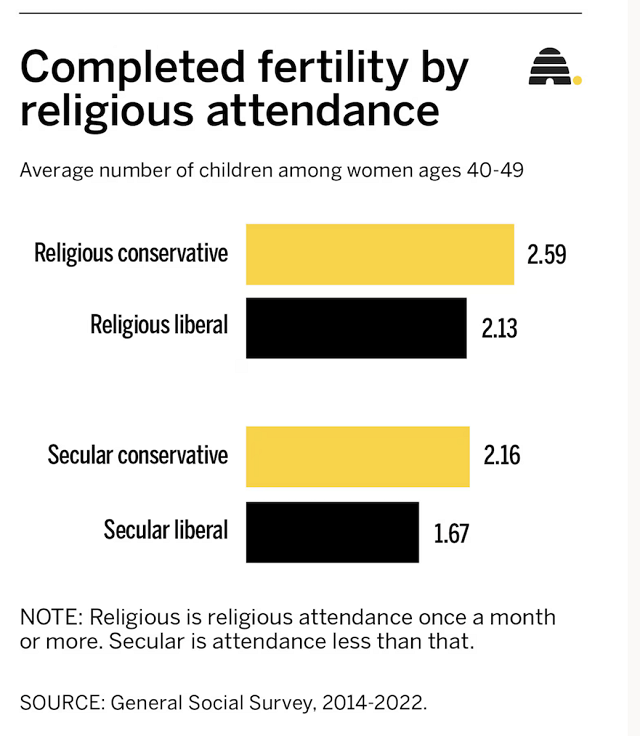

Louise Perry agreed that motherhood requires a commitment to delayed gratification and self-sacrifice. That may explain why religious conservative women — who generally place higher value on those virtues — are having more children. “I mean the best predictor of whether or not you are above replacement birth rates, if you’re an American, is how religious you are and how conservative you are,” she said.

Clearly, Perry is onto something. Our analysis of the General Social Survey (2014-2022) indicates that the completed fertility — the number of children a woman has throughout her lifetime — of religiously conservative women in their forties is 2.59, higher than the fertility of secular liberal women, which is just 1.67. This distribution tells us that the view that marriage and family trends in America are primarily a reflection of class differences — a view that Goldberg articulated at the UVA event — misses major cultural dynamics also playing out in American life. In simple terms, it’s not just class that determines how and whether women are starting families in America today. It’s also culture.

After the panel discussion, the audience at UVA — mostly students — took turns asking the panelists questions. Most were practical, but suggested the students are open, if timid, about the prospect of marriage and family: Can domestic duties truly be shared “equally” between moms and dads? Where can someone looking for a relationship actually meet someone?

Michel Martin pointed students to the song “My Best Guess” by indie pop artist Lucy Dacus. Marriage may or may not work out, Martin said, but students should go for it anyway, “hoping for the best.” The lyrics are:

You are my best guess at the future

If I were a gambling man, and I am

You’d be my best bet

If this doesn’t work out

I would lose my mind

And after a while

I will be fine

But I don’t wanna be fine

The song rather poignantly seems to confirm the fears of Holly, the young woman Brad interviewed for “Get Married.” Holly worried marriage was too “risky” to prioritize over her career — ostensibly because it might not “work out.”

But the data ultimately suggest that despite the risks of heartbreak and struggle — risks inherent to all of life — the riskier bet for women who desire meaning and fulfillment is to avoid marriage and motherhood. After all, today most marriages go the distance, and most women are happily married. These women may be better served listening to a different song. “Loving a Person” by Christian songwriter Sara Groves paints a picture of marriage not as a commitment to stay together as long as it feels good or easy, but as a commitment to the beauty of commitment itself:

Loving a person just the way they are, it’s no small thing

It takes some time to see things through

Sometimes things change, sometimes we’re waiting

We need grace either way

Hold on to me

I’ll hold on to you

Let’s find out the beauty of seeing this through.

You can watch the full panel discussion here.

Maria Baer is a journalist and co-host of the “Breakpoint This Week” podcast with The Colson Center for Christian Worldview. Brad Wilcox is Distinguished University Professor and Director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and senior nonresident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Editor's Note: This article appeared first at Deseret News. It is reprinted here with permission.