Highlights

- The prevalence of emotional disorders has clearly increased among adolescents in the first two decades of the 21st century. Post This

- The Lancet study confirms that adolescents today across multiple parts of the world experience earlier onset & a prolonged period of heightened emotional problems than those born previously. Post This

- Girls are far more likely than boys to be “liked” or “disliked” based on their looks, and girls learn quickly that the more clothes they take off, the more “likes” they get. Post This

The remarkable social reformer, Jane Addams, once said, “We all know that each generation has its own test, the current standard by which alone it can adequately judge of its own moral achievements.” In these moments, she added, “to pride one’s self on the results of personal effort when the time demands social adjustment, is utterly to fail to apprehend the situation.”

Recent research released in the prestigious journal, Lancet, sheds light on what is certainly one, if not the greatest, test facing this generation: the crisis in adolescent mental health. Like those Addams spoke of, this test demands social adjustment. The question is whether we will apprehend and respond in a way that meets the challenge before us.

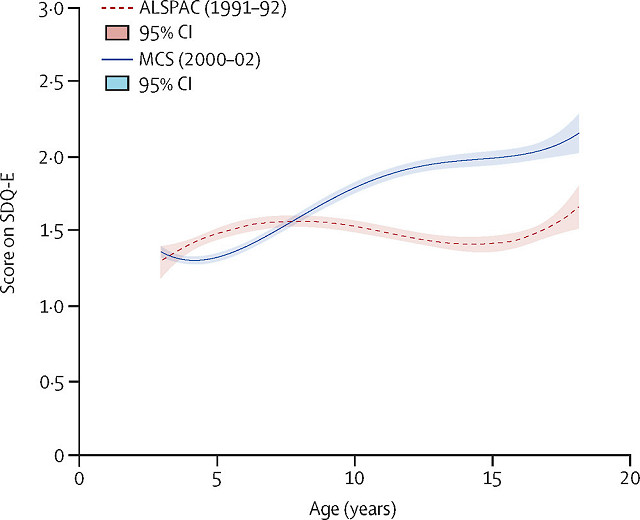

Drawing on data from 20,000 adolescents in the United Kingdom representing two generational cohorts (the first born in 1991-1992, the second born in 2000-2002), researchers used parent reports to explore whether age at onset and extent of emotional problems has changed for adolescents across generations. The prevalence of emotional disorders and symptoms has clearly increased among adolescents in the first two decades of the 21st century. Whether and how generations have changed, however, has been less clear.

In fact, the study confirmed a significant generational shift. The later cohort of adolescents assessed from 2000-2002 had an earlier onset of problems with steeper and sustained higher average trajectories of emotional problems compared to the earlier cohort. This was particularly true for adolescent girls. While both cohorts of adolescent girls showed increasing emotional problems during adolescence, those born in 2000-2002 had particularly high emotional problem scores that began earlier and lasted for longer than the earlier cohort. Though not as high as the girls, adolescent boys born in the later cohort also had higher parent-rated emotional problem scores, with an earlier and more sustained increase in problems than the earlier cohort.

Figure 1. Average population trajectories of emotional problems in the ALSPAC

and MCS cohorts by age

Of course, the findings are not unexpected. Earlier this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention touched off a national conversation when it reported that almost 60% of teen girls in the U.S. reported feeling “persistently sad or hopeless” and that 30% had seriously considered attempting suicide. This finding came on the heels of research from Harvard’s Human Flourishing Program, which found that after decades of higher reported well-being, young adult well-being has dramatically declined compared to older age groups—with young adults being less happy, less healthy, less financially stable, experiencing less meaning, having greater struggles with character, and poorer relationships than young adults in the past. As author Tyler Vanderweele concluded, “Relatively speaking, young people are not doing as well as they once were.”

What the Lancet research study confirms is that adolescent girls and boys today across multiple parts of the world experience earlier onset and a prolonged period of heightened emotional problems than those born previously. The developmental course of emotional problems has, in fact, changed between generations, with the greatest emotional risk for girls. And it’s not showing up in childhood; it’s an adolescent issue. The substantial and increasing differences only appear from age 11 and on.

The question, of course, is why is it happening, and what do we do? As the Lancet authors note, numerous interconnected changes including changes in family life, social and educational environments, use of digital tools for learning and socialization, society’s expectations, and how young people perceive themselves have meant significant changes in young people’s lives relative to past generations. What does appear to be clear is that these interconnected changes are making the critical neurodevelopmental transition of adolescence far more psychologically challenging, especially for girls. Surely, an appropriate social adjustment means accurately apprehending some of these interconnected changes.

More than 15 years ago, the American Psychological Association (APA) released its landmark analysis of the rampant sexualization of women. In “study after study,” they found women portrayed in a sexual manner and objectified (e.g., used as a decorative object, or as body parts rather than a whole person) with a “narrow (and unrealistic) standard of physical beauty highly emphasized.” The effects on women were profound: negative emotions, like shame, anxiety, and even self-disgust were strongly associated with this objectification. Focusing on their bodies while comparing themselves to narrow ideals was associated with “disrupted mental capacity.” Disordered eating, low self-esteem, and depression were also linked to exposure to sexualized ideals. And consuming sexualizing messages was repeatedly linked to diminished sexual health, sexual stereotyping, and distorted conceptions of femininity.

But this was before social media became ubiquitous, and the sexualization of girls and women was put on steroids. As award-winning journalist Donna Nakazaw notes in Girls on the Brink, today girls’ innate sensitivity to their environment has to develop within a heightened culture of performance, comparison, and judgment. Girls are far more likely than boys to be “liked” or “disliked” based on their looks, and girls learn quickly that the more clothes they take off, the more “likes” they will get.

In such a world, as New York Times writer Michelle Goldberg insightfully describes, girls are “constantly packaging themselves for public consumption and seeing their popularity and the popularity of others quantified.” Such a developmental context cannot help but exacerbate the normal insecurities of adolescence, a period in which “both fashioning the self and finding a place to belong are paramount.” One has to ask how any adolescent can traverse this critical and sensitive identity-forming developmental period when, in Freddie DeBoer’s poignant words, social media creates “a sense of another consciousness that’s welded to your own consciousness and has its own say all the time.”

Undoubtedly, this interconnection is only one part of the biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors that are negatively shaping adolescent development today. But it is one that demands the social adjustment Jane Addams spoke of if we are to rise to meet the great test of our day, for ourselves and for the vulnerable young for whom we are responsible. That is why all of our efforts—through policy, parent and youth education, and families–are necessary.