Highlights

The marriage divide between more and less educated and affluent Americans is well known.1 But how does this divide actually play out in the ordinary lives of Americans? Here, we take up this question by looking at the links between education, marriage, and television viewing.

Excessive television consumption can be a marker for low levels of happiness and poor health among adults. Watching TV in moderation may indeed be a positive activity for many Americans. However, researchers have continually found high TV consumption to predict less happiness and life satisfaction among adults.2 Researchers have also found television consumption to be associated with poorer physical health and well-being overall.3 One study even found that for every hour of television people watch, average life expectancy falls about 22 minutes.4 This data does not necessarily indicate that watching TV—in itself—has such negative impacts on a person’s health. However, it does suggest that more TV time—at the very least—reflects a less healthy lifestyle among American adults.

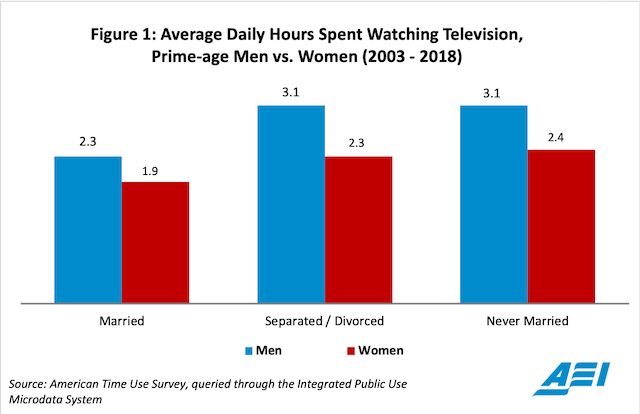

So, how does television consumption vary by class and marital status? Using data made available by the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), we can see that separated or divorced adults, and those who never marry, generally spend more time in front of the TV screen than their married peers (Figure 1). This difference is particularly pronounced among men, with divorced, separated, and never-married men watching an average of 3.1 hours of television every day, while married men spend only 2.3 hours per day watching TV. These results make some intuitive sense. Married adults are more likely to have additional responsibilities within the house, so they may engage in family-oriented activities other than watching television.

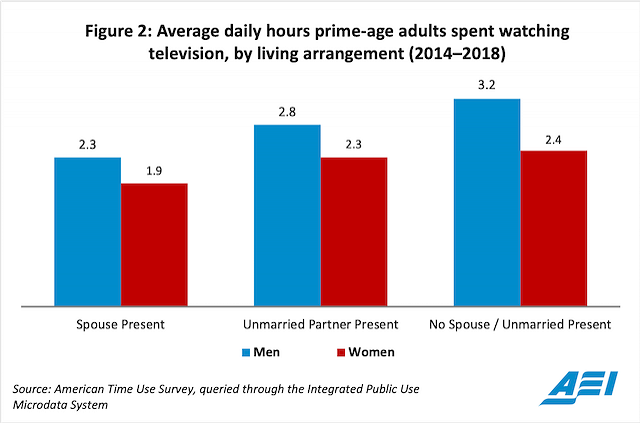

Some might respond to this explanation by arguing that marriage does not matter so much as living with another adult when it comes to determining how much time adults have to watch television. The idea that cohabiting adults share similar levels of responsibility as married couples may seem accurate. However, the data tell a different story. Prime-age adults living with an unmarried partner spend much more time watching television than those living with a spouse (figure 2). For women especially, cohabitation with an unmarried partner means watching nearly the same amount of television as women who live alone.

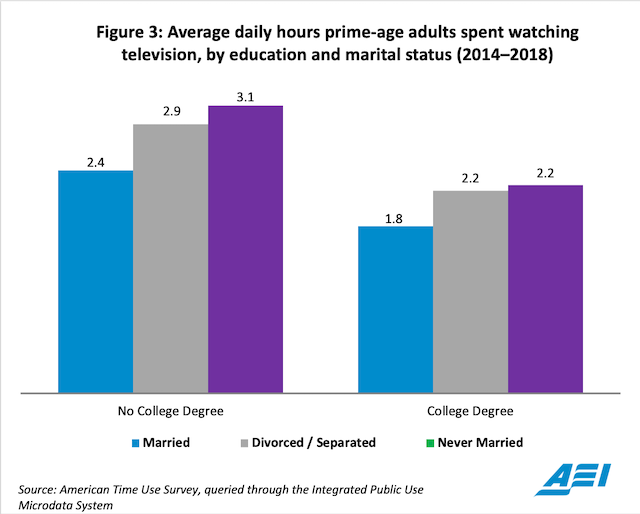

Additionally, when looking at the groups of adults who are most impacted by the marriage divide, we find that these groups tend to experience a double-disadvantage in television consumption. Across educational groups, divorced, separated, and never-married adults spend significantly more time watching television than married adults (figure 3). But marital status has the largest impact on people without a college degree.

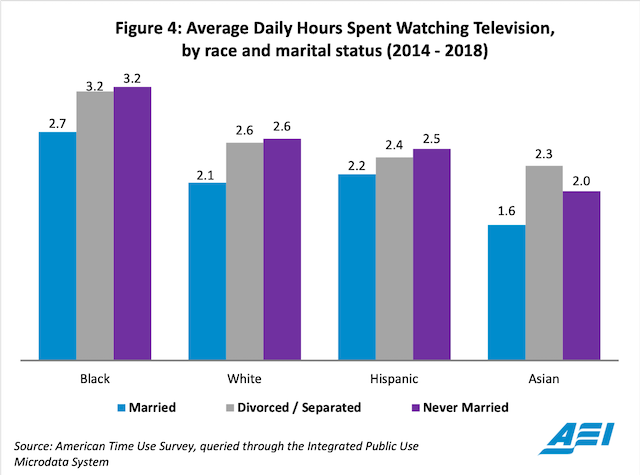

A similar story develops when looking at TV viewing habits by race and ethnicity. Within each racial and ethnic group, married adults spend less time watching TV than divorced, separated, and never-married adults (figure 4). However, unmarried White, Black, and Hispanic adults spend much more time watching television than Asians—a group that has escaped some of the concerning trends in the marriage divide.

The data presented here reflect the reality that marriage continues to be an important anchor for Americans’ lives.5 Marriage provides structure and purpose, and it often fills people’s days with rewarding activities, whether that be taking a child to soccer practice, sharing a meal with family, or engaging in religious services with one’s spouse. Prime-age adults who experience unsuccessful marriages or who never marry tend to spend more hours in the day in front of the television screen, which likely has important ramifications for the happiness and satisfaction of these groups.

Without the anchor of marriage, feelings of isolation and unhappiness in many Americans may be compounded by excessive TV consumption. Perhaps most concerning is that excessive television viewing may not be intentional but is likely used as a tool to fill vacant time these adults would otherwise spend on more rewarding activities. In looking at the data surrounding television consumption, we see a prime example of how the marriage divide impacts the every-day lives of Americans.

Peyton W. Roth is a Research Assistant in poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute. W. Bradford Wilcox is a Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and a Professor of sociology at the University of Virginia.

1. W. Bradford Wilcox and Wendy Wang, “The Marriage Divide: How and Why Working Class Families Are More Fragile Today,” Opportunity America-AEI-Brookings Working-Class Group, 2017.

2. Bruno S. Frey, Christine Benesch, Alois Stutzer, “Does watching TV make us happy?,” Journal of Economic Psychology, 28 (2007): 283–313; Claudia Schmiedeberg and Jette Schroder, “Leisure Activities and Life Satisfaction: an Analysis with German Panel Data, “Applied Research in Quality of Life, 12 (2017): 137–151; Juncal Cunado and Fernando Perez de Gracia, Does Media Consumption Make Us Happy? Evidence for Spain,” Journal of Media Economics, 25 (2012): 8–34; David A. Frederick, Gaganjyot Sandhu, Patrick J. Morse, Viren Swami, “Correlates of appearance and weight satisfaction in a U.S. National Sample: Personality, attachment style, television viewing, self-esteem, and life satisfaction,” Body Image, 17 (2016): 191–203.

3. Verity J. Cleland, Miuchael D. Schmidty, Terence Dwyer, Alison J. Venn, “Television viewing and abdominal obesity in yound adults: Is the association mediated by food and beverage consumption or reduced leisure-time activity?,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87 (2008): 1148–1155; Katrien Wijndale et. Al, “Television viewing time independently predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: the EPIC Norfolk Study,” International Journal of Epidemiology, 40 (2011): 150–159.

4. J Lennert Veerman et. Al, “Television viewing time and reduced life expectancy: A life table analysis,” British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46 (2011): 927–930.

5. Regression analysis confirmed that marital status, sex, and education level, race, and Hispanic ethnicity are all significantly associated with the amount of time adults spend watching television (p < 0.001).