Highlights

- Child support data from the Census Bureau reveals that the new fatherhood is not benefiting the 18 million boys and girls who reside with their birth mothers but not their biological fathers as a result of separation, divorce, or non-marriage. Post This

- The most dismaying indicator of paternal non-involvement is the proportion of non-resident fathers who have had no contact with their children in the last year. Post This

- While married fathers of today are playing a more active role in their children’s lives than married fathers of yesteryear, many fathers who don’t live with their kids are doing little either to support their children or even interact with them. Post This

Nowadays, anywhere you go in middle-class neighborhoods of American cities, you see examples of men with young children doing things their fathers never did, such as bottle-feeding infants, changing diapers, pushing strollers, and taking toddlers to the playground while mother is working. Time-use surveys have found that married fathers in 2011 were devoting nearly three times as much time per week to child-care activities as married fathers did in 1965, though still only half as much time as mothers.1

Most pediatricians and developmental psychologists believe the trend toward more egalitarian, burden-sharing parenthood, and especially involved fathering, is all to the good. Unfortunately, my examination of child support data from the Census Bureau reveals that the new fatherhood is not benefiting the children who need it most.2 These are the 18 million boys and girls who reside with their birth mothers but not their biological fathers as a result of separation, divorce, or non-marriage.3 Many of these children are being raised by less educated and lower income parents. These children are not seeing more of their fathers, nor are more non-resident fathers bearing their share of financial responsibility for the well-being of their children. Instead, the government has taken a greater role in providing food and health care for them.

Non-Involvement by Non-Resident Fathers

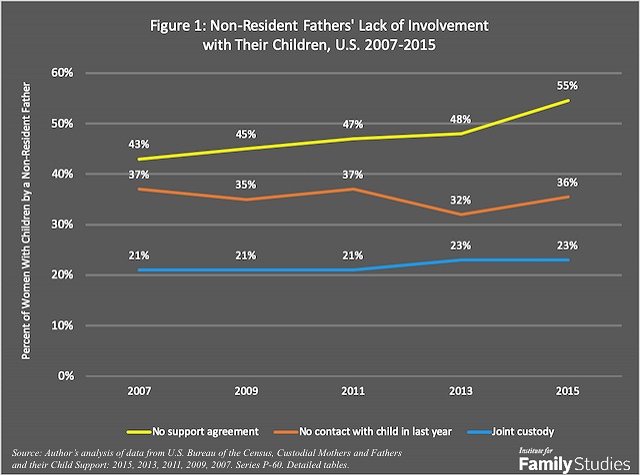

One of the most important things an unmarried (and non-cohabiting) couple can do to prevent conflict and maximize the chances of cooperative childrearing is to come to a formal agreement specifying a non-resident father’s visitation rights and what he will pay in the way of child support. But a majority of custodial mothers and non-resident fathers have never come to such an agreement, either formal or informal. Between 2007 and 2015, the proportion of families without such an agreement actually grew, from 43% to 55%, as shown in Figure 1. Not surprisingly, the fraction of mothers who received regular child support payments, which was already low, declined further over the same period, going from 37% to 32%.4

But don’t many couples have joint custody arrangements for their children nowadays? While joint custody is certainly more common now among divorced couples than it was 50 years ago, it is still only a minority of unmarried parents—less than a quarter—who have such arrangements. And there is no sign that joint custody is growing among unmarried couples, as may also be seen in Figure 1.

Perhaps the most dismaying indicator of paternal non-involvement is the proportion of non-resident fathers who have had no contact with their offspring in the last year. Surprisingly, that proportion has not diminished in recent years, fluctuating around 35% between 2007 and 2015, as shown in Figure 1.5

It is true that a majority of single mothers receive some form of non-cash support from non-resident fathers over the course of a year, such as birthday presents, diapers, clothes, or groceries.6 Although any kind of financial effort on the part of an absent dad may be needed, helpful, and welcomed by mother and child, occasional gifts are hardly a substitute for dependable support payments.

Social service agencies are no substitute for dedicated, loving, responsible fathers.

Non-Marriage Increases the Chances of Non-Support

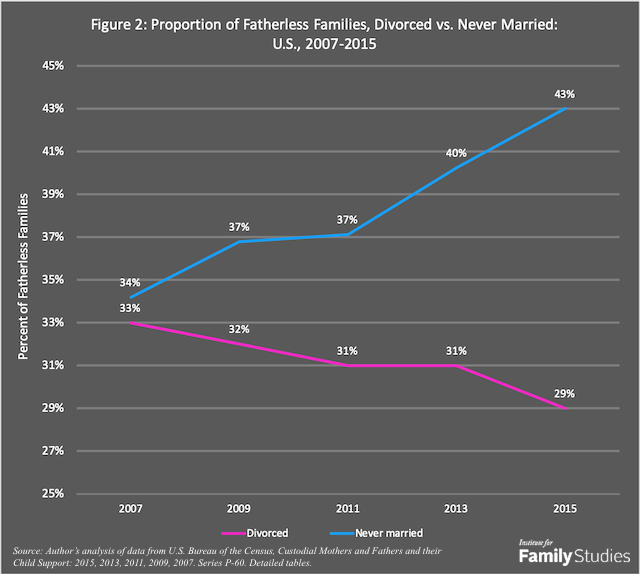

Underlying the decrease in child support agreements and payments was a decline in the proportion of unmarried families that resulted from divorce and an increase in the proportion who were never married in the first place. As a fraction of all fatherless families, never-married couples rose from 34% in 2007 to 43% in 2015, as shown in Figure 2. Over the same period, divorced couples declined from 33% to 29% of families headed by women with children from a non-resident father. (The remaining portion consisted of couples who had separated but not divorced and mothers who had divorced and remarried or entered into a first marriage with someone other than the father.)

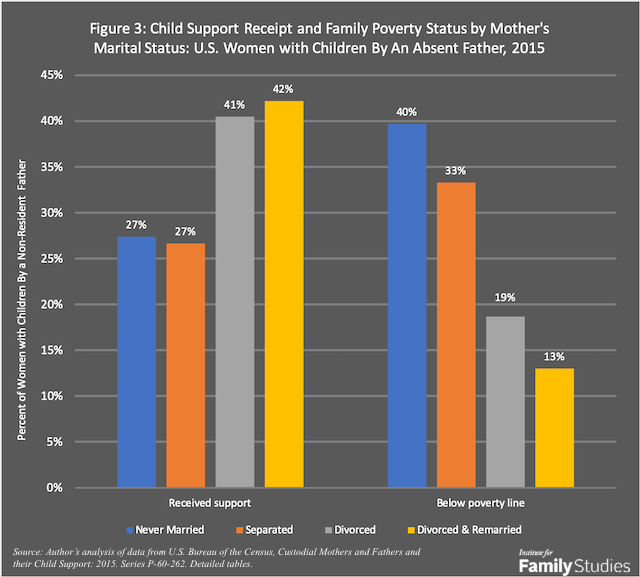

During this time period, never-married mothers were less likely than divorced mothers to receive child support payments from the non-resident fathers of their children, as shown in Figure 3. For example, 27% of never-married mothers received support payments in 2015, as opposed to 41% of divorced mothers. Never-married mothers and their children were more likely to be surviving on incomes below the poverty line. In 2015, 40% of never-married mothers had poverty-level incomes, versus 19% of divorced mothers.

Taxpayers Provide Where Absent Fathers Do Not

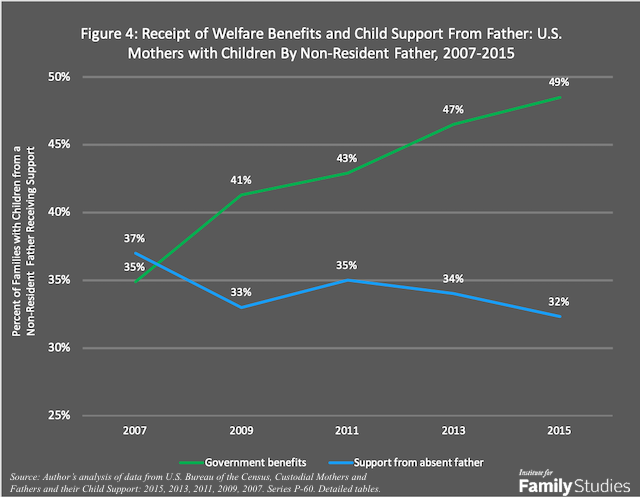

While child support agreements and payments are declining, more children of unmarried parents are receiving assistance from government nutrition, health, and welfare programs, such as SNAP (food stamps), Medicaid, WIC, CHIP, public housing, TANF, and state-run family assistance programs. The proportion of fatherless families receiving one or more of these benefits increased dramatically, rising from 35% in 2007 to 49% in 2015. (See Figure 4.) Most of the increase came through Obama-era legislation and regulatory changes that broadened the coverage of food stamp and Medicaid programs. Comparatively few families received cash welfare payments.

The surest way out of destitution for fatherless families is not through government benefits, however, but through maternal employment. When custodial mothers worked full-time, all year, only 9% of their families are in poverty. By contrast, 41% of families are poor when mothers works only part time or for only part of the year, and 63% are poor when the mother does not work at all.7 Working does not seem to act as a deterrent to fathers providing assistance, however. Mothers who work full-time were as likely or more likely to receive child support payments as mothers who do not work or work part time.8

Of course, having one’s single parent work full time means that the child receives less time and attention from his or her mother, as well as from the non-resident father. And while it may prevent hardship, a single parent’s employment is hardly likely to make the family as well off financially as it would be if both parents were available to bring in earnings or help with child care.

No Substitute For Responsible Fathers

Children do well when both parents participate actively in their upbringing and work to provide consistent attention, affection, and discipline, as well as meeting their material needs. This is easiest to achieve when the parents are married and living together. Yet, half of all young people will spend at least part of their childhoods living apart from one biological parent, usually their fathers.9 While married fathers of today are playing a more active role in their children’s lives than married fathers of yesteryear, many fathers who don’t live with their kids are doing little either to support their children or even interact with them. The trend data reviewed in this essay suggest that the situation is not improving.

State and federal programs to enforce child support by non-resident fathers (and mothers) are working mainly to the benefit of the children of single parents who have more going for them in the first place. These are college-educated women (and men) who are legally divorced and have written agreements with their former spouses concerning each parent’s rights and obligations. Government enforcement efforts are not working well for the children of often low-income single parents who have never married or have separated from their spouses without getting officially divorced.

These parents are likely to have only a high school education and little prospect of obtaining a well-paying job. They and their children are apt to be living in high-poverty, high-crime, low-resource neighborhoods replete with bad peer and adult influences. Their children are more likely than children of married parents to be in less than excellent health, have a psychological or physical health condition, be struggling or acting up in school, and engage in unprotected sexual activity or delinquent behavior as teenagers or young adults.10

Providing subsidized food and medical care to these families does not address their central problems. Social service agencies are no substitute for dedicated, loving, responsible fathers. The dual challenges for private or government-sponsored efforts to assist such children and families are to find better ways to pressure unmarried fathers to live up to their responsibilities to their offspring and discourage future generations of young men and women from stumbling into unintentional, unmarried parenthood.

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce.

1. Fathers devoted 7 hours per week to child care in 2011, compared to 2.5 hours in 1965. Mothers devoted 14 hours per week to child care in 2011. Pew Research Center analysis of American Time Use Survey data, as found here: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/03/14/modern-parenthood-roles-of-moms-and-dads-converge-as-they-balance-work-and-family/.See also: Bureau of Labor Statistics, American Time Use Survey, 2018 as found here:https://www.bls.gov/charts/american-time-use/activity-by-parent.htm

2. The U.S. Bureau of the Census produces biennial reports for the Office of Child Support Enforcement, Administration on Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, based on supplements to the Current Population Survey. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Custodial Mothers and Fathers and their Child Support: 2015, 2013, 2011, 2009, 2007. Series P-60. Detailed tables.

3. In 2015, there were a total of 22,357,000 children under age 21 in the U.S. living with 13,573 custodial parents who had children with a father or mother who did not live with them. Of these children, 8,307,000, or 37%, were in families with incomes below the official poverty line; 10,918,000 of the parents were mothers, caring for some 18 million children; and 2,655,000 were fathers caring for some 4 million children. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Custodial Mothers and Fathers and their Child Support: 2015. Series P-60-262. Tables 10 & 11.

4. The percentages cited represent the number of custodial mothers receiving child support as a fraction of all custodial mothers. The Office of Child Support Enforcement and the Census Bureau calculate the percentage differently: as a fraction of those mothers who were awarded child support and supposed to receive it in the given year. Reckoned this way, 71% of mothers who were supposed to receive support in 2015 received some payments and 45% received the full amount owed. My position is that all custodial mothers should be receiving regular support from the non-resident fathers; hence, the lower numbers.

5. When the mother was the non-resident parent, the proportion who had not seen their child in a year was 30% in 2015.

6. A 60% majority of custodial mothers received some form of non-cash support from the non-resident fathers in 2015. The most common forms were a birthday, holiday, or other gift (57%); clothes, diapers, shoes, etc., (45%); and food or groceries (33%).

7. In 2015, 50% of custodial mothers worked full-time, full year; 30% worked part-time or for part of the year; and 20% did not work all year.

8. In 2015, 33% of mothers who worked full-time received child support payments, as did 33% of mothers who worked part-time and 31% of those who did not work. In 2013, however, 37% of mothers who worked full-time received child support payments, as did 34% of mothers who worked part-time and 27% of those who did not work.

9. Nicholas Zill and W. Bradford Wilcox, “1 in 2: A new estimate of the share of children being raised by married parents,” Institute for Family Studies Blog, 2/27/2018.

10. Sara McLanahan, and Gary Sandefur, Growing Up with A Single Parent(1994). Anna Égalité, How Family Background Influences Student Achievement. Education Next, 16, No. 2, (Spring 2016). Zill, N. (1996). “Family Change and Student Achievement: What We Have Learned, What It Means for Schools,” in Family-School Links: How Do They Affect Educational Outcomes?ed. Alan Booth and Judith F. Dunn. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1996.Amato, P.R. & Booth, A. (1997). A generation at risk: Growing up in an era of family upheaval. Harvard University Press. Amato, P.R. & Gilbreth, J.G. (1999). Nonresident fathers and children’s well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family 61 (August 1999): 557-573.