Highlights

For years now, the popular consensus in the UK has been that it's not marriage that matters to kids; it's whether their parents stay together that counts. The government-sponsored Families and Children Study illustrates this beautifully. This annual report shows how children in two parent families tend to have fewer behavioral and health problems, watch less TV, do better at school, and have higher aspirations. However, the study does not indicate whether there are any differences between married and unmarried two parent families because marital status was airbrushed from the study in 2003.

Despite established differences in marital stability from the government’s own earlier findings, married and cohabiting parents have henceforth been lumped together into a single category, as they are across a wide range of other government surveys, studies, forms, and policies on tax and benefits. But recent research by the Marriage Foundation affirms that these differences in stability remain significant and substantial.

In a new Marriage Foundation report, we used the well-being of teenagers as our outcome to test the assumption that as long as the parents stay together, children do equally well in unmarried and married-parent families. Together with Professor Spencer James of Brigham Young University in the U.S., we examined data from the annual British Household Panel Survey between 1991 and 2009, where 3,822 children aged 11-16 appeared in two or more consecutive years of data.

Our main outcome measure was “self-esteem,” which represents how teens see themselves and is a strong predictor of subsequent adult mental health, criminal behaviour, and economic prospects.1 We used a score based on five questions from the survey: “I feel I have a number good qualities;” “I certainly feel useless at times;” ”I am a likeable person;” “I am inclined to feel I am a failure;” and “At times, I feel I am no good at all.”

We then categorized teens by whether they were living in a family with continuously married parents, continuously cohabiting parents, or some other family type. We were extremely conservative in our categorizations, since some of the parents recorded in the data as “married” will definitely have been lone parents who had remarried, and some of the “other” parents may well have been married, but the data was unclear.

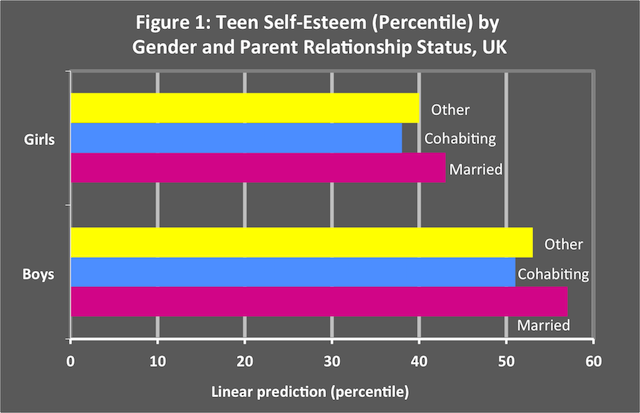

The results came as a big surprise. We compared children on the basis of their age and gender, the year in which the data was recorded, and the education and income of their mother. Taking all of these factors into account, teens in married families had higher self-esteem than teens in either of the other two family types. Teens living with two parents who were not married but still together were statistically no better off than teens living with only one parent.

There were two other differences. The biggest—roughly double the marriage effect—was that girls tended to have lower self-esteem than boys. The smallest—less than half of the marriage effect—was a reduction in self-esteem among children with better-educated mothers. But that was it. Child's age and year of survey made no difference. Nor did mother's income.

None of these differences were especially large, which is good news in that teens are neither condemned to a life of misery, nor guaranteed a life of unbridled happiness, purely on the basis of their gender or family background. But there is clearly something happening in married-parent families that is qualitatively different from unmarried cohabiting families, even where the parents are still together.

Self-esteem has long been associated with closeness and trust in relationships. The underlying differences that cause married parents, regardless of education or income, to be more likely to stay together must be present in the relationship somewhere. So, it's plausible that teens are picking up on some aspect of the relative security or insecurity experienced by their parents.

One possibility is that the attitudes and rituals associated with marriage—such as discussions about weddings, celebration of anniversaries, expectation of commitment for life—are filtering down to the children.2

It's plausible that teens are picking up on some aspect of the relative security or insecurity experienced by their parents.

Another possibility is that children notice how married parents trust in one another. A recent study showed that when a couple is faced with a threat, holding hands reduced stress levels—but only if they were married.3

A third possibility is that children also see the negative ways that married and cohabiting parents handle conflict. My study of 236 new mothers a few years ago showed that compared to a quarter of married parents, nearly half of the cohabiting parents used a particular insecure pattern of arguing, where fathers were dismissive or indifferent, and mothers were defensive.

Although we controlled for mother's education and income in our teen self-esteem study, it’s also possible that married and unmarried parents differ in other ways that make their children feel more secure. These could range from the kind of neighborhood they live in and social connections they have, to the type of jobs their parents hold and how much time the teens spend with the parents themselves.

Whatever it is, the conclusion of our study is clear: some characteristic of their parents' marriage makes teens feel more secure about themselves and the world around them. Marriage boosts teens’ self-esteem.

Harry Benson is Research Director of the UK-based Marriage Foundation.

1. Trzesniewski, K., et al. (2006). “Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood.” Developmental Psychology, 42, 381–90.

2. Nock, S. (2009). “The growing importance of marriage in America.” Marriage and family: Perspectives and complexities, 302-324.

3. Coan, J. (2014). “Marriage as a moderator of threat-related hypothalamic regulation in straight and same-sex couples.” Paper presented at Society for Personality and Social Psychology Symposium. Austin, Texas.