Highlights

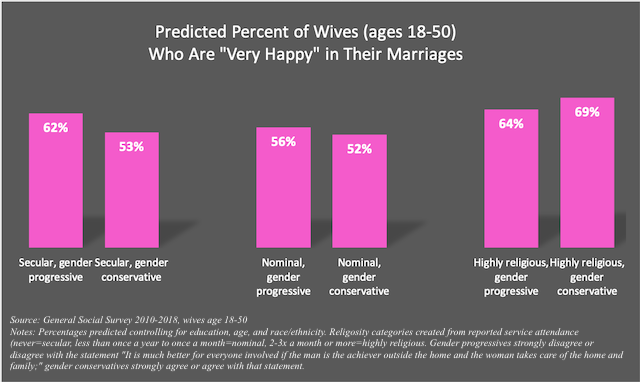

- A look at the General Social Survey (2010-2018) shows a similar curve in the relationship between religion, gender ideology, and wives’ reports of being “very happy” in their marriages. Post This

- The J-Curve is really about the fascinating interaction between religion and gender ideology when it comes to the quality of women’s relationships. Post This

There is a “J-Curve” in relationship quality for women. As we noted in The New York Times:

When it comes to relationship quality, there is a J-curve in women’s marital happiness, with women on the left and the right enjoying higher quality marriages than those in the middle — but especially wives on the right.

Our new report, The Ties that Bind, measured relationship quality with a four-item index from the Global Family and Gender Survey (GFGS) tapping women’s overall satisfaction, closeness, commitment, and perceived stability of the relationship. On this index, we find that secular progressive women on the Left do comparatively well, women in the religious middle and especially secular, conservative women do poorly, and religious, conservative women on the Right do best, followed closely by religious, progressive women.

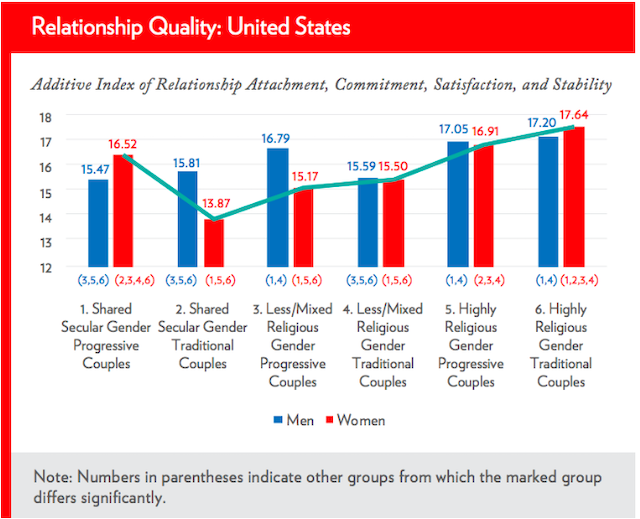

Some critics thought the primary focus of the report and our Op-ed in The Times was political ideology. Not so. Look closely at this figure from The Ties That Bind on relationship quality in the United States:

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institution Global Family and Gender Survey (2018)

Clearly, the J-Curve is based primarily on the interaction between religion and gender ideology in ordinary women’s lives. It is approximated somewhat when you look at political ideology, a point we noted in The Times, insofar as women on the political Left and political Right also tend to report higher quality marriages. But the J-Curve is really about the fascinating interaction between religion and gender ideology when it comes to the quality of women’s relationships.

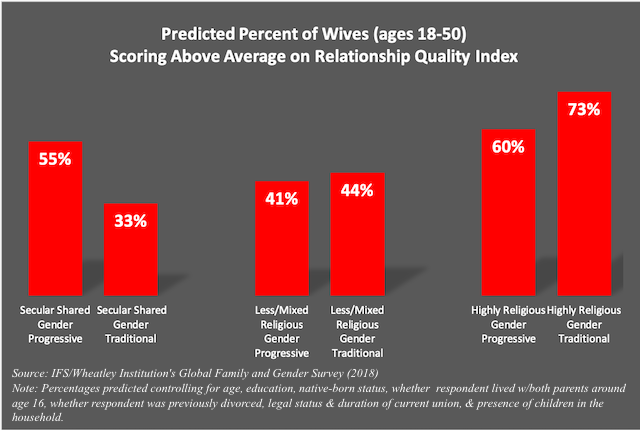

Note, for instance, that women with conservative gender attitudes (who believe that “It is usually better for everyone involved if the father takes the lead in working outside the home and the mother takes the lead in caring for the home and family”) who never attend church do the worst,whereas women with conservative gender attitudes who attend church with their husbands do the best. Our results here parallel findings from sociologists Samuel Perry and Andrew Whitehead, who report that religion can moderate “the ways gender ideology influences heterosexual relationship outcomes,” especially for women. Indeed, when we focus on the share of U.S. wives with above-average relationship quality, this is what we find:

Secular progressive wives do comparatively well on this index, with 55% predicted to have higher quality relationships. Less than 50% of the wives who are nominally religious or in mixed-religious marriages (where the spouses do not attend together) can be expected to be found in such relationships. Secular, conservative wives are the least likely to have high-quality relationships, with only 33% of them expected to show up in the top half. Finally, wives who share religious attendance with their husbands are more likely to have higher quality marriages, with religious, conservative wives reporting the highest quality marriages. Specifically, 73% of them score above average on the relationship quality index (net of controls).

But is the Global Family and Gender Survey (GFGS) representative of American wives in general? Does this J-Curve hold up in other surveys of American women? Can it be replicated? Yes, it can.

A look at the General Social Survey (2010-2018) shows a similar curve in the relationship between religion, gender ideology, and wives’ reports of being “very happy” in their marriages. The J-Curve in the GSS is not as pronounced as the one in the GFGS, but we attribute this to the fact that the GSS does not allow us to measure joint religious attendance in the last decade. Couples who attend church together are markedly happier than those who do not. In any case, look at this J-Curve in women’s marital happiness in the GSS when we look at the interaction between religion and gender ideology:

Again, the GSS indicates that secular progressive wives are likely to be “very happy” in their marriages, with wives in the religious middle being less happy along with secular conservative wives, and religious conservative wives being the happiest. The data from the GSS, then, also suggests that there is a J-Curve in women’s marital happiness.

Why is it that secular progressive and religious wives, especially religiously-conservative wives, report higher-quality marriages? This is the question we took up in The Times. Our answer boils down to two points:

- Religious wives benefit from “the social, emotional and practical support for family life provided by a church, mosque or synagogue”; and,

- Secular progressive wives and religious conservative wives both benefit from “devoted family men. Both feminism and faith give family men a clear code: They are supposed to play a big role in their kids’ lives. Devoted dads are de rigueur in these two communities. And it shows: Both culturally progressive and religiously conservative fathers report high levels of paternal engagement.”

In other words, for secular wives, devoted family men + progressive gender ideology = happy marriages. For religious wives, devoted family men + religious community = happy marriages, regardless of gender ideology.

W. Bradford Wilcox is professor of sociology at the University of Virginia and senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. Laurie DeRose is a Research Assistant Professor at the Maryland Population Research Center at the University of Maryland at College Park, a senior fellow with the Institute for Family Studies, and Director of Research for the World Family Map project. Jason S. Carroll, Ph.D., is a professor in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University and the Associate Director of the Wheatley Institution.