Highlights

- Women who grew up religious are about 20% less likely to begin a cohabiting union in any given year than their non-religious peers. Post This

- Our results suggest there may be a “sweet spot” for marriage in the 20s: early 20s for direct-marriers, and late-20s for cohabiters. Post This

- Surprisingly, religious 20-somethings who marry directly without cohabiting appear to have the lowest divorce rates. Post This

The new marriage norm for American men and women is to marry around the age of 30, according to the U.S. Census. Many young adults believe that marrying closer to age 30 reduces their risk of divorce, and, indeed, there is research consistent with that belief. But we also have evidence suggesting that religious Americans are less likely to divorce even as they are more likely to marry younger than 30. This paradoxical pattern raises two questions worth exploring: Is the way religious Americans form their marriages different than the way marriages are formed by their more secular peers? And do religious marriages formed by twenty-somethings face different divorce odds than marriages formed by secular Americans in the same age group?

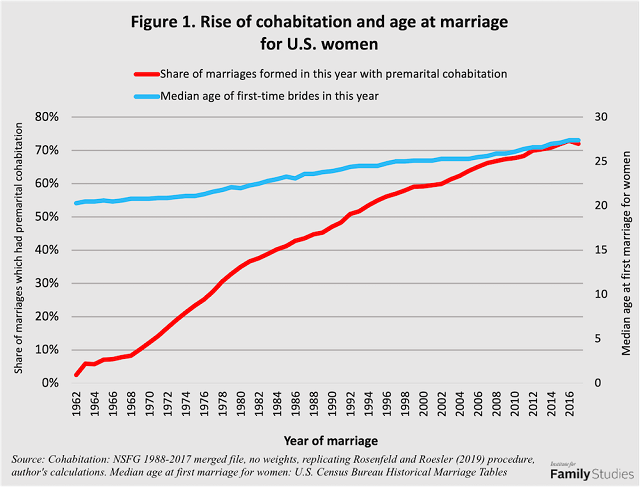

The answer to that last question is complicated by the role of cohabitation in contemporary family formation. Today, more than 70% of marriages are preceded by cohabitation, as Figure 1 indicates. Increased cohabitation is both cause and consequence of the rise in the age at first marriage. But what most young adults do not know is that cohabiting before marriage, especially with someone besides your future spouse, is also associated with an increased risk of divorce, as a recent Stanford study reports.

So, one reason that religious marriages in America may be more stable is that religion reduces young adults’ odds of cohabiting prior to marriage, even though it increases their likelihood of marrying at a relatively young age. Accordingly, in this Institute for Family Studies research brief, we explore the relationships between religion, cohabitation, age at marriage, and divorce by looking at data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG).

Researching Religion and Family

To address the questions addressed in this research brief, we merge data from the National Survey of Family Growth from 1995 to 2019, using responses from over 53,000 women ages 15 to 49 to recreate their individual-level family histories. (We focus on women because men were not included in the NSFG until recently.)1

The NSFG included two important questions about religion: first, the respondent’s current religious affiliation, and second, what religion they were raised in. Current religious affiliation is not a very informative variable for understanding how religion influences family life because, for example, marriage might motivate people to become more religious (or cohabitation might motivate people to become less religious). But religious upbringing (measured by a woman’s reported religious denomination “in which she was raised” around age 14) occurs before the vast majority of marriages or cohabitations, so is not influenced by them.

Thus, we explore how religious upbringing influences family life. Young adults don’t choose what religion they’re raised in, so this is about as close as we can get to what researchers call “exogenous” treatment, meaning something like experimental conditions. But because religious upbringing could be correlated with many other variables, we also include some important controls: a woman’s educational status in each year of her life (i.e., enrolled in high school, dropped out, enrolled in college, college graduate, etc.), her race or ethnicity, her mother’s highest educational attainment, and whether she grew up in an “intact” family. We also control for survey wave and decade.

Does Religion Influence Marriage and Cohabitation?

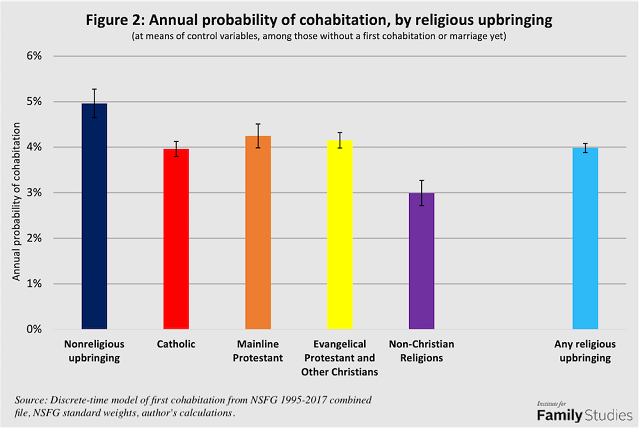

In the 1960s, about 5% of newlyweds cohabited before marriage. In the 2010s, it was more than 70%, an enormous increase. After incorporating the effects of control variables, Figure 2 shows2 that in a typical year of life, about 5% of nonreligious women ages 18-49 who have not yet married or cohabited will begin a cohabiting union. That figure is nearer 4% for women with a Christian upbringing, nearer to 3% for women with a non-Christian religious upbringing (i.e., Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses as well as Jews, Muslims, Hindus, and others), and about 4% for religious women on the whole. In other words, after controlling for a variety of background factors, women who grew up religious are about 20% less likely to begin a cohabiting union in any given year than their non-religious peers. As a result, by age 35, about 65% of women with a non-religious upbringing had cohabited at least once, versus under 50% of women with a religious upbringing. Not only does religion reduce the odds that young adults cohabit, it also increases the odds that they marry directly, or without cohabiting first.

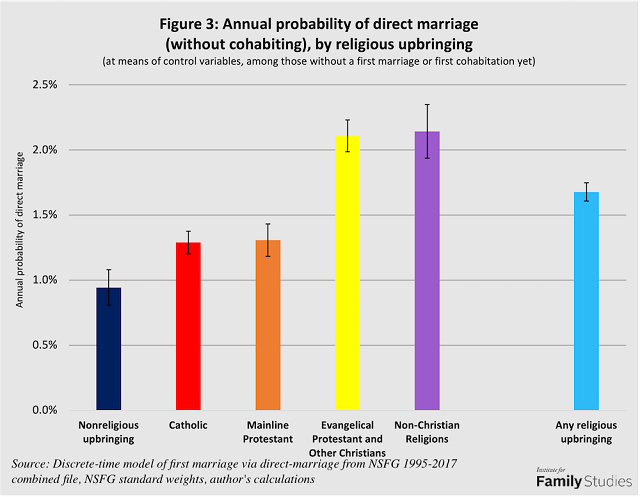

Figure 3 illustrates3 the links between religion and what we call direct marriages, that is, marriages that did not include premarital cohabitation. The trends depicted below in Figure 3 show up in similar form for all marriages, but direct marriages are particularly important because they are a closer proxy for the “traditional” relationship pathways promoted by many religions.

For women with a non-religious upbringing who have not yet married or cohabited, about 1% are likely to begin a direct marriage in a given year. For religious people generally, it’s a little more than 1.5%. But for women with Evangelical Protestant or Non-Christian Religious upbringings, the rate of entrance into marriage is over 2%: this is twice the rate of entrance into “direct” marriage. By age 35, about 28% of women with a non-religious upbringing had entered a direct marriage without cohabiting, compared to approximately 43% of women with a religious upbringing. In other words, religiosity is associated with vastly greater likelihood of going directly from singleness to a married union, and generally at younger ages.

Overall, then, religion greatly influences the nature and age of relationship formation. Young women raised in a religious home cohabit less, but they marry more, and especially earlier: in this sample tracking marriage patterns over the last 40 years, women with non-religious upbringings wed around age 25, religious women wed generally around age 24, and women with Evangelical Protestant upbringings wed around 23.5.

Does Religion Influence Breakup and Divorce?

Earlier marriage is a known risk factor for divorce. Premarital cohabitation is too. Since religiosity tends to motivate earlier marriage but less cohabitation, the effects on divorce are not easy to guess. What we really want to know is: conditional on getting married, do religious people get divorced less?

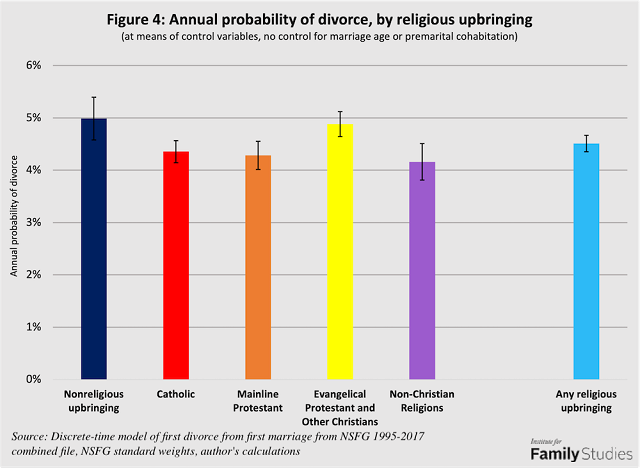

The answer appears to be yes. Without controls for age at marriage or an indicator for premarital cohabitation, women with a religious upbringing do have slightly lower likelihoods of divorce. As shown4 in Figure 4, the annual divorce rate among married women with a nonreligious upbringing is around 5%. For religious women, it’s around 4.5%. The effect is clearest for Catholic and Mainline Protestant women, and less clear for Evangelical Protestant women. Overall, if we control for basic socioeconomic background and a woman’s educational career trajectory, the typical marriage of a woman with a religious upbringing is about 10% less likely to end in divorce within the first 15 years of marriage than the typical marriage of a woman with a non-religious upbringing.

Adding controls for age at marriage yields about the same results, suggesting that even though religious people get married younger, their divorce rates are still a bit lower. But it may just be that religious people cohabit less, and that is what drives the reduction in divorce. To assess this point, we analyze only marriages with no premarital cohabitation, and find no effect of religion: women with a religious upbringing have about the same likelihood of divorce as other women with the same relationship history and socioeconomic status. Most of the benefit of religiosity in terms of reducing divorce occurs because religious marriages are more likely to be direct marriages, rather than marriages with premarital cohabitation. In other words, one reason that women raised in a religious home are less likely to divorce is that they are less likely to cohabit prior to marrying.

But while less cohabitation explains most of the benefit, it does not explain all of it. We also estimated specific divorce rates by marital duration for marriages of women with religious or non-religious upbringings, split by the age at which they got married. Because this creates very small sample sizes, differences by religion were not always statistically significant, so results must be interpreted with caution.

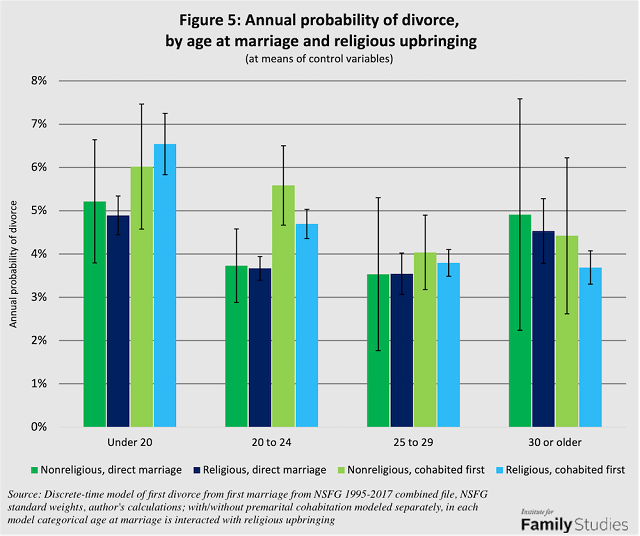

Figure 5 shows5 the estimated annual divorce probability with all the same control variables, but with estimates produced separately for women with different religious upbringings and marriage types.

Figure 5 makes it possible to answer three specific questions: what is the effect of premarital cohabitation? What is the effect of age at marriage? And what is the effect of religious upbringing?

Premarital Cohabitation

Starting with premarital cohabitation, women with direct marriages (the darker-colored bars) tended to have lower divorce rates than women with the same religious background and the same age at marriage, but who married after cohabiting. This was especially true for religious women who married before age 25. For women marrying after age 30, the relationship seems to flip, though estimates are less reliable because, since we can only observe women until a maximum of age 44 in some survey waves and age 49 in others, women who married past age 30 had fewer years of marriage included in the analysis. But particularly for youthful marriages before age 20 or in the early 20s, cohabiting before marriage appears to be a major risk factor for divorce.

Age at Marriage

Age at marriage also matters, but in different ways for different groups. For religious women who cohabitated before marriage, age is extremely important. Women raised in a religious household who cohabit have very high divorce risks if they marry before age 20, but the lowest risks of any group of women who marry in their 30s. For women raised in a nonreligious home who cohabited before marriage, delaying marriage from the teens into the mid-20s may reduce divorce risk, but delaying marriage into the 30s doesn’t appear to lower the divorce risk at all, and may even be associated with a higher risk. That is to say, for nonreligious women who cohabitated before marriage, there is something like a Nike-swoosh shape to divorce risks. Our results parallel the work of sociologist Nicholas Wolfinger here. For these women, getting married in their late 20s maximizes marital stability.

For religious women who had direct marriages, marrying before age 20 does have some risks, but by age 20-24, age at marriage doesn’t appear to carry as much weight: religious women who marry directly have the same likelihood of divorce if they get married at age 20-24 or age 25-29, with a modest increase in their 30s.

And finally, the same trend holds for non-religious women in direct marriages: they have somewhat elevated divorce risks if they marry before age 20, low and stable risks during their 20s, and somewhat higher risks if they marry in their 30s. However, because the sample size of these non-religious women marrying in their twenties is much smaller, error margins are extremely wide.

These results suggest delaying marriage doesn’t always make it more stable. If marriage is delayed by cohabiting instead, divorce risks are higher: non-religious women with prior cohabitation who married in their late 20s or 30s have the same or higher divorce rates as non-religious women who married directly or without cohabiting first, in their early 20s. Postponing marriage by substituting cohabitation may not reduce divorce risks. Moreover, for many groups, despite not observing many latter-marriage years where divorce might have occurred, divorce risks among those who marry at age 30 or older rose for many groups. Our results suggest there may be a “sweet spot” for marriage in the 20s: early 20s for direct-marriers, and late-20s for cohabiters. Postponement beyond that age does little for marital stability, judging by the NSFG data.

Conclusion

It is commonly believed that postponing marriage until the late-20s or early-30s reduces the odds of divorce, because greater maturity results in a wiser choice of a partner, and there’s some truth to this. However, there’s a significant complexity under the surface: the life orientations associated with delayed marriage are often also associated with (and even causal of) greater acceptance of premarital cohabitation, which is also linked to a higher risk of divorce. The net result of this is that life orientations that motivate earlier marriage, like religiosity, do not necessarily create the higher likelihoods of divorce usually associated with early marriage because they discourage cohabitation. Yes, very young marriage still has risks (as does very late marriage), but religious upbringings seem to partly compensate for those risks, especially among women marrying in their 20s.

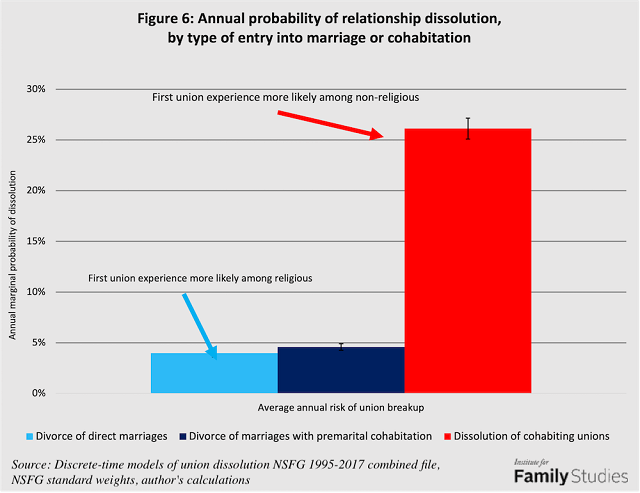

Our results also suggest that religion fosters relationship stability by pushing young adults away from cohabitation, which is highly unstable, and towards marriage, which is much more stable. It’s notable that figure 5 did not show meaningful differences in divorce rates between religious and non-religious women who had the same relationship histories: religion seems to impact relationships mostly by changing the kind of union a woman enters in young adulthood, not its durability once formed. Insofar as religion changes the type of union that women begin as young adults, and since dissolution likelihoods vary widely by union type, the effect of religion on women’s experience of union instability can be huge. Figure 6 provides a simple illustration6 of divorce or breakup risk by year, by union type.

Women who were raised religious are more likely to have a first union which is a direct first marriage, and so their first unions are more likely to experience breakup risks similar to the light blue bar at left. Non-religious women are much more likely to cohabit as their first union, which has astronomically higher breakup risks, as shown in the red bar at right.

The effect of cohabitation on marriage is indeed statistically significant (premarital cohabitation increases divorce probabilities by about 15%), but the biggest effect religion has on union stability isn’t about what happens once a woman is married, but more about her relationship choices before marriage—the fact that she did get married, rather than start a series of cohabiting relationships. To the extent that the effects associated with religious upbringing are causal, they show that religiosity could dramatically reduce women’s experience of relationship instability in early adulthood.

What remains unclear is how religion may foster more stable marriages. There are three broad possibilities: religion might induce people to “make lemons out of lemonade,” it might give people institutional or community support, or it might positively alter the quality of romantic pairings.

The first explanation is simple, if pessimistic. If religion induces women who would have entered a cohabiting union to get married instead, maybe those marriages aren’t better quality than the cohabiting union would have been, but because of their religious views, these women choose to not divorce.

The second possibility is that religion changes the experience of being married. Religious communities might provide institutional support to married couples: other married couple friends to provide peers and support, community or pastoral interventions to correct spousal behavior, material or financial support in times of hardship, etc.

And finally, religion may change exactly who women marry in important ways. First, religion could alter the potential spouses to which women are exposed. Via church communities, religious women may be able to access a larger and more marriage-friendly pool of potential spouses. Second, religion could alter the criteria that women have for selecting partners. Knowing that cohabitation is disfavored and desiring the companionship of a committed union, religious women might more actively pursue “husband material” partners earlier in life than other women. Third, religion might alter the dynamics between partners in important ways. Religious women might look for spouses who share values, beliefs, or practices that are important for union stability. Sharing these values might reduce the potential for conflict down the road.

Exactly which of these factors is at work is difficult to say. But one way or another, this Institute for Family Studies research brief suggests that waiting to marry until you’re 30 does not always increase your odds of forging a stable marriage. Especially for religious men and women who avoid cohabitation, our analysis of the NSFG indicates that they can marry in their 20s without serious adverse divorce risks. The upshot of all this is that the religious model of marriage and family appears to boost the odds that young adults can marry before 30 without increasing their risk of landing in divorce court.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Brad Wilcox is Director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Family Studies.

1. We pool data in much the same way that Michael Rosenfeld and Katharina Roesler did in the Stanford study mentioned above, and are appreciative of correspondence with them and their sharing of replication files, which helped us to produce a comparable approach.

2. Note (Figure 2): Control variables include binary INTACT18 Yes/No; race/ethnic coded as Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Other; maternal educational attainment coded in four categories; time-varying respondent educational attainment and enrollment in six categories constructed from NSFG educational history data; time-varying dummy variables for decade; and non-time-varying dummy variables for survey wave in which a woman was sampled; time increments are annual with 5-year categorical codes for simplified reporting, however when single-year-of-age dummies are used results are essentially identical.

3. Note (Figure 3): Control variables include binary INTACT18 Yes/No; race/ethnic coded as Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Other; maternal educational attainment coded in four categories; time-varying respondent educational attainment and enrollment in six categories constructed from NSFG educational history data; time-varying dummy variables for decade; and non-time-varying dummy variables for survey wave in which a woman was sampled; time increments are annual with 5-year categorical codes for simplified reporting, however when single-year-of-age dummies are used results are essentially identical.

4. Note (Figure 4): Control variables include binary INTACT18 Yes/No; race/ethnic coded as Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Other; maternal educational attainment coded in four categories; time-varying respondent educational attainment and enrollment in six categories constructed from NSFG educational history data; time-varying dummy variables for decade; and non-time-varying dummy variables for survey wave in which a woman was sampled; time increments are year of marriage up to the year 16.

5. Note (Figure 5): Control variables include binary INTACT18 Yes/No; race/ethnic coded as Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Other; maternal educational attainment coded in four categories; time-varying respondent educational attainment and enrollment in six categories constructed from NSFG educational history data; time-varying dummy variables for decade; and non-time-varying dummy variables for survey wave in which a woman was sampled; time increments are year of marriage up to the year 16.

6. Note (Figure 6): Control variables include binary INTACT18 Yes/No; race/ethnic coded as Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Other; maternal educational attainment coded in four categories; time-varying respondent educational attainment and enrollment in six categories constructed from NSFG educational history data; time-varying dummy variables for decade; age at union formation in five categories; and non-time-varying dummy variables for survey wave in which a woman was sampled; time increments are year of union up to the year 16.