Highlights

- Divorce does seem to increase the likelihood a respondent will believe whites suffer discrimination and the likelihood that a white person will agree with all three of the basic premises of white identity politics. Post This

- Update: About 6% of all white respondents in the 2016 ANES expressed agreement with all three opinions associated with white identity politics. Post This

Editor's Note: This research brief has been updated by the author with corrected information: only about 6% of white Americans agreed with all three attitudes of white identity politics in the 2016 ANES survey (8/10/18).

A year ago, the so-called Alt-Right (short for "alternative right" and the latest manifestation of the U.S. white nationalist movement) made international headlines in its infamous "Unite the Right" rally in Charlottesville, VA. The rally led to dozens of serious injuries and the death of one counter-protester. Scholars and journalists have written much about this phenomenon, trying to discern where it came from and what it means for American democracy. The Alt-Right, and the racist Right more broadly, has proven very difficult to quantitatively and systematically study.

The Alt-Right has proven particularly challenging from an analyst's perspective because of its amorphous nature and the anonymity of most of its adherents. Most Alt-Right activity takes place on the Internet, and fear of public exposure causes most people involved in the movement to rely on pen names.

The Alt-Right as a term seems to be declining in popularity, as the movement has suffered a series of setbacks over the last year. Yet the constituency for explicit white identity politics remains, which is why it is helpful to understand the economic and demographic factors that are correlated with that ideology.

Alt-Right Core Attitudes

Studying the attitudes and demographic traits of people who self-identify with the Alt-Right or a similar ideology is a great challenge. However, if we can pinpoint the attitudes that form the basis of white identity politics, and we can reasonably expect respondents to answer questions about those attitudes honestly, we can begin discerning which people are particularly likely to find such movements appealing.

Movements like the Alt-Right are correctly classified as racist. However, there are elements to these kinds of movements beyond simple racial animus, anxiety, or resentment. Although the racist right can be ideologically diverse and make many different arguments, there are three key sentiments that are widely shared across these movements: 1) a strong sense of white identity, 2) a belief in the importance of white solidarity, and 3) a sense of white victimization. Although someone who rates high on all of these views may not necessarily identify with the Alt-Right or a similar movement, we can anticipate all or nearly all individuals who are involved in white identity politics to share these attitudes.

The 2016 American National Election Survey (ANES), which was conducted over several waves during Donald Trump's campaign for the presidency, included several helpful questions on racial attitudes. Some of these were new additions to the survey. Respondents were asked how important their race was to their identity on a five-point scale ranging from "not at all important" to "extremely important." They were also asked a question measuring their feelings of white solidarity: "How important is it that whites work together to change laws that are unfair to whites?" This followed the same five-point scale. Finally, we can assess survey respondents' feelings of white victimization from their answers to the question of how much discrimination whites face in the U.S., also on a five-point scale, ranging from "none at all" to a "great deal."

To simplify the analysis, I transformed each of these questions into dichotomous variables. On the question of identity, I divided those who thought being white was "very" or "extremely important" to their identity from those who felt it was less important. I similarly divided respondents on the question of white solidarity into two groups. Finally, I divided respondents into two groups: 1) those who thought whites suffered a moderate amount of discrimination or more, and 2) those who thought they suffered none or a little.

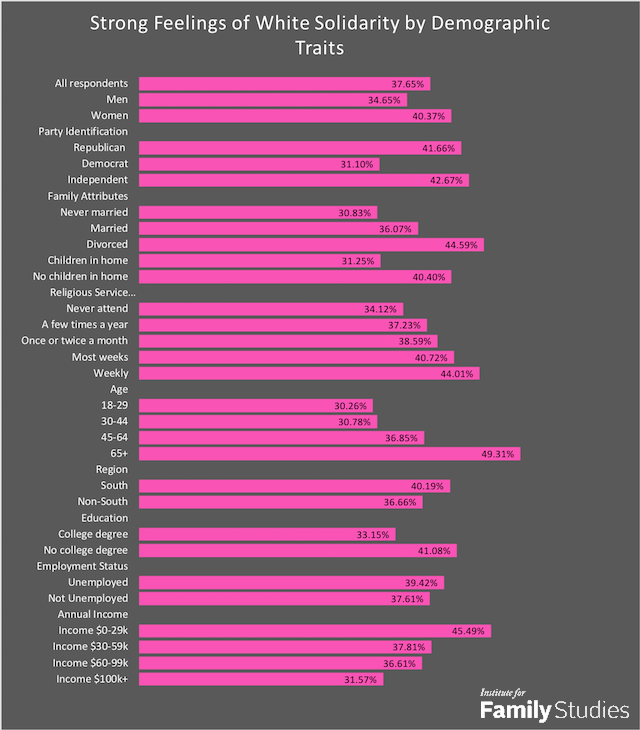

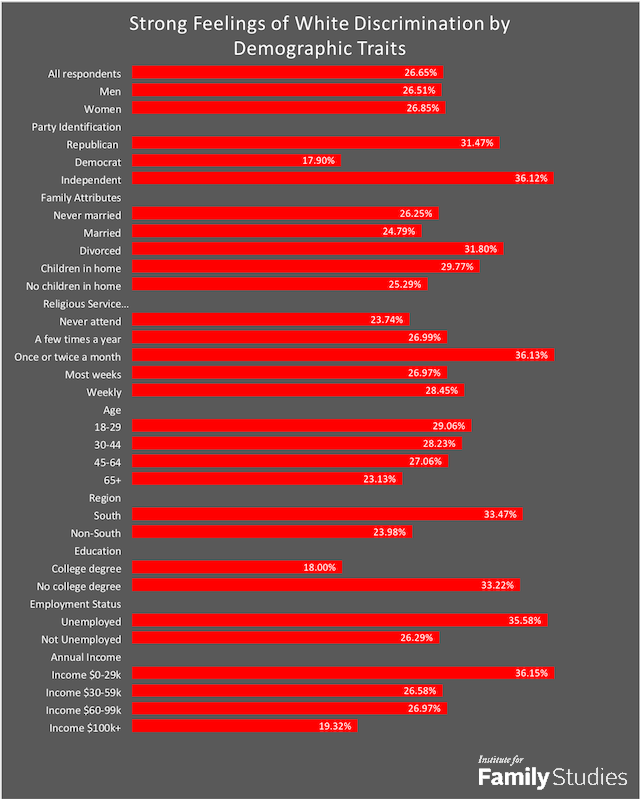

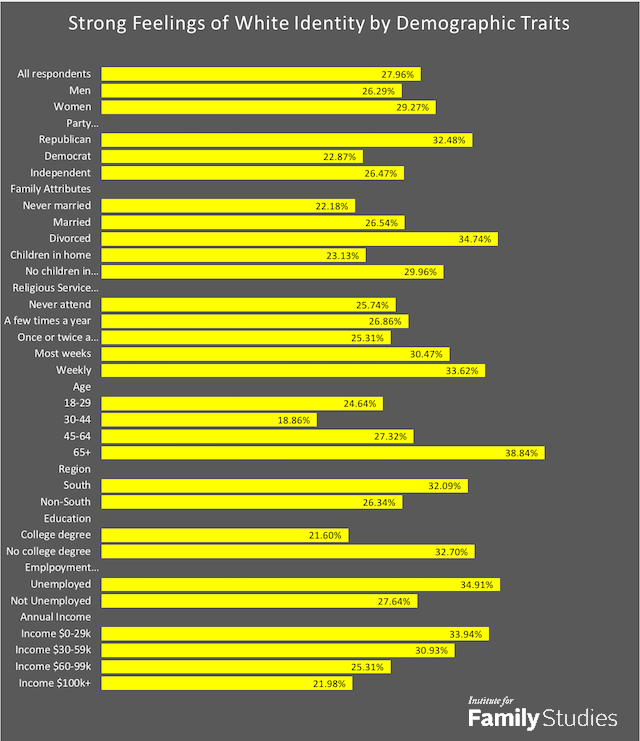

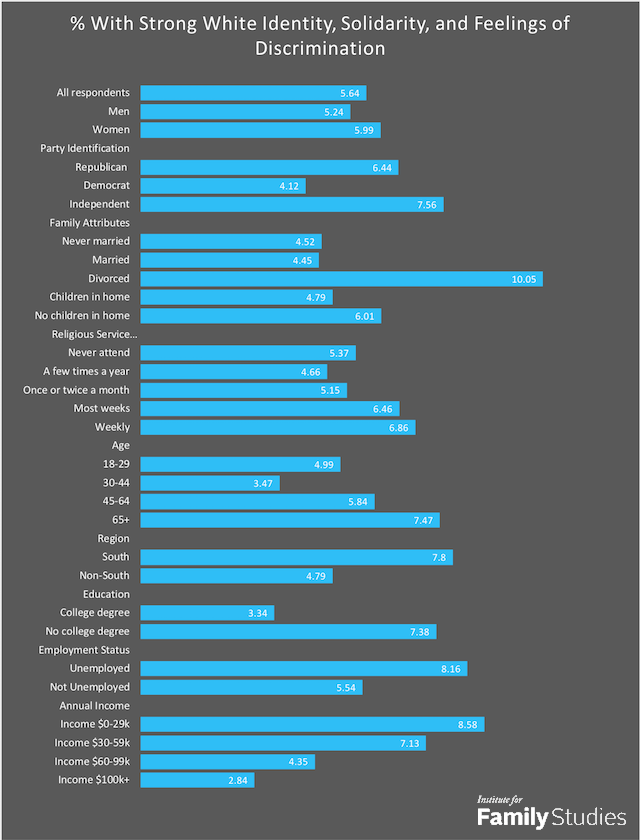

The survey included 3,038 non-Hispanic white respondents. Among these respondents, only a minority expressed high values on any of the above questions: about 28% expressed strong feelings of white identity; about 38% expressed strong feelings of white solidarity; and about 27% felt that whites suffer a meaningful amount of discrimination in American life. A much smaller minority, about 6% of respondents, expressed all three opinions. It is worth noting that a 2017Washington Post-ABC News poll estimated that about 10% of respondents supported the Alt-Right.

Although these numbers suggest we can be confident that the Alt-Right and related movements have a low ceiling of possible support, it is helpful to disaggregate the non-Hispanic white population and examine the views of various smaller groups. Over the last year, we have heard much speculation about what kind of people are drawn to the far right. Most work on this subject has been qualitative, based on personal interviews or the analysis of online material.

Do Changing Social Norms Fuel Right-Wing Radicalism?

Some observers have suggested that the contemporary far right is different from its ideological predecessors—that it is younger and more technologically competent, for example. Its leadership also appears to be less religious and socially conservative than earlier far right movements-though parts of the white nationalist movement have always expressed antipathy toward Christianity and other organized religions.

Some have also suggested that changing social norms, especially as they relate to marriage and sexuality, may be fueling the resentments that lead people into the extreme right. The rhetorical overlap between the Alt-Right and the so-called "Men's Rights Movement" and other anti-feminist movements is obvious. In her book on the Alt-Right, Kill All Normies, Angela Nagle suggests that the decline of traditional monogamous marriage and the rise of a new kind of sexual hierarchy was leading some young men to embrace political radicalism:

Sexual patterns that have emerged because of the decline of monogamy have seen a greater level of sexual choice for an elite of men and a growing celibacy among a large male population at the bottom of the pecking order. Their own anxiety and anger about their low-ranking status in this hierarchy is precisely what has produced their hardline rhetoric about asserting hierarchy in the world politically when it comes to women and non-whites.

Key Findings

Based on the far right's rhetoric on its own forums and on social media, Nagle's hypothesis seems plausible. Yet to my knowledge, the decline of traditional marriage and the apparent increase of far-right sentiments has yet to be demonstrated quantitatively. For all three of these ANES variables, the descriptive statistics show that these attitudes differed, on average, according to marital and parental status. However, the relationship was not consistent across questions. On average, married respondents expressed slightly higher levels of white identity than unmarried respondents. We see a similar but stronger pattern on the question of white solidarity, but the reverse on the question of white discrimination.

The gaps between the married and the never-married respondents on these questions do not provide compelling evidence that the breakdown of traditional family norms is leading to a new interest in right-wing radicalism. However, the results for divorce are more interesting. On every one of these questions mentioned earlier, divorced respondents were consistently one of the highest scoring groups. This may seem curious, as there is not an obvious connection between being divorced and feelings about race. It is possible that the experience of divorce makes one feel more alienated and negative in general. It is also conceivable that the causal connection is reversed, or that having these attitudes makes one more likely to get divorced.

The effect of having children in the home was inconsistent across questions. On average, respondents with children were much less likely to express strong feelings of white identity and solidarity, but somewhat more likely to say whites suffer discrimination.

One might also speculate whether there is a relationship between religious practices and racial sentiments. Traditional religious beliefs and activities are often associated with reactionary views on social issues. On the other hand, most major religious groups in the United States promote an explicitly egalitarian worldview that stresses the equal dignity of all persons, and all are officially anti-racist. When we break down respondents according to the frequency they attend religious services, the general pattern is that respondents who never attend services expressed lower scores on these questions than those who did attend, suggesting that rising secularism is not to blame for any far Right resurgence we may be seeing. These differences were not large, however, and among those that do attend religious services, there was not always a clear pattern when it came to frequency of worship and racial attitudes.

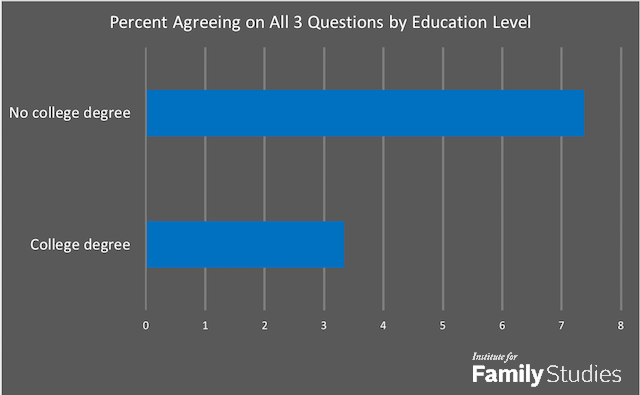

These data indicate that socioeconomic status is a substantively important predictor of how a white person will answer these questions. On each question, there was a significant gap between respondents with a college degree and those without them.

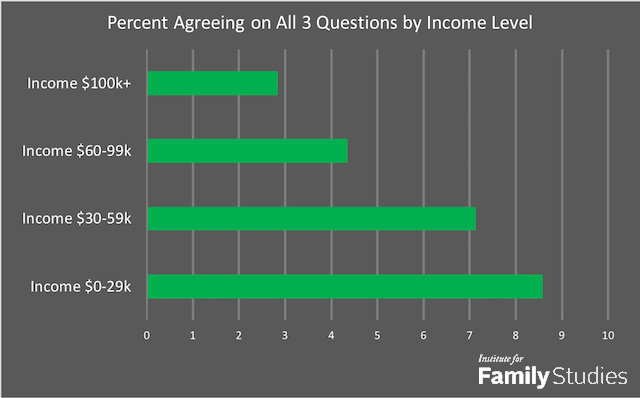

We similarly see that unemployment and lower incomes are associated with much stronger feelings of white identity, solidarity, and discrimination (see below for income).

It is additionally worth noting that there is not a large gender gap on these questions. Although the ranks of radical right movements tend to be overwhelmingly male, men are not more likely than women to possess these kinds of feelings about race. In fact, on each question, a slightly higher percentage of women expressed these attitudes.

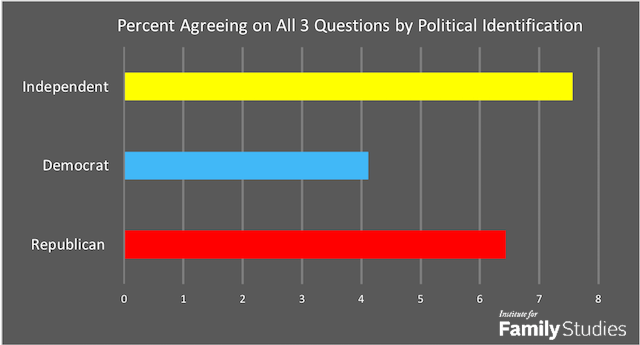

Given the long partisan divide on questions about racial policy, it is unsurprising that we see a significant gap between white Democrats and white Republicans on all of these questions related to white identity politics. It is notable, however, that the difference between Republicans and Independents was small; in fact, a greater percentage of Independents than Republicans expressed strong feelings of white solidarity and discrimination (the figure below shows the partisan divide on all three questions combined).

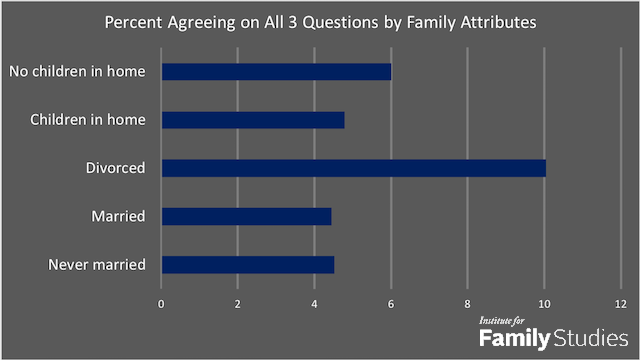

As mentioned, scoring high on any one of these measures is not necessarily an indicator that a white person would be attracted to explicit white identity politics. Thus, we should pay special attention to people who expressed high levels of white identity, solidarity, and grievance. The following figure shows the breakdown of the white respondents who expressed agreement for all three crucial elements of white identity politics.

One thing worth immediately noting is that we do not see a large percentage of whites expressing consistent support for these ideas. Divorced respondents were the only group that broke 10%. We see that white Democrats are very unlikely to express these attitudes, as are those with college degrees and very high incomes. The lack of an obvious age gap is notable. The youngest cohort differs relatively little from the oldest. This suggests that the problem of white identity politics is not something that will be resolved by generational replacement. However, this also challenges the Alt-Right's claim that the youngest whites are becoming increasingly receptive to their ideas.

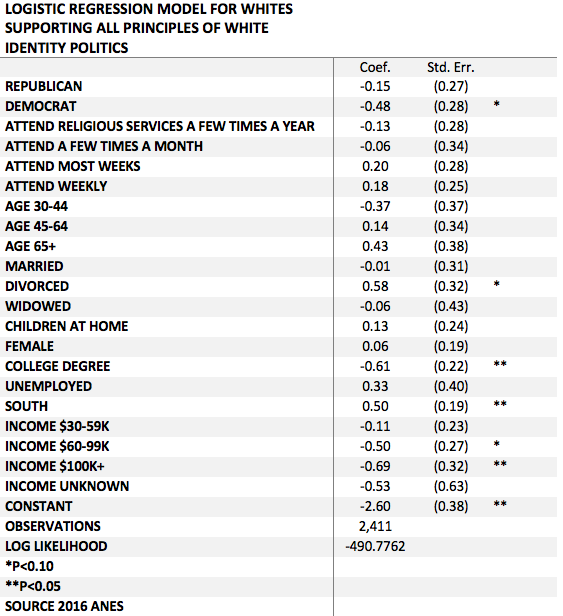

A problem with drawing any conclusions from these percentages is that many of these demographic attributes are correlated with each other. Thus, some of these apparent relationships may be spurious. To get around this problem, I created a logistic regression model for whether a respondent scored high on all three of the questions. Such models allow us to isolate the effects of each independent variable.

The regression table above indicates that religiosity and family formation are much less significant than economic variables in each of these models. Religious observance was statically insignificant. Having children was also insignificant. Marital status achieved statistical significance at the p<0.10 level, but not at p<0.05. Divorced respondents were statistically discernable from never-married respondents at this level, though there was no discernable difference between those who were currently married and those that were never married. When the model's coefficients are transformed into odds ratios, we find that a divorced respondent was 1.79 times as likely to score high on all three questions, compared to a respondent that was never married.

Conclusion

These data indicate that there is no single measure that can predict which white Americans will have the attitudes that form the basis of white identity politics. However, they provide some useful insights. First, they suggest that religious practices have a negligible effect on white people's racial attitudes. The rise of secularism in the electorate will have important political implications, but its impact on race relations may be insignificant.

Second, although marriage and children appear to be important determinants of these views in the descriptive statistics, their effects dissipate once we control for other characteristics. Never-married and currently-married respondents were not significantly different from each other, but divorce does seem to increase the likelihood that the respondent will believe whites suffer discrimination and the likelihood that a white person will agree with all three of the basic premises of white identity politics. Therefore, if we wish to discourage right-wing radicalism, encouraging more marriage will likely not be effective, but strengthening marriages and discouraging marriage dissolution may be helpful.

If we wish to discourage right-wing radicalism, encouraging more marriage will likely not be effective, but strengthening marriages and discouraging marriage dissolution may be helpful.

Pundits and scholars have spent the last several years debating whether racism or economic anxiety is the main catalyst for right-wing populism and white racial identity politics. These debates were particularly heated during the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the UK's "Brexit" vote. These data add additional complexity to these questions. It turns out that economic variables are some of the stronger determinants of white attitudes on racial questions. Higher incomes are associated with lower levels of white racial identity, racial solidarity, and feelings of discrimination. A college degree is a statistically significant and substantively important variable. This suggests increased education is one of the more effective tools for combatting dangerous ideologies.

There are important caveats to these findings. As is always the case when studying survey data related to race, social desirability bias is a significant concern. That is, some respondents may not be providing their honest opinions, given the social stigma attached to racism. This is particularly problematic if the prevalence of social desirability bias differs systematically across different groups. In this case, it is possible that wealthier and better-educated respondents were simply more likely to lie about their real attitudes.

I should also reiterate that people who have a strong sense of white identity and racial grievance are not necessarily involved with radical movements. Therefore, the demographics of people who are active in the Alt-Right or related white nationalist movements may be different from what we see above. In fact, given that men are the overwhelming majority of the Alt-Right's public supporters, and women actually scored slightly higher than men on these measures, this is almost certainly the case.

A year after images from Charlottesville shocked the world, the Alt-Right remains in a weakened state. The movement hoped it would be able to transition from the Internet into the real world, becoming a normal part of American politics. That has not happened. These data further indicate that the potential constituency for the kind of politics the Alt-Right advocates is relatively small. Majorities of white Americans reject the basic premises of white identity politics, and only a small minority agree with all of them. This does not mean the radical right is not a problem that can be safely ignored. More work needs to be done, but knowing the individual characteristics associated with far-right views is a useful initial step.

George Hawley is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Alabama. His books include Demography, Culture, and the Decline of America's Christian Denominations and Making Sense of the Alt-Right.

Photo credit: Anthony Crider via Wiki Media Commons.

Appendix