Highlights

Congratulations, class of 2015. You have reached a major milestone in life: graduating from college. One reason this is a big milestone is that you’re now one of the fortunate few. Today, only about one-third of Americans get a college degree. Those of us who move in college-educated circles can lose sight of this fundamental social fact. But you’re privileged, now, in ways that most of your fellow Americans are not.

You will have better job opportunities, make more money, and end up happier, on average, than your fellow citizens who did not complete a college degree. The social scientific evidence tells us that Americans with four-year college degrees make about 98 percent more per hour than do their fellow Americans without a degree. On average, that means that you will make at least $32,000 more per year in midlife than your peers who don’t have a high school degree. This is one reason why college is worth it. Even factoring in the cost of paying thousands of dollars for college tuition, your degree is a bargain. That’s because, as David Leonhardt wrote in the New York Times, “Over the long run... Not going to college [would] cost you about half a million dollars.”

But life is about more than money, as we all know. Today, Americans with college degrees also enjoy stronger connections to many of the institutions that give our lives meaning, direction, and purpose: from marriage to the Boy Scouts to church and the like. My own research indicates that college-educated Americans today are much more likely to get and stay married. In fact, you may have heard that almost one in two marriages will end in divorce. Not true for those with a college degree. The relative probability of divorce is about 65 percent lower for the college-educated among us. This is just one of the ways in which college-educated Americans enjoy stronger connections to the core institutions that give our lives meaning and purpose.

College-educated Americans enjoy stronger connections to the core institutions that give our lives meaning and purpose.

As Durkheim—the great French sociologist—might predict, all this social integration translates into higher levels of happiness on the part of the college-educated. In fact, my analysis of the General Social Survey indicates that college-educated Americans are about 24 percent more likely to be “very happy” than their less-educated peers. And being connected to others through marriage and churchgoing explains a substantial share of this college premium in happiness. Indeed, these measures of social integration—especially marriage—do a better job of accounting for the college premium in happiness than does income.

All this means, I think, that you owe a profound debt of gratitude to the family and friends who helped make your graduation from college possible. I’m thinking especially of your parents. The emotional, practical, and financial sacrifices made by your parents for you, and for your college education in particular, have proved to be incredibly important. Let’s take a moment to thank mom and dad.

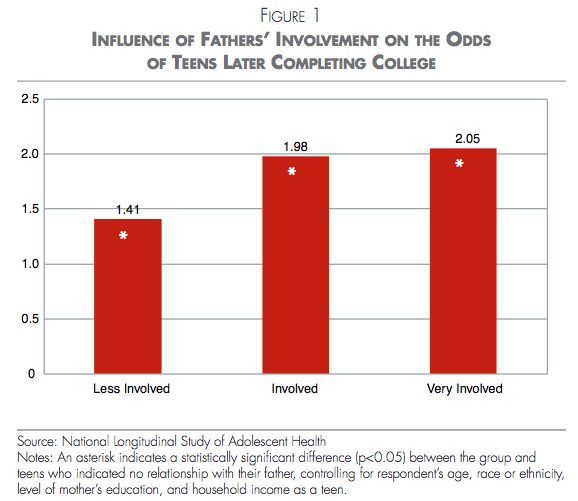

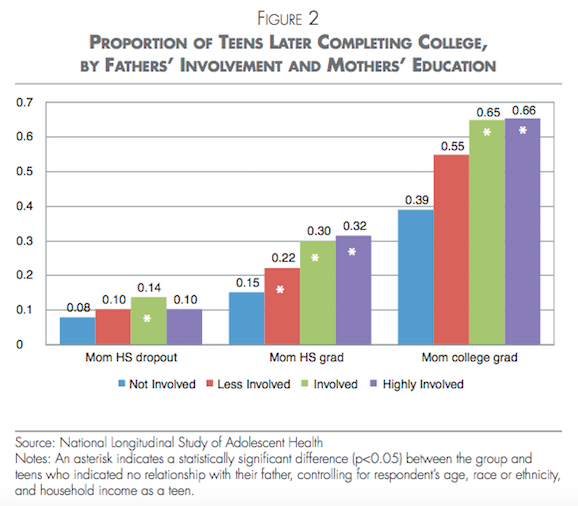

Those of you who were fortunate to have involved fathers should feel grateful. My own study found that young adults who had involved dads when they were teenagers were about twice as likely to graduate from college, compared to young adults who did not have much or any relationship with their father. This finding brings to mind the words of President Obama: “Of all the rocks upon which we build our lives, we are reminded today that family is the most important. And we are called to recognize and honor how critical every father is to that foundation. They are teachers and coaches. They are mentors and role models. They are examples of success and the men who constantly push us toward it.” Caitlin Rider, a graduating senior at U.Va., echoed the president’s words in this way to me: “I am grateful for my father who never hesitated to vocalize [the following] words to me over the years. My father always responded to news of both successes and failures with ‘I'm proud of you.’ This small phrase has carried me through it all.”

Of course, for many of us, no one has played a more central role in our passage through life than our mother. In fact, if you were like me, and you grew up without a father in your life, you owe a special debt of gratitude to your mother for shouldering the burden of parenthood all on her own. I cannot begin to imagine all the practical work—the meals, the laundry, and the carpooling—that my mom invested in me and my sister over the course of our early years. Nor can I imagine the emotional work—all the listening, the wisdom, and the tending that she devoted to us as we grew up.

Indeed, with the publication of Robert Putnam’s powerful new book, Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, we’re hearing a lot more about the powerful role that parents play in the lives of their kids. One way that parents benefit their kids is by speaking to and reading to them. As all of you budding sociologists know, there is now a huge class divide in this type of engagement. Putnam points out, for instance, that children of parents with professional degrees hear about 19 million more words than children from working-class families by the time they reach kindergarten. These class-based parenting differences have staggering implications for what Putnam calls the “opportunity gap” in America because children who get more language from their parents are much more likely to thrive in school.

Class-based parenting differences have staggering implications for the ‘opportunity gap’ in America.

In talking about this opportunity gap, and the importance of parents reading to their kids, Putnam often mentions that children from more advantaged homes enjoy more “Goodnight Moon time” than kids from poor and working-class families. That sure hit home for me, as that was a childhood favorite of mine when it came to bedtime stories with my mom. I really don’t know where I’d be without my mom, who was literally the rock upon which my life was built. I know I’m not alone in this view. Peter Stebbins, a graduating senior at U.Va., underlined the ways in which his parents’ example inspired him to excel in college: “My mother and father didn’t need to stress the value of education, or the importance of excelling relative to peers. Rather, they had an infectious enthusiasm for the academic mindset, and it instilled in me a desire to feel the same joy and satisfaction they derived from expanding one’s knowledge and mental toolkit.”

So, again, to the parents of the graduating seniors out there who have sacrificed so much so that these young men and women could be here today, thank you.

Let me conclude with two important takeaways.

The first is that we live in a society that is profoundly unequal and growing more so by the day. Americans like you graduates are the fortunate few. Many of you will enjoy better opportunities and more income than your fellow citizens. As importantly, many of you will forge stronger social ties to families, charities, and churches than your fellow citizens. Your good fortune means, in my view, that you have duties. As the good book says, to whom much is given, much is required. For some of you, that will mean stepping into a job as a teacher at a school serving low-income students. For others, it will mean advancing public policies that close the opportunity gap between college-educated Americans and everyone else. And for still others, it will mean mentoring children in poor neighborhoods in our nation’s cities, suburbs, or small towns. But, whatever you do, mind the gap, and do what you can to close it.

To whom much is given, much is required.

Finally, at this stage of life, you often get the message—from parents, teachers, and peers—that you should focus now on your schooling and your work, to the exclusion of focusing upon your romantic or marital future. There is certainly some wisdom to this idea, as your future vocational success depends a lot on your performance over the next decade.

But let’s not forget that—for most of us—our family ends up being much more important than our education and our work. So for those of you who have already found someone special, it’s not the worst thing in the world to start thinking about your future. I was captivated by my future wife when I met her at U.Va. twenty-three years ago, and then devoted three years to pursuing her; I’m happy to report that we will be celebrating our twentieth anniversary this summer. She was definitely the best thing that happened to me at U.Va.

But for those of you who have not yet found the love of your life, keep your eyes open and take your relationships seriously over the next decade. As psychologist Meg Jay argues in The Defining Decade, a book about the twentysomething years, when it comes to relationships, young adults should not “settle” for “spending their twenties on no-criteria or low-criteria relationships that likely have little hope or intention of succeeding.” Regardless of when or whether you get married, Jay advises young adults like you to take the next decade seriously when it comes to relationships—that is, as an opportunity to grow in the virtues of love and commitment. That’s partly because, for many of you, one of these relationships is likely to end up in marriage. And even if a relationship doesn’t end in marriage, it is good to grow in the virtues that might sustain you in a marriage to someone else.

And that brings us full circle. As a department and a university, we are so proud of your achievements, and we are so grateful to the parents, grandparents, friends, mentors, and teachers who have made this moment possible. Please join me in giving a hand to the class of 2015 and to all those who have helped them to forge a path to this wonderful day at Mr. Jefferson’s University.

This article is adapted from the graduation address that Wilcox gave to the graduating class of sociology majors at the University of Virginia on May 16, 2015.