Highlights

Sweden, in the view of many progressives, is the closest thing we have to the Promised Land. Among other things, the Swedish welfare state has done an exceptional job of fostering an egalitarian income distribution and minimizing poverty. The generosity of the Swedish welfare state has led some progressives to claim that the impact of recent family changes—e.g., increases in divorce, single parenthood, and nonmarital childbearing—is minimal on Swedish children.

Last year, for instance, Paul Krugman argued that family structure didn’t seem to matter much for Swedish kids, “perhaps because the welfare state is so strong” there. The thinking here is that family structure need not matter for children’s well-being, so long as parents are guaranteed a decent income, as they are in Sweden.

There is only one problem with this theory: it doesn’t capture the emotional and social costs of family instability and single parenthood that play out apart from the economic toll associated with family breakdown. Because, even in Sweden, the evidence continues to mount that family structure matters.

Even in Sweden, the evidence continues to mount that family structure matters.

For instance, as I noted last year, a 2003 Lancet study of the entire population of Swedish children found that “children in single-parent families were about twice as likely to suffer from serious psychological problems, drug use, alcohol abuse, and attempted suicide, compared to children in two-parent families.”

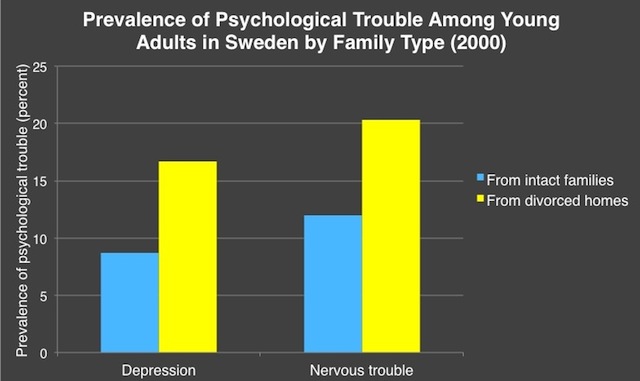

Now, there is more evidence that family structure matters, even in Sweden. A new study of divorce (which included separation for cohabiting parents) finds that young adults from divorced homes are 48 percent more likely to experience psychological problems than their peers from intact families. In 2000, 17 percent of young adults from divorced homes were depressed, compared to 9 percent from intact families; and 20 percent from divorced homes had “nervous trouble” compared to 12 percent from intact families.

Source: Gähler, M., & Garriga, A. (2013). Has the association between parental divorce and young adults’ psychological problems changed over time? Evidence from Sweden, 1968-2000. Journal of Family Issues, 34(6), 784-808. doi:10.1177/0192513X12447177

The link between divorce and young adults’ psychological problems in Sweden is largely accounted for by family dissension and, to a lesser extent, economic hardship. So, yes, as Krugman might suspect, money matters. But the dissension associated with a family breakup was more important than the money in explaining why divorce was linked to psychological problems among Swedish young adults.

Finally, the study also found evidence that the divorce–psychological problems link for individual young adults may be weakening in Sweden. Good news? Not necessarily. This study, as well as others, finds that marriage continues to lose ground, and family instability continues to rise in the Land of the Midnight Sun. Moreover, according to this new research, “psychological problems have increased substantially among young Swedes during recent decades” among young adults from both divorced and intact homes.

It’s possible that any Swedish spike in psychological problems among young adults is linked to the nation’s economic changes: economic globalization, the economic downturn, etc. But it’s also possible that the rising tide of family instability in Sweden is exacting a psychic toll on Swedish young adults in general. In other words, if family effects are not just individual but also communal, then even young adults from intact families may suffer from the fact that fewer of their friends and family members are enjoying loving, committed relationships that go the distance.