Highlights

- The American Dream is in rough shape in communities where marriage is rare. Post This

- Yglesias is right; too many men in America are not “marriageable,” especially in poor and working-class communities where a substantial minority are not employed in decent-paying, stable jobs. Post This

- A ‘marriage divide’ has opened up in America, but there are policies that can help to bridge it. Post This

In 1970, there was virtually no marriage divide in America. Whether rich or poor, middle class or working class, a clear majority of men and women were stably married.

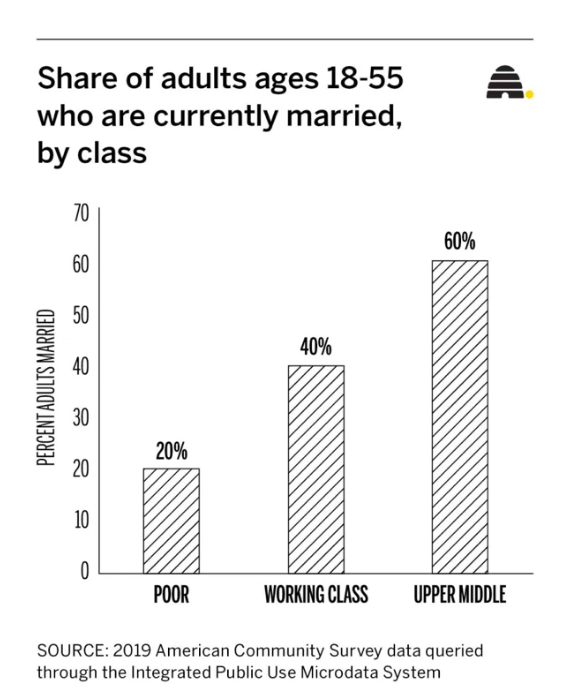

No more. A new report we published at the Social Capital Campaign spotlights a growing marriage divide that separates Americans by class and education. Of 18- to 55-year-olds, the share of those who are married from an upper-class background is 60 percent. However, this figure falls to 20% for the poor. (It is 40% for the working class.) Again, what is especially striking about this divide is that it was basically nonexistent in the 1970s.

Today, whether you consider marriage to be a cultural construct, an expression of romantic love, or a union divinely ordained, it’s still the case that most men and women in America wish to marry—and marry well. However, working-class and poor Americans are struggling to make good on this dream, with only the most educated and affluent among us having a good shot at dreams for a strong and stable family life.

America’s growing marriage divide matters because marriage is our most fundamental institution, and when marriage breaks down, our kids and communities pay a big price. Our streets are unsafer when strong families are few and far between. As Harvard sociologist Robert Sampson notes, “(f)amily structure is one of the strongest, if not the strongest, predictors of ... urban violence across cities in the United States.”

The American Dream is in rough shape in communities where marriage is rare. Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues found that, more than school quality, income inequality or race, the most predictive factor of upward mobility in a community is family structure.

And Richard Reeves at the Brookings Institution offers a telling finding: the chances of upward economic mobility differ for low-income children depending on the marital status of their parents. Four out of five children born into the bottom income quintile, but raised by married parents, had managed to escape the bottom 20% by adulthood. In contrast, those raised by a never-married single mother had only a 1 in 2 chance of doing the same.

All this suggests that marriage—our most fundamental institution—is a key engine for economic mobility and public safety in communities across America. But tragically, this institution is increasingly out of reach for millions of poor and working-class families.

Yet many on the left are skeptical that anything can be done about this marriage divide, at least from a government policy point of view. To some extent, we would agree; it’s a conservative position to recognize the limits of what government can or should do. Cultural and economic trends also play their parts. However, if the majority of young people want to establish strong, stable families, the government should do its part to bridge the gap. Marriage is not just for the elite.

The journalist Matthew Yglesias, in a recent blog post, expresses doubt that much can be done, even as he concedes that “kids are better off, on average, when raised by two parents.” However, our view is that a range of policies, many of which we set forward in “Bridging America’s Social Capital Divide,” can help poor and working-class Americans to get and stay married. Here are three sets of policies that would help.

Government Policy Should Reward, Not Penalize, Marriage

Perversely, too many of our social welfare policies, such as Medicaid and the earned income tax credit, penalize marriage among lower-income families, which is one reason there’s a marriage divide. One study found that a working-class family with two children in Arkansas stood to lose almost one-third of their real income if they married. Federal and state governments should work to reward marriage, not impede it.

This is why we also think any congressional effort to revive and expand the child tax credit should give a bonus to married parents. “Policymakers should right the wrongs of existing marriage penalties and offer a tangible validation of marriage’s value to children,” as Wilcox and Wells King recently noted in the Deseret News. “Married parents eligible for the child tax credit should also receive a 20% supplement.”

Promote the Success Sequence

Since the 1960s, American culture has de-emphasized many of the values and virtues that sustain strong and stable marriages, all in the name of “expressive individualism.” What is interesting about this well-known cultural trend is the countercurrent that has quietly emerged in recent years among the upper classes. While America’s educated elites overwhelmingly reject a marriage-centered ethos in public, they embrace it privately for themselves and their children. In this way, they afford their families a significant cultural advantage in forging a strong and stable family life.

To respond to a culture that is too often indifferent or hostile to marriage, we recommend launching a campaign centered around what Brookings scholars Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill call the “success sequence,” which refers to earning at least a high school degree, then working full time in your 20s, and then marrying before you have children.

In fact, 97% of Millennials who followed the sequence steered clear of poverty in their 30s. And, according to a new report from the American Enterprise Institute and the Institute for Family Studies, the power of the success sequence applies across class and racial lines, with more than 94% of Black and Hispanic young adults, as well as those from poor families, avoiding poverty in their 30s if they follow the sequence. If the value of the sequence became more widely known through public campaigns and high school family life curricula, this could also help bridge America’s marriage divide.

Make Men More Marriageable

Yglesias is concerned that awareness of the success sequence alone is useless if you cannot “magically conjure up husbands.” He is right; too many men in America are not “marriageable,” especially in poor and working-class communities where a substantial minority of young men are not employed in decent-paying, stable jobs. This is another reason a marriage divide in America has opened up.

In the 1960s, almost all prime-age men with a high school diploma were working, but, nowadays, that number drops to just 85%. And between 1973 and 2015, real hourly earnings for this group have fallen by 18%, as we note in our new report.

We propose two solutions to make young men more marriageable. First, we can better equip those who seem set to start out on low-income, low-skilled jobs by improving vocational training. Our high schools and community colleges need to do more, not only to beef up vocational programs that prepare young adults for local jobs, but also to raise the status of vocational education in the eyes of students and community members.

Secondly, we can make work more appealing by introducing a wage subsidy, perhaps by switching the earned income tax credit into an hourly top-up to wages. This would give young men (and women)—in particular, those with low education—greater encouragement to work full time and make them more attractive candidates for marriage.

We’re thinking here of the way in which the U.S. military has increased the rate of marriage among its ranks, many of whom are from working-class backgrounds. What’s also interesting is the research suggests there is virtually no racial gap in marriage in the military. Whites and Blacks marry at about the same rate. What’s the military’s secret? It provides great benefits and doesn’t give them to cohabiting couples. In other words, it privileges marriage. The rest of the government should do likewise.

The alternative to taking policy steps like these is to accept a world where the United States is stuck in a separate-and-unequal family regime, where strong and stable families are the preserve of the privileged and powerful and everyone else is consigned to increasingly unstable, unhappy and unworkable families, or to no family at all. We think we can all agree that this alternative is unacceptable and un-American.

Brad Wilcox is director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and The Future of Freedom fellow at the Institute for Family Studies. Chris Bullivant is the director of the Social Capital Campaign. This article is adapted in part from the new report, “Family Stability — Bridging America’s Social Capital Divide,” which was published by the Social Capital Campaign.

Editor's Note: This article appeared first at the Deseret News. It is reprinted here with permission.