Highlights

- The family divide in America matters because the American Dream is in much better shape when marriage anchors the lives of children —and the communities they grow up in. Post This

- The good news: less divorce and less nonmarital childbearing. The bad news: the nation still remains deeply divided when it comes to family structure and stability. Post This

- 5 ways to strengthen US family life: end the marriage penalty, strengthen career and tech education, subsidize lower-income work, expand the child tax credit, and launch a public service campaign on the success sequence. Post This

Editor’s Note: The following essay is an edited and abridged version of IFS senior fellow W. Bradford Wilcox's testimony before the U.S. Senate Joint Economic Committee's Hearing: "Improving Family Stability for the Well-Being of Children," which was held on February 25, 2020. Dr. Wilcox's full testimony is available here.

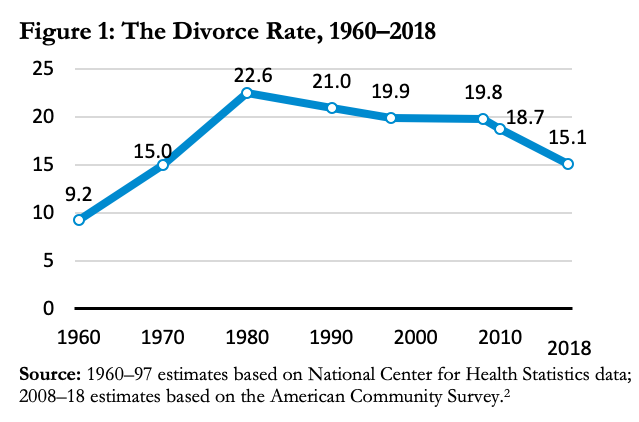

There is both good news and bad news to report about marriage and family life in America. The good news, as Figure 1 indicates, is: divorce is down dramatically since 1980. This means the fabled statistic—that one-in-two marriages end in divorce—is no longer true. What’s more, nonmarital childbearing has also reversed course since the Great Recession.

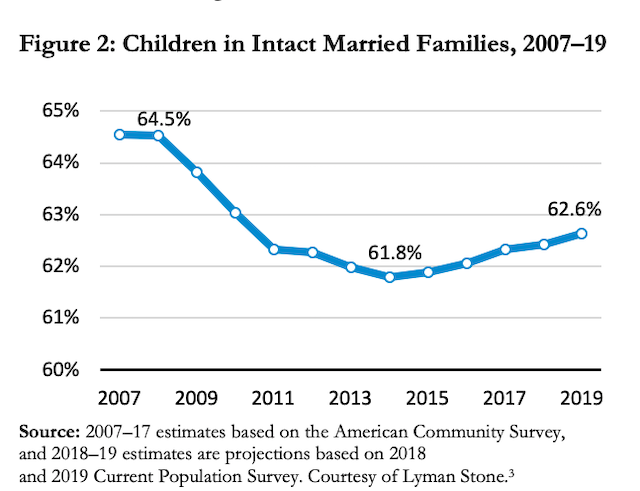

Less divorce and less nonmarital childbearing equal more children being raised in intact, married families, as Figure 2 shows us.

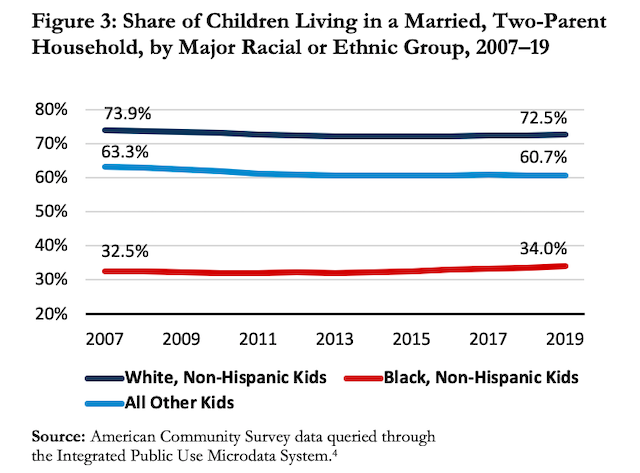

Note also that this uptick in children being raised by their own married parents has been strongest for black children, as we see in Figure 3. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that the nation still remains deeply divided when it comes to family structure and stability. Single parenthood is about twice as high for children from families with less education and for black children.1 This form of family inequality leaves many working-class and poor children “doubly disadvantaged”—navigating life with less money and an absent parent.2

The Roots of Family Inequality

This family inequality is rooted in shifts in our economy, culture, and public policy.3 We know, for instance, that men without college degrees have seen their spells of unemployment climb in recent years,4 undercutting their marriageability.5 Since the 1960s, American culture has de-emphasized the values and virtues that sustain strong and stable marriages in the name of “expressive individualism.”6 But what is interesting about this well-known cultural trend is that a cultural countercurrent has quietly emerged in recent years among elite Americans. While America’s educated elite overwhelmingly reject a renewed marriage-centered ethos in public, they embrace a marriage-centered ethos for themselves and their children in private, thereby affording their families a significant cultural advantage when it comes to forging a strong and stable family life.7 Unfortunately, this marriage-minded ethos has not yet caught on as much in less-advantaged communities.8

Likewise, declines in religious and secular civic engagement have been concentrated among working-class and poor Americans, robbing these families of the social support they need to thrive and endure.9 Finally, means-tested programs from the federal government often penalize marriage among lower-income families.10

Why Family Structure and Stability Matter

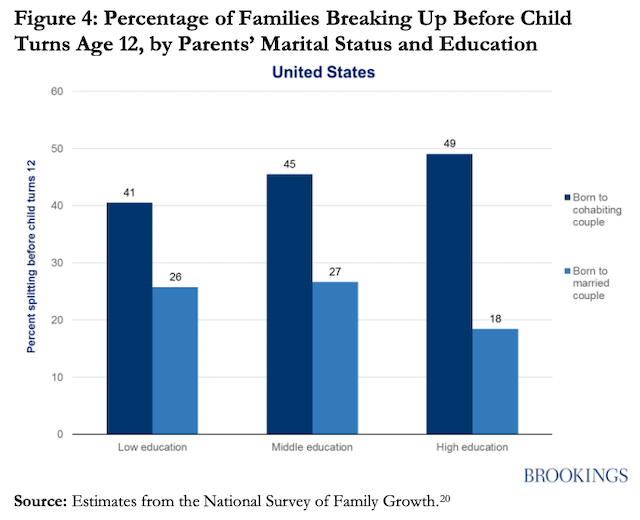

The family divide in America matters because the American Dream is in much better shape when marriage anchors the lives of children — and the communities they grow up in. My use of the term “marriage” here is deliberate. No family arrangement besides marriage affords children as much stability as does this institution, as Figure 4 shows us.

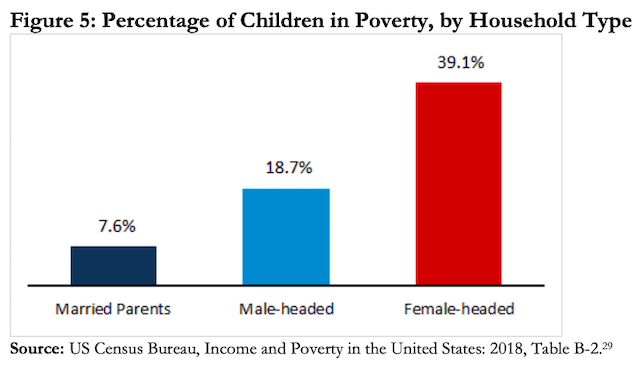

It is impossible to summarize here the voluminous literature on family and child well-being but suffice it to say that children are much more likely to thrive in school11 and steer clear of poverty when their parents are married.12 Figure 5 is telling on this score.

Family structure also matters for communities. Scholarship by Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues indicates that neighborhoods with more two-parent families are significantly more likely to foster rags-to-riches mobility for poor children.13 In all these ways, the research tells us that the American Dream is much stronger in communities with more married families—communities like the ones the chairman and vice-chair hail from.

What’s to Be Done

Unfortunately, many communities today don’t have the family stability found in Alpine, Utah or Old Town Alexandria, Virginia. So, what should we do to renew marriage in communities where families are more fragile?

1. End the Marriage Penalty in Means-Tested Programs. Currently, marriage penalties in programs such as Medicaid, SNAP, and the EITC can reach as high as 32% of total household income.14 This is unconscionable. Congress should eliminate marriage penalties by doubling income thresholds for programs serving low-income married families with children under age 6.

2. Strengthen Career and Technical Education. Most young adults will not get a 4-year college degree, yet our education system devotes far too little attention to this group. We need to scale up career and technical education15 to boost the earnings, self-confidence, and marital prospects of young men and women who are not on the college track.16 One promising provision already under consideration in Congress is Workforce Pell — which would make Pell Grants available to shorter, job-focused community college programs that lead to industry-recognized credentials.17

3. Subsidize Lower-Income Work. To strengthen the economic foundations of poor and working-class family life and to increase the returns of work for less-educated men and women, the federal government should subsidize lower-income work.18 A wage subsidy would reinforce the value of work and also send a powerful signal to working-class families that the nation stands with them. One approach would set the value of the subsidy relative to a “target wage” of $15 per hour and “would close half the gap between the market wage and the target” wage.19 Unlike the EITC, this wage subsidy would be added to worker’s paychecks, providing them with an ongoing, paycheck-to-paycheck boost to their family budget.

4. Expand the Child Tax Credit. To help families cover the expenses of raising young children and reduce the financial stresses that can cause marital instability, Congress should expand the child tax credit to $3,000 per child and extend it to payroll tax liabilities or provide families with a fully refundable credit.20 The credit should be paid out on a monthly basis to give families month-to-month support in addressing the financial challenges of raising a family today.21 To limit the expense, this expansion should be limited to children under age 6.

5. Launch Civic Efforts to Strengthen Marriage. I would like to see a campaign organized around what Brookings Institution scholars Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill have called the “success sequence,” in which young adults are encouraged to pursue education, work, marriage, and parenthood in that order.22 Ninety-seven percent of young adults today who have followed this sequence are not poor.23 A campaign organized around this sequence could meet with the same success as the recent national campaign to prevent teen pregnancy.24

Measures like these are necessary to bridge the divide in family structure and stability across the U.S., a divide I think we can all agree is unacceptable and un-American.

1. W. Bradford Wilcox, Jeffrey P. Dew, and Betsy VanDenBerghe, 2019 State of Our Unions: iFidelity: Interactive Technology and Relationship Faithfulness(Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project, Wheatley Institution, and Brigham Young University, School of Family Life,2019).

2. Sara McLanahan, “Diverging Desitinies: How Children Are Faring Under the Second Demographic Transition,” Demography41, no.4 (2004): 607–27.

3. Andrew J. Cherlin, The Marriage-Go-Round (New York: Random House, 2009); David Ellwood and Christopher Jencks, “The Uneven Spread of Single-Parent Families: What Do We Know? Where Do We Look for Answers?,” in Social Inequality, ed. Kathryn Neckerman (New York: Russell Sage, 2004); W. Bradford Wilcox, Nicholas H. Wolfinger, and Charles E. Stokes, “One Nation, Divided: Culture, Civic Institutions, and the Marriage Divide,” Future of Children 25, no. 2 (2015); and William J. Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Under Class, and Public Policy(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

4. David Autor and Melanie Wasserman, “Wayward Sons: The Emerging Gender Gap in Labor Markets and Economics,” Third Way and NEXT, 2013; Nicholas Eberstadt, Men Without Work(West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press, 2016); and Oren Cass et. al, “Work, Skills, Community: Restoring Opportunity for the Working Class,” Opportunity American, Brookings Institution, and American Enterprise Institute, November 27, 2018.

5. Alexandra Killewald, “Money, Work, and Marital Stability: Assessing Change in the Gendered Determinants of Divorce,” American Sociological Review 81, no. 4 (2016): 696–719; and Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged.

6. Cherlin, The Marriage-Go-Round, 226–29; W. Bradford Wilcox and Elizabeth Marquardt, “State of Our Unions 2010: When Marriage Disappears: The New Middle America,” National Marriage Project, 2010.

7. Wendy Wang and W. Bradford Wilcox, “State of Contradiction: Progressive Family Culture, Traditional Family Values in California,” Institute for Family Studies, January 14, 2020; and Wilcox and Marquardt, “State of Our Unions 2010.”

8. Wang and Wilcox, “State of Contradiction.”; and Wilcox, Wolfinger, and Stokes, “One Nation, Divided.”

9. Robert D. Putnam, Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015); and Wilcox, Wolfinger, and Stokes, “One Nation, Divided.”

10. Adam Carasso and C. Eugene Steuerle, “The Hefty Penalty on Marriage Facing Many Households with Children,” Future Children15, no. 2 (2005): 157–75; W. Bradford Wilcox, Joseph Price, and Angela Rachidi, “Marriage, Penalized: Does Social-Policy Affect Family Formation?,” American Enterprise Institute and Institute for Family Studies, July 26, 2016; W. Bradford Wilcox, Chris Gersten, Jerry Regier, “Marriage Penalties I Means-Tested Tax and Transfer Programs: Issues and Options,” US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Family Assistance, January 20, 2020.

11. Kathryn Harker Tillman, “Family Structure Pathways and Academic Disadvantage Among Adolescents in Stepfamilies,” Sociological Inquiry 77, no. 3 (2007): 383–424. See also: David Autor et. al, “School Quality and the Gender Gap in Educational Achievement," American Economic Review106, no. 5 (2016): 289–95; Melissa S. Kearney and Phillip B. Levine, “The Economics of Non-Marital Childbearing and the ‘Marriage Premium for Children,’” (working paper, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2017); Robert I. Lerman and W. Bradford Wilcox, “For Richer, for Poorer: How Family Structures Economic Success in America,” American Enterprise Institute and Institute for FamilyStudies, 2014; and Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur, Growing Up with a Single Parent. What Hurts, What Helps(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994). See also: Donna J. Ginther and Robert A. Pollack, “Does Family Structure Affect Children's Educational Outcomes?” (working paper, FRB Atlanta, Georgia, 2001); Kearney and Levine, ‘The Economics of Non-Marital Childbearing and the ‘Marriage Premium for Children.’”; and Roger A. Wotjkiewz and Melissa Holtzmann, “Family Structure and College Graduation: Is the Stepparent Effect More Negative than the Single Parent Effect?,” Sociological Spectrum 31, no. 4 (2011): 498–521.

12. Robert I. Lerman, Joseph Price, and W. Bradford Wilcox, “Family Structure and Economic Success Across the Life Course,” Marriage & Family Review 53, no. 8 (2017): 744–58; and Robert I. Lerman, “Marriage and Economic Well-Being of Families with Children: A Review of the Literature,” Urban Institute, July 1, 2002.

13. Raj Chetty et. al, “Where Is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no. 4 (2014): 1553–1623.

14. Douglas Besharov and Neil Gilbert. 2015. Wilcox, Gersten, and Regier, “Marriage Penalties I Means-Tested Tax and Transfer Programs”; and Wilcox, Price, and Rachidi, “Marriage, Penalized.”

15. Robert Lerman, “Expanding Apprenticeship Opportunities in the United States,” Brookings Institution, June 19, 2014; Oren Cass, The Once and Future Worker(New York: Encounter Books, 2018); and Isabel Sawhill, The Forgotten Americans: An Economic Agenda for a Divided Nation (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018).

16. James J. Kemple, “Career Academies: Long-Term Impacts on Work, Education, and Transitions to Adulthood,” MRDC, June 2008.

17. Oren Cass et. al, “Work, Skills, Community.”

18. Oren Cass, The Once and Future Worker; and Sawhill, The Forgotten Americans.

19.Oren Cass, “The Case for the Wage Subsidy,” National Review, November 16, 2018.

20. Amber and David Lapp, “Work-Family Policy in Trump’s America,” Family Studies, December, 2016; Josh McCabe, “A Pro-Family Child Tax Credit for the U.S.,” Family Studies November 18, 2015; Lyman Stone, “Cash for Kids?” Family Studies, March 12, 2019.

21. Amber and David Lapp, “Work-Family Policy in Trump’s America,” Family Studies, December, 2016; Josh McCabe, “A Pro-Family Child Tax Credit for the U.S.,” Family Studies November 18, 2015; Lyman Stone, “Cash for Kids?” Family Studies, March 12, 2019.

22. Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill, Opportunity Society (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2009); and W. Bradford Wilcox and Wendy Wang, “The Millennial Success Sequence: Marriage, Kids, and the ‘Success Sequence’ Among Young Adults,” American Enterprise Institute and Institute for Family Studies, June 14, 2017.

23. Wilcox and Wang, “The Millennial Success Sequence.”

24. Melissa Kearney and Phillip Levine, “Media Influences on Social Outcomes: The Impact of MTV's 16 and Pregnant on Teen Childbearing,” (working paper, National Bureau for Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2014); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics Reports, “Births: Final Data for 2015,” December 23, 2015; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics Reports, “Births: Final Data for 2016,” December 2016; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Natality Public-Use Data 2007–2017 [data set].”