Highlights

- The potential scope of the eviction crisis is overwhelming, and it is having a disproportionate impact on families with children. Post This

- Many families with children were just making ends meet before the pandemic. The eviction moratorium may not improve their financial footing. Post This

- Families with children who rent are more than twice as likely to be headed by a single parent than families with children who own their homes (54% of renters versus 19% of owners). Post This

The coronavirus pandemic and the economic and social crises it has caused have gone on for longer than anyone could have imagined almost a year ago. Even with additional unemployment benefits and rental assistance for low-income households, many individuals and families are struggling to cover their housing payments while facing job losses and the need to care for school-aged children.

The pandemic has brought families with children closer to the edge of the financial cliff—but financial insecurity, especially a lack of affordable housing, predates COVID-19. Aid programs and short-term policies are keeping these families afloat for now, but the high cost of housing compared to what families earn has created a situation where this temporary assistance is their only safety net.

Many states and localities issued eviction moratoriums in the spring and summer of 2020 to prevent a wave of renters from facing eviction from what was thought to be a temporary setback. In September 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a national eviction moratorium that applies to most renters who have been financially burdened by COVID. However, the CDC moratorium is set to expire on March 31, as regions across the country slowly emerge from a second round of shutdowns. The CDC rule does not prevent landlords from initiating eviction proceedings or from demanding all back rent and fees when the moratorium expires. Many emergency rental assistance programs have run out of funding, and there is not enough funding to support everyone who qualifies for assistance.

As a result, local governments and communities are bracing for the impact of tens of thousands of families and children losing their housing. The potential scope of the eviction crisis is overwhelming, and it is having a disproportionate impact on families with children.

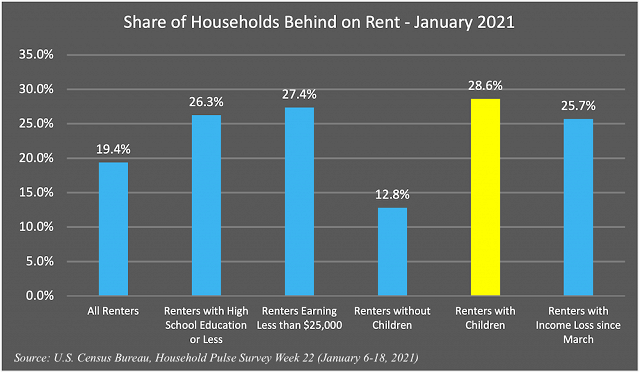

Nearly 20% of all renters were behind on their rent payments in January. Rent delinquencies were particularly high among families with children in the home. Nearly a third of renters with children were behind on rent payments—over double the rate of renters without children.

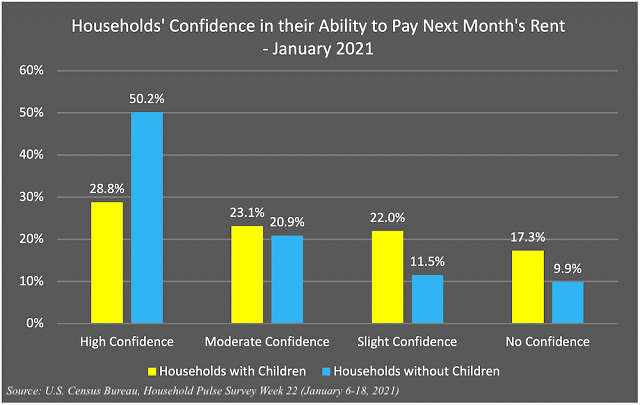

Moreover, about 40% of renter households with children had only slight confidence or no confidence at all that they would be able to pay the rent in full next month, while households without children face far less risk.

Why are renters with children falling behind on their rent at rates higher than economically-disadvantaged groups, such as renters with no college education and renters who have lost work during the pandemic? One possibility is that renters with children spend more on housing as a share of their income than renters without children, financially “stretching” into more expensive neighborhoods to give their kids better schools and safer streets. These families might be more likely to fall behind on rent when they lose income, compared to households with more “wiggle room” in their housing budgets.

Families with children might also be more likely than renters without children to stay in their current housing when they lose income in order to provide stability for their kids—and it’s probably a lot easier for a childless single to move back into their parents’ home than a family of four. Moreover, families with children who rent are more than twice as likely to be headed by a single parent than families with children who own their homes (54% of renters versus 19% of owners), which increases their financial precarity. Whatever the reasons, these families are racking up rental debts that put them at risk of eviction and will make it harder for them to find good rental housing in the future.

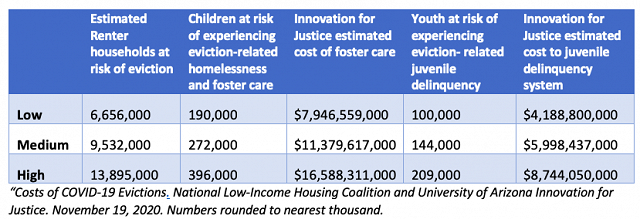

When families are evicted, many end up doubling up in friends’ and families’ homes, living in motels or in their cars—functionally homeless, even if they are not counted in the official federal statistics. Housing instability and homelessness are catastrophic for the well-being of families but also have costs to society. Among other consequences, families who lose their homes are at higher risk of becoming involved with the child welfare and juvenile delinquency systems. A recent report from the National Low-Income Housing Coalition estimates that the potential costs to local child welfare and juvenile delinquency systems from family evictions nationwide range between $12 billion and $25 billion.

To prevent the pandemic crisis from becoming a housing and homelessness crisis, housing policymakers are prioritizing assistance to keep people from getting evicted. After a protracted game of chicken, Congress finally passed an additional COVID-19 economic relief bill that provided an additional $25 billion to states and local governments to make emergency rental assistance available. Renters can use the aid to pay for back rent as well as current rent (and utilities). One of President Biden’s first executive orders extended the CDC eviction moratorium to March 31, 2021. Many states and localities have their own eviction moratoria, which extend beyond the end of March—and President Biden has signaled his interest in extending the federal moratorium to September 2021.

The goal of these measures is to keep families afloat until the economy recovers. However, many families with children were just making ends meet before the pandemic. The eviction moratorium may not improve their financial footing—they may owe so much back rent when the moratorium expires that they can’t catch up. Moreover, landlords—even those who were able to delay payments on federally-backed mortgages due to COVID-related forbearance—may rethink their choice to rent to a lower-income family after not receiving rent for over a year. This potential consequence only worsens the underlying problem, which is a lack of affordable housing for lower-income families.

Insufficient affordable housing, especially for families, is the big problem that needs to be addressed. Providing rental assistance and housing vouchers are short-term solutions. In the long term, cities and towns must embrace policies that enable affordable housing to be built, such as relaxing zoning rules, reducing permitting and impact fees, and shortening the planning timeline for development. By increasing the supply of affordable housing, we can help more families move back from the financial cliff.

Claudia Sharygin is an economist and data scientist specializing in program evaluation and housing and urban policy. Most recently, she has worked on data-informed program design and implementation for housing-related COVID emergency funding.