Highlights

Progressive scholars have emphasized economic explanations for the retreat from marriage, whereas conservative scholars have stressed shortfalls in public policy. In perhaps the most well-known account, sociologist William Julius Wilson argued that the shift to a post-industrial economy starting in the 1970s undercut the availability of good jobs for men, thereby making them less “marriageable.”1 In contrast, political scientist Charles Murray contends that the increased generosity of welfare benefits in the late 1960s and 1970s played a key role by reducing the need for male breadwinners in lower-income communities and thereby eroded the practical and normative importance of marriage.2

Studies find qualified support for both the liberal and the conservative position, though neither can fully account for either the overall retreat from marriage or the growing educational divide in marriage. Welfare benefits have been linked to higher rates of nonmarital childbearing and lower levels of marriage.3 But the evidence is mixed, and the explanatory power of welfare is modest at best.4 Likewise, economic restructuring—deindustrialization, deunionization, the declining ratio of men’s to women’s income, and, consequently, men’s diminished marriageability—also appears to have played a role in the retreat from marriage, especially among African Americans and the less educated.5 Nevertheless, economic factors account for only a modest portion of the dramatic retreat from marriage.6

The fact that neither public policy nor economics can fully explain the retreat from marriage suggests that we must incorporate cultural and civic factors into any serious consideration of family trends over the past half-century. In particular, shifts in attitudes, aspirations, and norms, coupled with declining participation in secular and religious civic institutions, have undercut the social pressure to marry, to have children within marriage, and to stay married. But let us be clear: By considering cultural and civic factors, we’re not advancing individualistic or “personal responsibility” explanations for the retreat from marriage. Culture and civil society are collectively produced, just as much as economics and public policy. Moreover, changing economic conditions have made some Americans particularly susceptible to cultural conditions that undercut marriage.7

Since the late 1960s, five cultural trends have been particularly consequential for marriage and family life. First, the rise of “expressive individualism”—the idea that personal desires trump social obligations—means that Americans feel less obligated to get and stay married, and have come to expect more fulfillment from marriage. In turn, rising expectations for marriage have made Americans more hesitant to marry, quicker to divorce, and less likely to believe that marriage and parenthood must be bundled together.8

Second, the changes in mores and behavior associated with the sexual revolution diminished the connection between sex, marriage, and parenthood, thereby making marriage less necessary and nonmarital childbearing more acceptable and more common.9 Third, second-wave feminism, which arose concurrently with women’s rising labor force participation in the 1960s and 1970s, fostered a sense of independence among women and raised their expectations for equality and intimacy in marriage, all of which reduced the imperative to get and stay married.10 Fourth, an increasing number of children were reared in nonintact families.11 Many became pessimistic about their own prospects for a lasting marriage, so they remained unmarried.12 Together these developments made a family-centered ethos less central to American life.

All these developments helped fuel the fifth cultural trend: what sociologist Andrew Cherlin calls the transition from a “cornerstone” to a “capstone” model of marriage. Men and women became less likely to see marriage as a foundation for adulthood, as the exclusive venue for sexual intimacy and parenthood, and as a “union card for membership in the adult world.”13 Instead, marriage became an opportunity for men and women to consecrate their arrival as successful adults, to signal that they were now confident they could achieve a fulfilling romantic relationship built on a secure, middle-class lifestyle. The advent of the capstone model of marriage means that more Americans see marriage as out of their reach, given the perceived economic and emotional requirements to get married nowadays.14 Consequently, Americans are spending less of their lives within the bonds of matrimony.

The collective result of these cultural changes is that a less family-oriented, more individualistic approach to relationships, marriage, and family life has gained ground since the 1960s. For instance, young adults have become less likely to associate parenthood with marriage. In the late 1970s, less than 40 percent of high school seniors thought that having a child outside of marriage was “experimenting with a worthwhile lifestyle” or “not affecting anyone else.” By the early 2000s, that figure stood at more than 55 percent.15 In sum, expressive individualism, the sexual revolution, feminism, the growing number of children reared in nonintact families, and the rise of the capstone model of marriage all coalesced to weaken the social and behavioral connections among sex, marriage, and parenthood. Consequently, stable marriage functions far less as an anchor and guide to adult life and to the bearing and rearing of children.

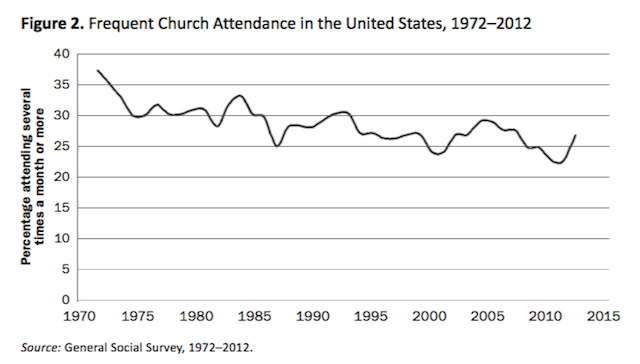

The retreat from marriage has been fueled by a parallel retreat in American civil society, especially with respect to religious participation. In Bowling Alone, political scientist Robert Putnam documented how many forms of secular and religious civic engagement, from membership in the Shriners to church attendance, have declined since the 1960s.16 Figure 2 shows the downward trend in regular religious attendance (attending several times a month or more). Civic institutions have traditionally supplied Americans with social solidarity, moral guidance, financial support, and family-friendly social networks, all of which reinforce the marriage norm and strengthen family life. In particular, religious attendance and belief have long upheld the institutional power and stability of marriage.17 Still, adherence to conservative religious beliefs without attending church regularly is associated with worse family outcomes, whereas combining adherence with regular attendance is associated with better family outcomes.18 This may explain why single parenthood is high in Arkansas, with its many nominal Baptists, and low in Utah, with its many active Mormons.

As we’ve seen, accounts that stress either economic factors or public policy (or both) in explaining the retreat from marriage in America don’t tell the whole story. First, cultural shifts that gathered steam in the late 1960s and the 1970s undercut a cornerstone model of marriage as the preeminent venue for sex, childbearing and childrearing, mutual aid, and economic support—all understood to be secured by an ethic of marital permanence. Second, participation has been declining in the secular and, especially, the religious institutions that long nurtured the social conditions conducive to strong marriages.

Excerpted with permission from The Future of Children, a collaboration of The Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University and the Brookings Institution. To download the full article, “One Nation, Divided: Culture, Civic Institutions, and the Marriage Divide,” click here.

W. Bradford Wilcox is the director of the National Marriage Project and an associate professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Virginia, a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Nicholas H. Wolfinger is a professor in the Department of Family and Consumer Studies and an adjunct professor of sociology at the University of Utah. Charles E. Stokes is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at Samford University.

- William Julius Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, The Underclass, and Public Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987); William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Random House, Inc., 1996).

- Charles Murray, Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950–1980 (New York: BasicBooks, 1984).

- Amy C. Butler, “Welfare, Premarital Childbearing, and the Role of Normative Climate: 1968–1994,” Journal of Marriage and Family 64 (2002): 295–313, doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00295.x; Irwin Garfinkel et al., “The Roles of Child Support Enforcement and Welfare in Non-Marital Childbearing,” Journal of Population Economics 16 (2003): 55–70, doi: 10.1007/s001480100108; Daniel T. Lichter et al., “Economic Restructuring and the Retreat from Marriage,” Social Science Research 31 (2002): 230–56, doi: 10.1006/ssre.2001.0728.

- David T. Ellwood and Christopher Jencks, “The Spread of Single-Parent Families in the United States Since 1960,” in The Future of the Family, ed. Daniel P. Moynihan, Timothy M. Smeeding, and Lee Rainwater (New York: Russell Sage, 2004), 25–65.

- Lichter et al., “Economic Restructuring”; Daniel T. Lichter et al., “Race and the Retreat From Marriage: A Shortage of Marriageable Men?” American Sociological Review 57 (1992): 781–99.

- Lichter et al., “Economic Restructuring”; Robert A. Moffitt, “Female Wages, Male Wages, and the Economic Model of Marriage: The Basic Evidence,” in The Ties That Bind: Perspectives on Marriage and Cohabitation, ed. Linda Waite and Elizabeth Thompson (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 2000), 302–19; David T. Ellwood and Christopher Jencks, “The Uneven Spread of Single-Parent Families: What Do We Know? Where Do We Look for Answers?” in Social Inequality, ed. Kathryn Neckerman (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2004), 3–78.

- James Q. Wilson, “Why We Don’t Marry,” City Journal 12, no. 1 (2002), http://www.city-journal.org/ html/12_1_why_we.html.

- Robert Bellah et al., Habits of the Heart (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1985); Andrew J. Cherlin, The Marriage-Go-Round (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009).

- George Akerlof, Janet L. Yellen, and Michael L. Katz, “An Analysis of Out-of-Wedlock Childbearing in the United States,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 111 (1996): 277–317; Steven Nock, “Marriage as a Public Issue,” Future of Children 15, no. 2 (2005): 13–32.

- Cherlin, Marriage-Go-Round; Stephanie Coontz, Marriage, A History: How Love Conquered Marriage (New York: Penguin, 2006).

- Larry L. Bumpass and James A. Sweet, “Children’s Experience in Single-Parent Families: Implications of Cohabitation and Marital Transitions,” Family Planning Perspectives 21 (1979): 256–60.

- On attitudes toward marriage, William G. Axinn and Arland Thornton, “The Influence of Parents’ Marital Dissolutions on Children’s Attitudes toward Family Formation,” Demography 33 (1996): 66–81; on marriage rates, Nicholas H. Wolfinger, Understanding the Divorce Cycle: The Children of Divorce in Their Own Marriages (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- Cherlin, Marriage-Go-Round, 139.

- Cherlin, Marriage-Go-Round; Coontz, Marriage, A History.

- W. Bradford Wilcox, The State of Our Unions (Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project/Institute for American Values, 2012).

- Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000).

- Annette Mahoney, “Religion in Families, 1999–2009: A Relational Spirituality Framework,” Journal of Marriage and Family 72 (2010): 805–27, doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00732.x; W. Bradford Wilcox, Soft Patriarchs, New Men: How Christianity Shapes Fathers and Husbands (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

- Wilcox, Soft Patriarchs.