Highlights

Editor's Note: The following research brief originally appeared in July 2016.

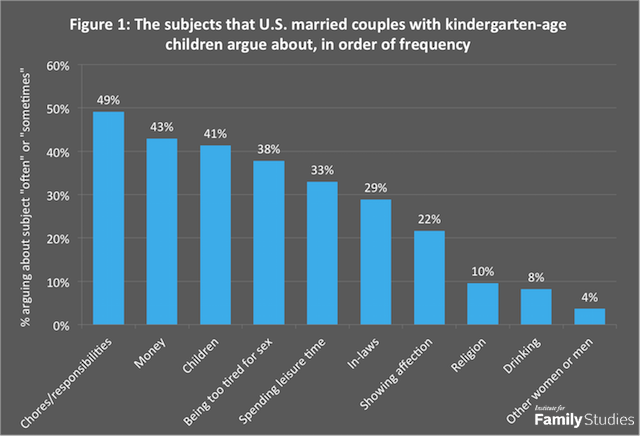

About what are married couples with children most likely to argue? No, it isn’t money, nor being too tired for sex, nor caring for the kids, although all of these are frequent subjects of marital disagreement. The most common area of contention is chores and responsibilities. Nearly half of couples with kindergarten-aged children (49 percent) said they argued about chores and responsibilities “often” or “sometimes.”

By comparison, as Figure 1 shows, 43 percent had arguments about money, 41 percent about the children, and 38 percent about being too tired for sex.

These figures are from a new analysis of survey data collected in the ECLS-K, a nationwide longitudinal study of more than 19,000 kindergarten students and their families, conducted by the U.S. Department of Education beginning in 1998. Over 11,000 of the students were living with their married birth parents when the questions about arguments were put to parents in 1999.

Couples who argued about chores were less likely to be happy with the quality of their conjugal relationships. When they “often” had such arguments, only 47 percent described their overall relationship as “very happy” (as opposed to “fairly...” or “not too happy”). Of those who argued about chores “sometimes,” 71 percent had a very happy relationship, whereas among those who had such arguments “hardly ever” or “never,” 83 percent were very happy. Couples who were less happy with their relationships and reported more disagreements were more likely to have separated or divorced by the time their children reached the eighth grade. And their children were more likely to exhibit emotional or behavioral problems at home and in school.1

Fathers Pitch In, But Mothers Want More

The primary reason for arguments about chores is the clash between the traditional division of labor along gender lines (male breadwinner, female homemaker) and the modern reality that most mothers with young children work for pay outside the home, sometimes earning more than their male partners do. In the national sample of kindergartners, 68% of the students living with married birth parents had mothers who were in the paid labor force, with 37% having both parents working full-time. By contrast, 31% had fathers who worked full-time and mothers who were full-time homemakers.

Yet as women have assumed more of the breadwinner role, men have been slower to take on a larger share of homemaker duties. With the growth of feminism, women have become more forthright in demanding that their partners share in the housework burden, and men have become more accepting of an egalitarian division of labor, at least in theory. But gaps between principle and practice continue to be a source of marital tension. So do differences in standards about such matters as how thoroughly and quickly tidying up must be done.

As women have assumed more of the breadwinner role, men have been slower to take on a larger share of homemaker duties.

There is good evidence that today’s fathers are doing more housework and child care than their own fathers did.2 For example, a study by Frank Stafford and his colleagues at the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan found that that the amount of housework done by married men doubled between 1976 and 2005, while the amount done by married women decreased over the same period.3 By the same token, the 2013 American Time Use Survey and other studies by the Bureau of Labor Statistics have found that employed married women still spend almost twice as much time on housework and child care (2.6 hours a day) as their husbands do (1.4 hours per day).4

Somewhat Fewer Disagreements In Breadwinner-Homemaker Families

It stands to reason that arguments about household responsibilities would be more common when both parents work full-time. And this is indeed the case. In the survey of kindergarten parents, 53% of families in which both father and mother worked full-time reported arguing about chores, compared with 44% of families where the father worked full-time and the mother was a full-time homemaker. When the mother worked part-time, the situation of 23% of kindergarten students, 48% of couples argued about household responsibilities. In the 4% of families where the mother was the one working full-time, however, and the father worked part-time or not at all, arguing about chores was at least as common as when both parents worked full-time: 55%. This suggests that even when fathers are at home more than their wives are, and (presumably) earn less, they do not necessarily assume the role of primary homemaker.

Even when fathers are at home more than their wives are, they do not necessarily assume the role of primary homemaker.

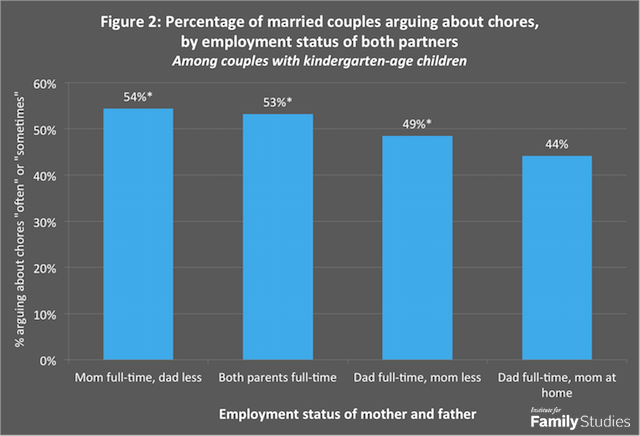

Significant differences by parental employment status remained after adjusting the frequency of arguing about chores for differences across groups in average household income, parent education, and racial composition. As Figure 2 indicates, couples where both parents worked full-time continued to have more arguments than those where the father worked full-time and the mother was a full-time homemaker (53% versus 44%). Couples in which the mother worked part-time also had more frequent arguments (49%) than the traditional breadwinner-homemaker families, as did families where the mother worked full-time and the father worked less or not at all (54%). But the apparent differences among the three groups in which the mother was employed outside the home were not statistically significant after racial/ethnic and socioeconomic controls.

*Significantly different from “Dad full-time, mom at home,” p < .05. Results control for average household income, parental education, and race/ethnicity.

More Breadwinner-Homemaker Couples Have Very Happy Marriages

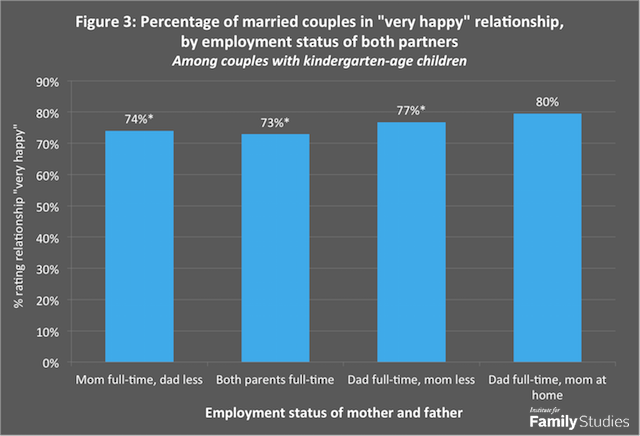

A majority of couples in all the above employment situations said their marriages were happy. However, the majorities were slightly larger when the dad worked full-time and the mom was a full-time homemaker (79% “very happy”) or worked only part-time (77% very happy), than when both parents worked full-time (73% very happy). Also less happy were couples in the relatively rare situation of the mom working full-time and the dad working part-time or not at all (72% very happy). When controlling for average household income, parent education, and racial composition, couples following the traditional male breadwinner-female homemaker pattern continued to have the largest “very happy” majority, but the other labor-force combinations were not significantly different from one another. (See Figure 3.)

*Significantly different from “Dad full-time, mom at home,” p < .05. Results control for average household income, parental education, and race/ethnicity.

Do Dual-Earner Families Argue Less About Money?

One might suppose that, even though couples where both partners are employed full-time may be more likely to argue about chores, they would be less likely to argue about money than couples where the mother is a full-time homemaker. This would be because having two wage earners provides higher family income and more economic security. The reality is that couples in which both partners worked full-time were more likely to have arguments about money: 45% versus 39%.

One could argue that the causality was in the reverse direction; i.e., couples dissatisfied with their financial situation felt compelled to have both parents in the paid labor force full-time, whereas couples who were financially comfortable could afford to have mother stay home with the children. However, the higher frequency of arguments about money persisted after controlling for disparities in household income (as well as parent education and ethnic composition): after adjustment, 46% of the dual-earner families argued about money often or sometimes, versus 39% of the breadwinner-homemaker couples.

Balancing Work and Family

For couples with young children, balancing work and family life is a challenge for families in all but the most affluent financial circumstances. The fact that nearly half of all couples with kindergarten-age children argue about chores and responsibilities shows that traditional gender behavior patterns are resistant to change and new egalitarian norms have yet to be universally accepted. It appears to be easier for couples with young children to achieve a harmonious balance when they follow the traditional pattern of having the father be the principal wage earner and the mother, the principal homemaker.

At the same time, the survey data show that, for more than 70 percent of dual-earner families, having both parents work full-time is compatible with a happy marital relationship. And they show that nearly 45 percent of breadwinner-homemaker families argue about chores and responsibilities, despite following the time-tested division of labor. Couples planning to embark on parenthood would do well to reach a clear-cut understanding about who will be doing what chores and who will be handling which household responsibilities. Be flexible, but men: Do more than your wife expects!

Nicholas Zill is a psychologist and survey researcher who has written on indicators of family and child well-being for four decades. Prior to his retirement, he was the head of the Child and Family Study Area at Westat, a social science research corporation in the Washington, D.C., area.

1. James L. Peterson and Nicholas Zill, “Marital Disruption, Parent-Child Relationships, and Behavior Problems in Children,” Journal of Marriage and Family 48, no. 2 (1986): 295-307.

2. Suzanne M. Bianchi, Melissa A. Milkie Liana C. Sayer, and John P. Robinson, “Is Anyone Doing the Housework? Trends in the Gender Division of Household Labor,” Social Forces 79, no. 1 (2000): 191-228.

3. Bobbie Mixon, “Chore Wars: Men, Women and Housework,” National Science Foundation, April 28, 2008.

4. Quentin Fottrell, “33% of mothers spend 60 hours a week on mom-related tasks,” Marketwatch, May 9, 2015.