Highlights

- A recent study finds that single mothers who expect to lose benefits from the EITC upon marriage are 3.5 percentage points less likely to marry than those whose benefit would stay the same or increase if they married. Post This

- The study also found that the potential loss of benefits from the EITC increases the likelihood of cohabiting for unmarried moms by 3.5 percentage points. Post This

Both of my parents were born during the Great Depression. Both also have master’s degrees in accounting; plus, my mom has an additional master’s in taxation. In short, I grew up in a household where knowledge of the tax code was a tool used in the service of saving money, and where such frugality was treated like a moral virtue. My own motto when preparing an income tax return is “render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s—and not a penny more.”

Why, then, am I married despite the marriage penalties in the tax code? Quite simply, I’m married because I expected the benefits of marriage to far outweigh its tax costs. Others have found the expected costs high enough to eschew marriage, as Katherine Michelmore convincingly demonstrates in her recent article in the journal, Review of Economics of the Household. She found that single mothers who expect to lose benefits from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) upon marriage are 3.5 percentage points less likely to marry than those whose benefit from the EITC would stay the same or increase if they married.

Rational choices at the individual level depend on resources. Michelmore calculated that the average unmarried woman receiving EITC benefits would receive $1,300 less in the year following marriage. This is important considering that at lower income levels, $1,300 is much more likely to be spent on food or rent than on luxury goods. The delight that might come from treating the kids to an afternoon at the waterpark is rather irrelevant if there isn’t enough money to pay the water bill. In other words, you can’t really compare someone trying to decide if the marriage penalty is worth it to someone who can’t afford to consider taking a penalty at all. In fact, especially for working-class and lower-class individuals, $1,300 is a sizable enough sum to make marriage seem like a luxury good.

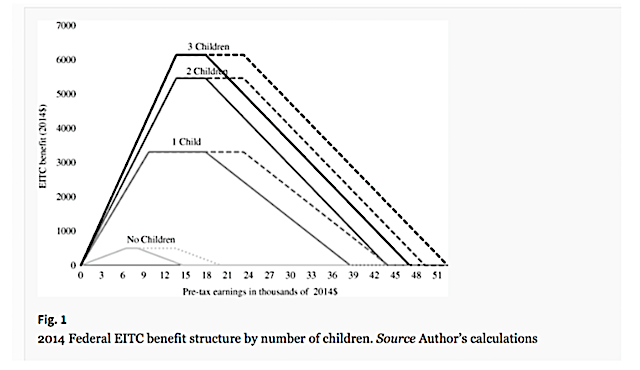

Michelmore doesn’t let us forget that information is also a resource: single mothers’ marriage decisions depended more on whether they faced a penalty of at least $500 than on the actual dollar amount of the penalty. Just as Review of Economics of the Householdprobably isn’t a widely read title among those who are not economists or scholars, details about the marriage penalty in the EITC aren’t widespread either. Some women actually see an increase in EITC benefits upon marriage, and most women don’t know exactly what changes they would face if married. That’s because as earned income rises, benefits phase in, plateau, and then phase out again. The phase-in period depends upon the number of children but not marital status, whereas the phase-out period depends on both. Michelmore made this complex structure accessible with this figure:

EITC benefits phase out more slowly for married couples than for singles—the married can get the same benefit level with higher incomes that singles can. However, there’s also a clear marriage penalty in that earnings for couples don’t have to be anywhere near twice as high before benefits phase out. Whether a single mother gains or loses income upon marriage depends upon where her income and her income summed with that of her potential spouse fall on these curves. Couples with unequal incomes typically receive marriage bonuses, while those with more similar earnings often receive marriage penalties. It is hardly surprising that many would not know the precise dollar impact of their decision. But even without what economists call “perfect information,” single mothers appear to have enough information about the marriage penalty in the EITC that it affects their relationship behavior. (Michelmore’s sophisticated analysis exploited differences in benefit levels over time and between states to show that benefits really mattered).

So, if facing a loss in EITC benefits makes single mothers 3.5 percentage points less likely to marry, how does the EITC affect cohabitation? According to the study, it increases the likelihood of cohabiting by 3.5 percentage points. Clearly, by moving in with a partner instead of marrying, single mothers retain some of the benefits of a partnership without incurring the tax penalty, but to consider this a wash would be inaccurate. Michelmore refers to “distortions” in marriage and cohabitation decisions caused by the EITC marriage penalty. Someone like me immediately jumps to thinking about the individual and social costs of substituting cohabitation for marriage, but Michelmore, who doesn’t mention these costs, still values removing distortions that result in behavior individuals would not otherwise choose.

The individuals whose choices are distorted are not “average”: results were stronger among the least educated, among racial minorities, and among the never-married. Michelmore concluded that“eliminating the marriage disincentives in the EITC structure could have an impact on the marriage and cohabitation decisions of millions of low-income families.” Tax structures that help keep marriage a luxury good aren’t fair: they distance the poor from a basic human institution.

I was doubly advantaged in my marriage decision by having the income level to absorb the cost of any tax penalty and a background that helped me make an accurate assessment of its relatively minor cost. Just knowing that there could be a cost might dissuade those living at lower earned income levels from marriage (particularly if they don’t know its size).

Tax law changes are moving in the right direction, but they still have a way to go. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 eliminated the marriage penalty for most couples—the 2018 federal income brackets allow a married couple to make exactly twice as much as a single person and still have the same tax rate (as long as combined income is less than $400,000). However, the marriage penalty is only gone for determining at what rate adjusted gross income is taxed: the basic structure for the EITC remains the same, with its marriage penalty intact.

I don’t want to be too pessimistic about the lack of recent changes with respect to the marriage penalty in the EITC, because there have been historical improvements. The penalty is far smaller now than when the EITC was introduced in 1975, with sizable reductions in the last decade. Momentum is in the right direction for removing distortions in marriage and cohabiting decisions. But if we don’t want marriage to be a luxury good, we need to continue to push for further changes in the EITC.

Laurie DeRose is a Research Assistant Professor at the Maryland Population Research Center at the University of Maryland at College Park and a senior fellow with the Institute for Family Studies. She is also Director of Research for the World Family Map project.