Highlights

When divorce was rare and divorce laws were strict, only those with a large amount of resources could obtain a divorce, because divorcing and its aftermath were costly. A man or woman who wished to end a marriage needed the financial, social, and intellectual means to start and win a legal case. He or she needed the financial and social means to get by after the divorce. Finally, he or she needed the perseverance and social capital to endure the normative judgment against divorce and divorcées.

It was expected that the relation between divorce and resources would dwindle if divorce laws were liberalized and divorce became a normal event. Divorce would be an individual decision that would be made based solely on the quality of a union, and not on available resources.

The American sociologist William Goode, however, anticipated that as normative, legal, social, and economic barriers against divorce faded away, divorce would become more common among those with fewer resources than among the wealthy or well educated (Goode 1962, 1970, 1993). Couples in lower social classes more often face economic hardship (like unemployment or poverty), which increases the risk of divorce and break-ups, and have fewer resources, such as education and social capital, to overcome such hardship. In contrast, people in higher social classes not only have more money but also have more non-financial resources (communication skills, IQ; Dronkers, 2002) that may help them better maintain their relationships. Over the course of the twentieth century, Goode’s prediction proved largely correct on both sides of the Atlantic.

The most common way to test how resources affect divorce risk over time is to examine the relation between people’s education level—which is linked with their financial and social resources—and their divorce risk. But most studies limit themselves to one country, most often the USA.

Juho Harkönen and I analyzed the relation between educational level and divorce risk for 16 European countries and the USA, using data collected in the 1980s (Harkönen and Dronkers 2006). We found that the relation between education and divorce became more negative during the twentieth century in Flanders, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Sweden and the USA. Here, I will replicate our 2006 analysis with more up-to-date data and study not just marriage but all types of first unions (cohabitation, marriage, and cohabitation followed by marriage).

Data

As in my previous posts on this blog, I use data from the Gender and Generations Programme (GGP), a longitudinal survey of 18- to 79-year-olds in 18 European countries, completed in the first decade of this century. Again, I use the available harmonized data of GGP’s first wave, which ensure the highest level of cross-national comparability. I classify individuals into three levels of educational attainment: high (university), medium (high school), and low (less than high school).

All Unions

I start with all first unions—regardless of whether the partners ever married—because that gives the fairest comparison between countries. In some countries, such as Norway, cohabitation is normal, and given the higher union disruption risk of cohabiting couples who never marry and the selectivity of marriage (more conservative couples are more likely to marry and less likely to end a union), the growing impact of education on union dissolution risk might be underestimated when looking at married couples only.

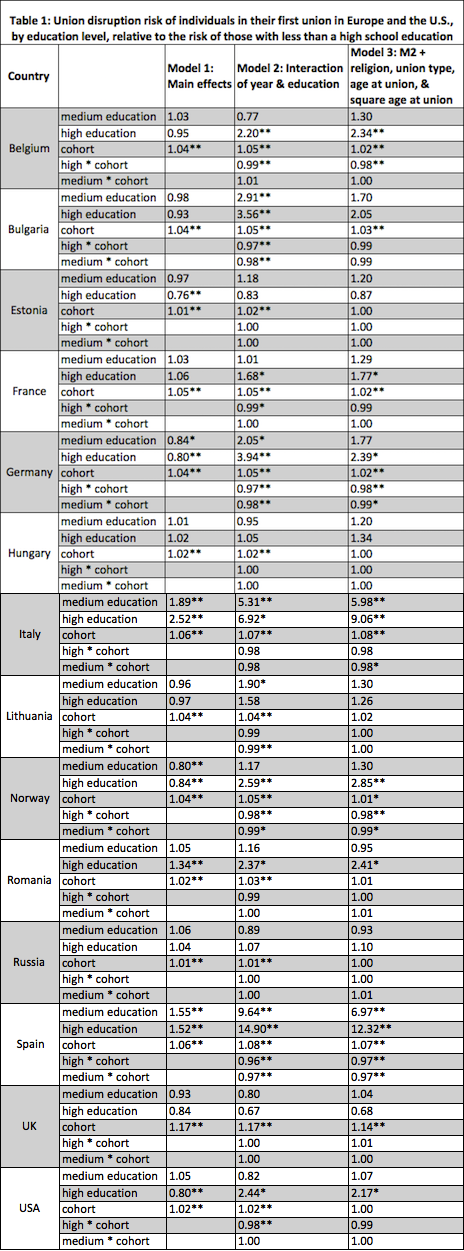

The first model in Table 1 gives the average relations between education level and union disruption from the 1940s onward. If the odds ratio is higher than 1.00, then those at the given education level dissolve their unions more often than low-education individuals (the comparison group). If the odds ratio is lower than 1.00, they exhibit less union dissolution than the least educated. In the second model, we test whether the relation between education level and union disruption changed after the 1940s. The odds ratios of the education level give these relations in the 1940s, and the odds ratios of the interactions with cohort show how these relations changed from the 1940s onwards. The third model is the same as the second model, but with other factors taken into account.

Notes: Table shows only EU member-states plus Russia and the U.S, and only first unions not ending in the death of a partner (marriage, cohabitation, or marriage followed by cohabitation). Cox regression with education level of respondent, year of union, and union duration. Weighted with a variable constructed by GGP to make the results nationally representative and account for non-response and research design. * difference in disruption risk between indicated group and the low-education group significant at p <.05; ** idem at p <.001.

In all countries, for individuals of all education levels and demographic characteristics, union dissolution has become more prevalent since the 1940s.

On average, there exists in this timeframe a positive relation between educational level and union dissolution for all first unions in Italy, Romania, and Spain. In other words, in these countries, more highly educated individuals are more likely to have dissolved their first unions. The opposite is the case in Estonia, Germany, Norway, and USA; in these nations, the average relation between education level and break-up risk in the overall timeframe is negative.

In seven countries, the link between education and union dissolution risk changed over the course of the twentieth century. Among individuals who entered their first union in the 1940s in the U.S., Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Germany, Norway, and Spain, highly educated individuals were more likely to dissolve their union than less educated couples, but in the following decades, the discrepancy changed, resulting in a higher dissolution risk for the less educated.

In another group of countries—Bulgaria, Germany, Lithuania, Norway, and Spain—moderately educated individuals were more likely than less educated people to dissolve a union begun in the 1940s, but less likely than them to do so later in the century.

The introduction of control variables, especially union type (marriage vs. cohabitation) and the age at which an individual entered his/her first union, decreases the strength of the relation between year of union and education. This decline—evident in the last column of Table 1—indicates two processes. First, highly educated individuals enter their first union later in life, and their first union is more likely to involve marriage. These facts help explain the apparent advantage of educated people in union stability. Second, the differences in union type and age at first union between education groups increased from the 1940s onward. However, even after incorporating these controls, there is still an increasing discrepancy in union dissolution risks between people of different education levels in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Norway, and Spain over the course of the twentieth century.

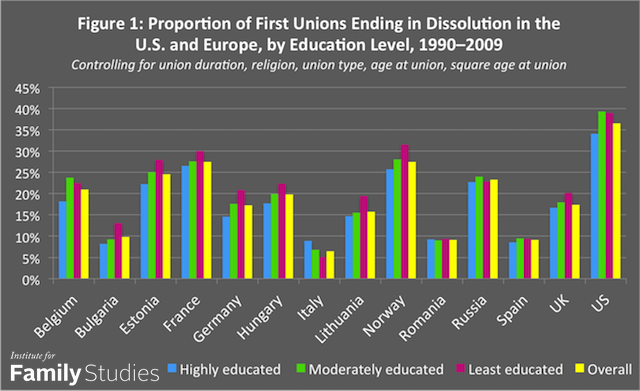

The figure below shows how union dissolution risk has varied by education level in different countries in recent years, controlling for union duration, religion, union type, age at union, and square age at union. The years, 1990-2009, indicate the period when individuals entered the union. Some of these unions may be dissolved in the future. In other words, the illustrated proportion of unions ending in dissolution understates the lifetime dissolution rates.

Only Marriages

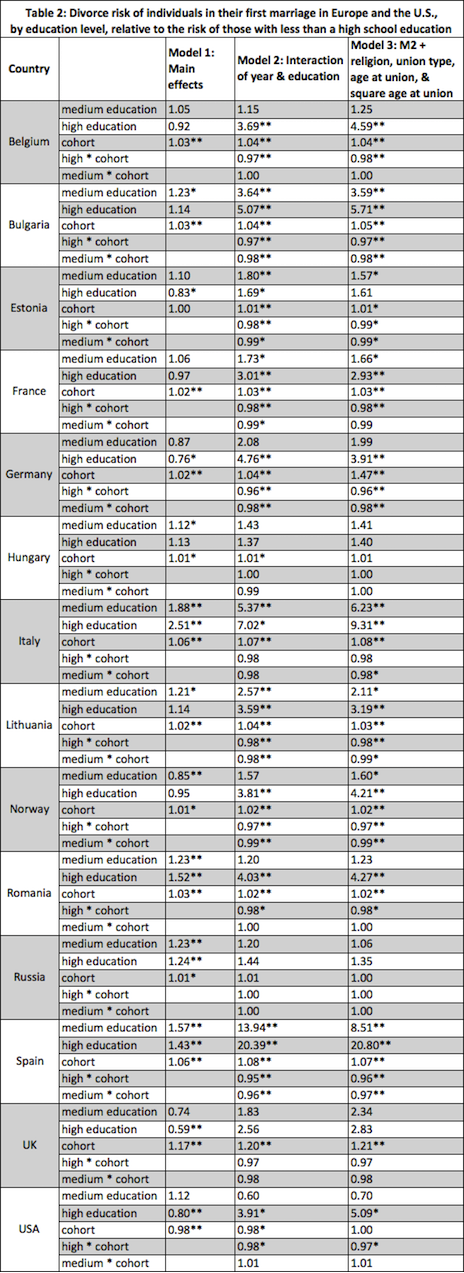

Table 2 gives the results of the same analysis as Table 1, but focusing only on those who (eventually) married their first partner.

Notes: Table shows only EU member-states plus Russia and the U.S, and only first marriages not ending in the death of a partner (marriage only or marriage followed by cohabitation). Cox regression with education level of respondent, year of union, and union duration. Weighted with a variable constructed by GGP to make the results nationally representative and account for non-response and research design. * difference in divorce risk between indicated group and the low-education group significant at p <.05; ** idem at p <.001.

In nearly all countries (Estonia is an exception), divorce became more widespread among individuals of all education levels from the 1940s onwards.

On average, the relation between education level and divorce risk in this timeframe is positive in Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Romania, Russia, and Spain, but negative in Estonia, Germany, Norway, UK, and the USA.

Divorce was more common among highly educated individuals who married in the 1930s and 1940s, but less common during the remainder of the twentieth century, in the following countries: Belgium, Bulgaria, Estonia, France, Germany, Lithuania, Norway, Romania, Spain, and the USA. In the same countries, minus Belgium, Romania, and the USA, moderately educated individuals were more likely to divorce than less educated ones in the 1930s and 1940s; however, the pattern was the reverse in the ensuing decades.

As for the analysis of all first unions, the introduction of control variables (especially age at union) decreases the strength of the relation between year of union and education, which means that better educated individuals marry at later ages and that the education-related difference in age at first union increased from the 1940s onwards. The increasing discrepancy in divorce rates between high- and low-education groups persists even after incorporating controls in Belgium, Bulgaria, Estonia, France, Germany, Lithuania, Norway, Romania, Spain, and the USA.

Conclusion

In general, highly educated individuals in the U.S. and Europe who started their union (married or cohabiting) in the ’40s dissolved their unions at higher rates than less educated people who started their union in the same period.

During the later part of the twentieth century, this relation changed drastically in many countries. The overall union dissolution rate and divorce rate increased in the USA and all European countries examined here, and at some point in the second half of the twentieth century, low-education individuals reached the same risk in union dissolution as highly educated ones.

But the dissolution rate of the least educated did not stop rising: it continued to grow faster than the average rate in many countries, while the union dissolution risk of the highly educated increased more slowly than the average rate. In some countries (Estonia, Germany, Norway, USA), the trend reversed to such an extent that the average union dissolution risk of the highly educated since the 1940s is smaller than that of the least educated. The prediction of William Goode proved to be right: at the start of the twenty-first century, the least educated couples in the U.S. and most European countries split up more often than the best educated ones.

Over the last 50 years, in summary, a new class divide between the higher and the lower classes has emerged: the risk of union dissolution or divorce. The debate about this divide is more open and aggressive on the American side of the Atlantic Ocean, as books like Charles Murray’s Coming Apart and Robert Putnam’s Our Kids attest. But the divide itself is actually larger in Europe (especially in Estonia, Germany, Norway, UK), where there is little public concern about the issue. Most European opinion-makers see union formation and dissolution as totally private issues, and social scientists tend to avoid discussing this new class divide publicly in order not to seem conservative (the worst thing which can happen to a European social scientist).

Whether we talk about the issue openly or not, however, the growing disparity in union dissolution rates affects adults and children, especially those with fewer resources to mitigate the negative consequences of union dissolution.

References

Dronkers, J., 2002. “Bestaat er een samenhang tussen echtscheiding en intelligentie?” [Is there a relation between divorce and intelligence?] Mens en Maatschappij 77:25-42.

Goode, W. J. (1962) Marital Satisfaction and Instability. A Cross-Cultural Class Analysis of Divorce Rates. In Bendix, Reinhard and Lipset, Seymour Martin (eds.) Class, Status, and Power. Social Stratification in Comparative Perspective. New York: Free Press. Pp. 377-387.

Goode, W. J. (1970) World Revolution and Family Patterns. New York: Free Press.

Goode, W. J. (1993) World Changes in Divorce Patterns. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Härkönen, J. & J. Dronkers, 2006. “Stability and Change in the Educational Gradient of Divorce. A Comparison of Seventeen Countries.” European Sociological Review 22:501-507

Murray, C. (2012). Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010 New York: Crown.

Putnam, R. D. (2015) Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Jaap Dronkers holds the chair in international comparative research on educational performance and social inequality at the Maastricht University in the Netherlands. He publishes on unequal educational attainment, changes in educational opportunities, differences between public and religious schools, achievement of migrants from different origins and destinations, effects of parental divorce, cross-national differences in divorce, and European nobility. He also participates in public debates on topics related to his research.