Highlights

In recent years, Stanford economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues have pioneered the study of economic mobility in American life. His work indicates that certain types of communities are significantly more likely to foster rags-to-riches mobility for poor children over the course of their lives than other communities. In short, his work suggests that communities with less racial/economic segregation, better schools, more income equality, more social capital, and more two-parent families are more likely to promote the American Dream for poor children. So, for instance, Salt Lake City is more conducive to mobility than Atlanta.

Chetty recently presented his work at the American Enterprise Institute, where University of Maryland economist Melissa Kearney was one of several panelists to reflect on the significance of his research. Because her remarks at the AEI event are particularly noteworthy, we are providing an edited transcript of those comments here.

[T]his work by Raj Chetty and his team is truly astounding and groundbreaking. The findings are incredibly important and have just yielded such insight that we couldn’t possibly have obtained without…Raj and his team’s access and careful work with this data.

But as an economist, when you look at what they’ve put out, it’s extremely challenging from the perspective of economic analysis in economic policy. There are three key reasons why I say that.

The first is that this is sort of irrefutable data, showing us that there are real differences across places in prospects for upward mobility. But we’re left with the question of why. And the “mover” studies are even more challenging because, in two of the studies, Raj and his coauthor show us that kids who move to different places have better outcomes. So now we know that places themselves have causal impacts on kids’ outcomes.

But, again, we don’t really know why. The correlates are important, but it’s really important for us to realize, as researchers and policy observers, that the correlates are just clues as to what might be going on and where we should look. But as Raj pointed out, those are not necessarily where the solutions lie. So, we really need to keep pushing to figure out the mechanisms.

The second challenge that I take from this body of work is—what do we do with this information? The answer can’t be, in my mind, just to get everyone to move. And this is one of those things academic economists and urban economists will frequently say. If you ask, “What should we tell the mayor of a declining city?” a typical academic economist’s response (public finance economist, urban economist) is [to] give the people who live there vouchers and tell them to move. That might work in our utility maximizing model, but this is why people don’t like talking to us, right, because what mayor is going to say, “Here, everyone in Detroit, take your voucher and go to the promised land”?

Another reason I’m worried about the moving idea is because…if we think about what Raj showed us: social capital is built when people invest in their communities. And so, if we come in and say, “Hey, folks who are looking for better opportunities, you should leave,” that explicitly undermines social capital. So, I worry about that as our policy prescription as well.

Finally, on this point, I’ll make the obvious observation that it seems that a lot of what is a place is the people who live there. If we take everyone from Atlanta and move them to Salt Lake City, it’s no longer Salt Lake City. And so, at best, giving people vouchers or opportunities to move to better cities or better places is a partial solution to the problem, and we really need to figure out how to achieve better outcomes in a broader swath of the country.

Nine out of 10 poverty scholar economists that I talked to didn’t like that book [Hillbilly Elegy]. Why? Because it tells you the story is about family, this is about culture, and this is about things that we don’t understand or really know how to change.

And, finally, the thing that really makes economists squirm when we look at these results—if we’re honest with ourselves—is that the factors that seem to be correlated—again, these are the clues as to what we might need to be pushing on—they are really more about culture than are policy levers. And this keeps coming up.

We saw this last year in the bestselling book Hillbilly Elegy, and I’ll be honest: nine out of 10 poverty scholar economists that I talked to didn’t like that book. Why? Because it tells you the story is about family, this is about culture, and this is about things that we don’t understand or really know how to change.

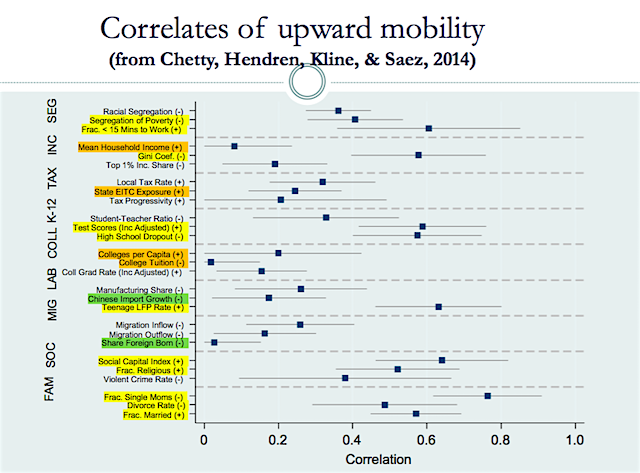

This figure below is from Raj’s early paper with this coauthors in 2014. And I want to pull this up because this is really the figure that sort of took my breath away three years ago. I think it’s important to see the factors that are highly correlated with rates of upward mobility, as well as the ones that aren’t.

If you look at the factors in yellow, these are the things that are highly correlated with rates of upward mobility. We’ve got the way our communities and our cities are organized. Residential segregation, that really matters. Social capital index, fraction religious, the fraction of households headed by single moms, and married and divorce rates. The middle one—tests and high school dropout [rates]—I think of those more as sort of behaviors that respond to the conditions.

The things that are policy levers that, as public finance economists, we might have wanted to pull to make things better, those come in really low on this chart. [Things like] state EITC exposure, tax progress, CVT, college per capita, and college tuition. The data is suggesting that those are not the clues for the things that really matter. And just for fun, I’ll point out in green that this is not about Chinese imports or a share of foreign-born. Those are not highly correlated.

So, I think this is really challenging. And it suggests culture matters. And, again, as an economist, I can’t even write “culture” without putting in quotes because we don’t know what it really is. But I think one way, as social scientists, we can think about it is this doesn’t just fall from the sky. It’s in part a reaction—a response of individuals—to their world around them and the economic conditions and opportunities that they’re seeing. So, their economic experience, their childhood experiences shape their behaviors—their decision to stay in school, to get married, or to have a birth outside of marriage. And then these things affect their rates or their likelihood of upward mobility or being in a stable or unstable relationship. And so, we’ve got this cycle of behaviors responding to conditions reflecting behaviors, and that’s what we need to figure out how to address.

I’ve become really interested in this idea of the culture of despair, which fits with what we’re seeing in sociology, ethnography, and development psychology. I think it’s something that, as economists and policy observers and policymakers, we have to think more seriously about. And this is consistent with Chetty, Hendren, and Katz' findings about MTO: the kids who move when they’re younger get the biggest effect. And that suggests that it’s consistent with the idea that somehow, we’re changing who they see themselves as, who they’re interacting with, and their worldview.

So, I think the question that this really poses for us is: How do we improve the life chances and perceptions of low-income individuals and kids, without simply moving them to live with more high-income people? Let me just list the four buckets that I would like us to hopefully talk about.

- We need to address residential segregation, and to do that seriously, will be really hard and will require much larger disruptive policy interventions than I think we’ve considered previously.

- We need to address the outlook and attitudes of these low-income kids growing up in disadvantaged areas. I think there are a lot of low-cost ways to do that, which don’t require federal legislation or even a lot of federal money. There are things that local groups, private-sector groups could do, so that’s encouraging.

- We need to leverage higher education as an engine of upward mobility. I love this latest paper that Raj Chetty and his coauthors have put out, and for me, the message that screams from that data is we need much more investment in our public universities. If legislatures and big donors want to get bang for their buck, that’s where they should be putting the money.

- And sort of underlying all of this, we need a real, dedicated investment in human potential, and that’s going to require a very well-funded, well-structured social safety net.

Melissa S. Kearney is a Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Maryland. She is also a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); a non-resident Senior Fellow at Brookings; a scholar affiliate and member of the board of the Notre Dame Wilson-Sheehan Lab for Economic Opportunities (LEO); and a scholar affiliate of the MIT Abdul Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), and co-chair of the J-PAL cities and states initiative.